You can’t get $1 out of the bank in Venezuela. I tried.

Four hours. Four banks. Six cents.

Four hours. Four banks. Six cents.

This was a typical day in Caracas, Venezuela, capital of the world’s most miserable economy.

In most of the world, getting a little money out of the bank is an errand, something forgettable. In Venezuela, for millions of people, it is complicated, tedious and surreal, or just impossible.

I moved here a year and a half ago to cover the country’s economic crisis as a freelance journalist. I knew how bad things were, but I never imagined the constant daily struggle to achieve even the simplest of tasks.

As Venezuela has sunk to new depths, prices have skyrocketed, and the currency, the bolivar, has become next to worthless. Supermarkets and banks have become scenes of confusion and chaos: Are they open? Do they have money or food? How much can I get?

Inflation is so rampant — some experts say it ran above 4,000% last year — that it has devoured people’s salaries.

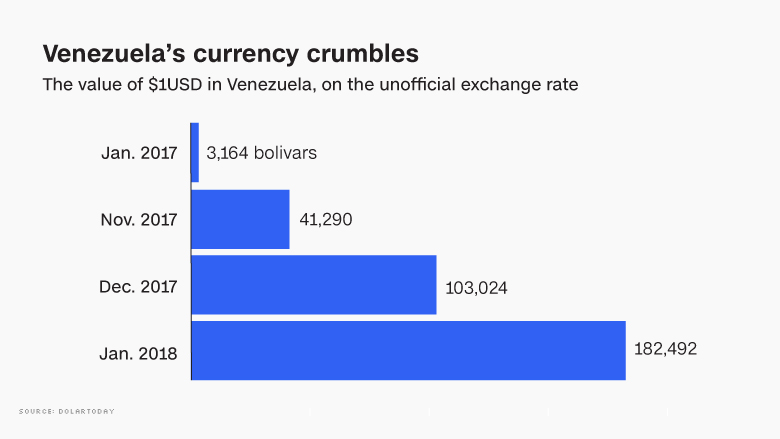

As I write this, one dollar fetches about 191,000 bolivars, according to the black market exchange rate that everyone uses. (Nobody trusts the overvalued official rate because the government has lost credibility among ordinary Venezuelans and in international markets that determine exchange rates.)

A year ago, one dollar fetched 3,100 bolivars. The bolivar has lost 98% of its value since then. Even on the day I reported this story, January 11, a dollar would have gotten me about 151,000 bolivars in the morning.

Venezuela’s banking authority tells banks every month how much customers can withdraw at one time, according to an official statement. But the authority doesn’t make that amount public.

In August, Venezuelan media outlets reported that the authority set the limit at 10,000 bolivars per customer. Press officers declined to elaborate on the rules. The Bank Association of Venezuela, which represents bank branches, closed its press office six months ago.

As the currency loses value, the banks themselves have become their own scenes of confusion. Customers wait in long lines. Some banks don’t offer cash and allow only electronic transactions.

So how hard is it to get a dollar’s worth of bolivars?

I tried. And failed.

The first bank: ‘Minimum an hour’ wait

I got to my first bank at 9:30 a.m. Dozens of people were lining up in front. People wait for cash here like Americans queue up to buy lottery tickets when the jackpot soars.

Inside, the five ATMs were deserted, a sign that they were out of cash. The only option was to withdraw money with the bank teller. I quickly counted 21 people in line and just one teller working.

«It’s minimum an hour waiting,» the last man in line told me as I approached.

I decided to try my luck elsewhere.

This problem has exploded in recent months, but it developed over years.

Venezuela was once Latin America’s wealthiest nation, but it was plagued by extreme inequality. A socialist leader, Hugo Chavez, promised to fix the country’s deep disparity between rich and poor when he became president in 1999.

Chavez ramped up government spending, providing housing and services for millions of poor Venezuelans. But critics and economists said for years that the spending was irresponsible and unsustainable.

Chavez died in 2013, and his hand-picked successor, Nicolas Maduro, took over. Maduro maintained socialist policies, even while government coffers drained. Food shortages and electric blackouts became more common.

The country spiraled into economic and social unrest following a plunge in oil prices in 2014. Venezuela has more oil than any other nation on earth, but oil is the nation’s only source of revenue. Government mismanagement and widespread corruption have caused oil production to plummet.

To patch the inflation problem, the Venezuelan government has repeatedly increased the monthly minimum wage, but prices have risen faster, and the bolivar has plunged further. And it got worse over the holidays.

The second bank: ‘It’s nonsense!’

I walk a few blocks to a second bank. That I could find another one so quickly is a luxury of Caracas. In rural parts of Venezuela, cash is a necessity, and banks are far apart.

At the second bank, the ATMs were already out of cash, and it wasn’t even 10 a.m. Frustration set in. Only 10 people were waiting for the tellers, so I decided to line up.

Gustavo Vasquez stood next to me in line. He told me he only needed 30,000 bolivars, or about 18 cents, for a CLAP bag: a sack of food and toiletries the government gives out to the poorest Venezuelans each month at heavily subsidized prices.

Recently, CLAP bags have gotten smaller or been delayed as more Venezuelans slip into poverty and as the government runs out of money to import essential goods.

As one of the many who now rely on food handouts, Vasquez was not on benefits for most of his life. He used to have a full-time job and a quiet life on his pension. But inflation made it impossible for him to live off his income, and government programs like CLAP are now a lifeline for him and his family.

Critics argue that the CLAPs are used as a political weapon by Maduro to force people to vote for him. But the ethics of political aid were not on Vasquez’s mind. He just wanted to get cash so he could pay for the vital handout and eat.

«Here, they only allow [you] to take out 5,000 per day,» Vasquez told me. «What should I do? Open an account in six different banks? It’s nonsense!»

I managed to reach the front of the line, but the teller said I had to present a check to withdraw money. She wouldn’t let me use my debit card. Increasingly annoyed, I left the second bank and passed two others before surrendering and heading home to pick up my checkbook.

I waited four hours to get 6 cents. I spent it all in one place.

It was noon. I had been looking for cash for more than two hours. I returned to the first bank I tried.

I waited another hour in line before reaching the teller with my checkbook in hand. I noticed how everyone in line was still calm and silent, as if general resignation had forced these people to simply accept the situation.

Social rage exploded last year in Venezuela when hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets of Caracas for more than 90 days to protest changes to the constitution and to demand elections and humanitarian aid.

The protests were quashed by government forces. More than 120 people lost their lives, according to state-run media. Police fired rubber bullets and shot tear gas. Protesters lobbed Molotov cocktails. A gas mask became a daily requirement for my reporting.

Now it seems that the economic situation is so bad that the average Venezuelan is too busy scrambling for cash and food to take to the streets once again.

At 1:23 p.m., I finally presented my check and got the hard-earned cash: 10,000 bolivars, or 6 cents.

Yarmira de Motos, the teller, informed me that the bank manager establishes every morning how much each customer can withdraw based on how much money is delivered by the Venezuelan Central Bank.

For this reason, some banks may allow 5,000-, 10,000- or even 30,000-bolivar withdrawals depending on the day. It’s a total gamble.

With my 10,000 bolivars in hand four hours later, I met a friend for a coffee. My cappuccino cost 35,000 bolivars.