America´s Hispanics – Education: College or bust

Why schooling is critically important

Why schooling is critically important

SCHOOL BUSES IN Bernalillo, New Mexico, carry baby seats, and the high school recently opened an in-house creche. Ideally, town elders would prefer teenage students not to get pregnant in the first place. Alas, unplanned teen pregnancies are more common among Hispanics than in any other group in America. They are most prevalent in rural areas, and strongly associated with childhood poverty.

Small, drab Bernalillo is mostly Latino, poor and surrounded by mile upon mile of desert scrub. In the past three years a total of 39 teenagers have fallen pregnant while at high school, earning them a place in a programme, NM Grads, that helps students with babies complete their education. So far 14 have graduated. Dropping out is bad news in a town where without a diploma “you can’t even get a job in a fast-food restaurant,” says Rebecca Cost, a teacher who runs the NM Grads centre.

Motherhood can easily prove overwhelming for students. Most lack transport, so if they are late for the bus they miss school. Some have boyfriends at the school, who are offered fatherhood classes and prodded to help care for their baby. The programme offers support with schoolwork, lessons in child care, financial literacy classes and free birth control to forestall further pregnancies.

To date no student has chosen an abortion; very few local families would allow it, suggests Ms Cost. Yet traditional values stretch only so far. None of the mothers has married while at the school. After the initial shock, most families “very quickly” welcome the new child, Ms Cost reports. Monique Miramontes, an 18-year-old student with a new daughter, Jaylah, says her parents are not pushing her to marry her boyfriend. They were very disappointed when they first heard about her pregnancy, she concedes, “but as time went on, they got excited.”

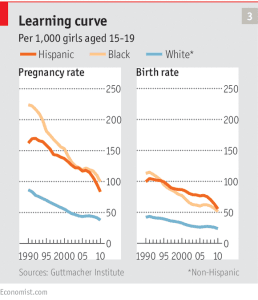

Pessimists see places like Bernalillo as symptomatic of the social ills that afflict young Hispanics—and there are certainly reasons for concern. One in five Hispanic girls gives birth while still a teenager, compared with one in six black and one in 11 white girls (see chart 3). As a group, Hispanics suffer the most from childhood obesity. Almost one in four of them fails to graduate from high school on time. A legacy of under-education plays a role. A substantial minority of young Latinos, notably Mexican-Americans, have parents who never finished school. The latest National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a nationwide test, found less than a quarter of young Hispanics proficient in 8th-grade reading or mathematics, compared with around half of all whites and Asians. Optimists point to improvements, helped by a growing array of well-targeted, commonsense programmes, as in Bernalillo. Hispanic teen birth rates have dropped sharply in recent years, narrowing the gap with other groups (though that may be partly due to the economic downturn; recessions typically cause birth rates to fall). For several years now Hispanic high-school drop-out rates have been falling and college enrolment rising.

Outsiders sharply disagree about how to close gaps faster. The left sees a community in need of extra resources and support. On the right, Hispanic youth’s woes are seen as an indictment of big-government liberalism. In the scornful phrase of one think-tanker, Heather Mac Donald of the Manhattan Institute, the “government social-services sector” has latched onto Hispanics as a “new client base”. Social conservatives want to hear more talk of right and wrong and more campaigns to promote marriage, not hand out free condoms and baby care. Nativists see Hispanic social ills as proof that this culture is alien to American values. They put their trust in border fences and laws to deny undocumented migrants access to jobs and public services—though the Supreme Court ruled in 1982 that all children have a right to attend public schools, regardless of their legal status.

Both pessimists and optimists should have more faith in young Hispanics themselves, who are driving positive changes. A Pew Research study found second- and third-generation Latino youngsters much more likely than their foreign-born peers to say that teen parenthood interfered with achieving life goals. A big reason why Ms Miramontes is in no rush to marry is that her parents want her to go to college first. She plans to study nursing. Her boyfriend has moved in with her family and is holding down a full-time job at a bank.

Most Latinos are enrolled in highly segregated schools, with few white classmates. That is regrettable, but it need not spell doom. A generation ago John Overton High School in Nashville was largely white and middle-class. Today it is Tennessee’s most diverse school, with 63 nationalities and 70% of students speaking a language other than English at home, crammed into old, overcrowded buildings. Despite that, this impressive school has an 82% graduation rate, just above the national average.

Critical mass

Nashville’s Hispanic population has grown 13-fold since 1990, and 28% of the school’s students are now Latino, with many undocumented parents, as well as Central Americans who arrived last year during a wave of child immigration. Each year 15 or 20 new teenage students must be taught from first principles because they are not literate in their native tongue. The school essentially had to re-learn how to teach. One pupil in four receives intensive support in English. All get free bus passes, because staff found that undocumented parents without driving licences were afraid of driving children to school.

Having papers can make a big difference to students’ prospects of getting a good education. Public universities typically offer subsidised “in-state” tuition to legal local residents. Rules vary, but at least 18 states offer in-state tuition rates to students regardless of immigration status: it is a crucial marker of whether states are grappling with their future competitiveness. Tennessee, a conservative spot, does not currently offer in-state tuition to all. Shuler Pelham, Overton’s principal, says that 15- or 16-year-old Latinos tell him they are quitting school to work with fathers or uncles, earning $10 an hour in the building trade. When he urges them to consider their future, “they say, ‘what for? I’m undocumented. I can’t go to college’.”

Guadalupe Camino, a 17-year-old from Mexico who was given temporary papers thanks to Barack Obama’s executive action in 2012, can legally look for a job. “My mom tells me I am going to college,” she adds. But she is scared it may be unaffordable. Hispanics take a lot of responsibility from a young age, from driving their families everywhere (because their parents have no licences) to translating. Guadalupe’s fellow-pupil Marisol Crescencil notes that Hispanic girls face extra hurdles. Not only does she work six hours a night at a restaurant, she says, but “my parents put a lot of pressure on me to take care of my three brothers.”

Alma Carrasco is American by birth, as are three of her four siblings. But after her father was pulled over for ignoring a stop sign, he was ordered to attend a driver’s education class, at which his immigration status was checked. Alma’s life unravelled. Her father was deported last year and her mother had to join him to make ends meet, taking her youngest children with her. Alma went to live with an aunt so that she could attend college. It is her chance to repay her family’s sacrifices. “Now my parents aren’t here, I’m pushing myself harder,” she says, face crumpling.

For some years, large inflows of foreigners prompted calls to “demagnetise” Tennessee. In 2008, at a peak of nativist panic, 65 anti-immigrant bills were proposed in the Tennessee state legislature. Hardliners enviously pointed to harsh laws in neighbouring states. Then, as Tennessee businesses heard grumbling about labour shortages elsewhere, the Nashville chamber of commerce backed more in-state tuition. “A lot of time was spent saying, let’s not make the mistakes of Alabama and Arizona and Georgia,” says the chamber’s president, Ralph Schulz.

Steven Dickerson, an anaesthetist and Republican state senator for Nashville, thinks there is a good chance that a bill giving undocumented students the same discounted “in-state” college fees as other Tennesseans will pass this year. “We’re going to make them producers,” the senator tells fellow-conservatives. Population growth seems to have reached a tipping point: when one pupil in four in a town is Hispanic, indifference is no longer an option.