What happens when the country with the world’s largest oil reserves becomes its latest failed state? As Venezuela’s government grows increasingly despotic, a crack-up is accelerating — and despite plenty of warning, the world remains unprepared for the consequences.

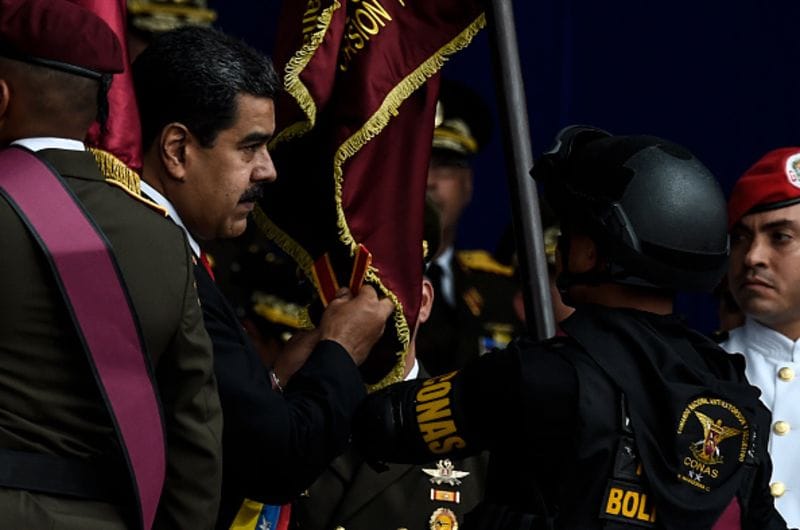

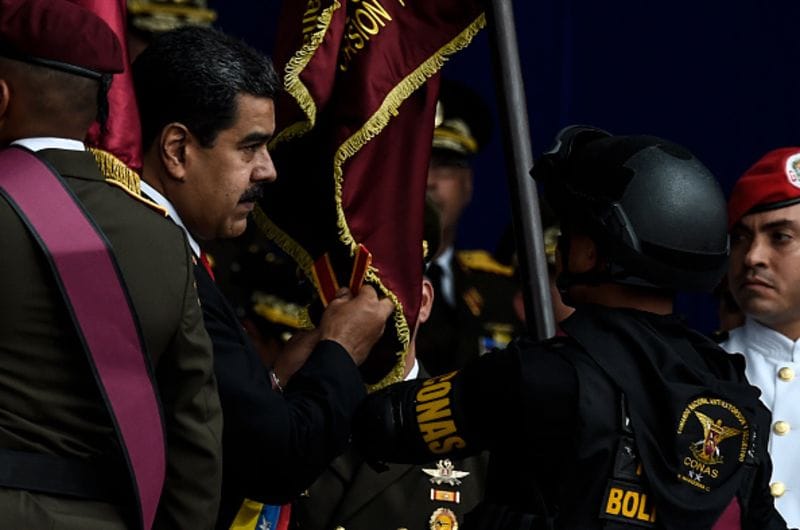

Recent headlines read like the plot of a Hollywood thriller: According to President Nicolas Maduro, assassins trained in Colombia tried to kill him with explosive-laden drones as he was delivering a televised speech. He has responded with a broad crackdown, including the jailing and alleged torture of one of his most vocal opponents.

Even as theories about the attack’s origins multiplied in Caracas, a judge in Delaware ruled that a Canadian mining company could seize the assets of Citgo Petroleum Corp.’s parent firm, a key piece of the beleaguered Venezuelan state-owned oil company that funds the government. The country was already in default on more than $4 billion in bonds. Its economy has shrunk by almost 50 percent since 2013. And hyperinflation that may hit 1 million percent this year is confounding everyday transactions — a crisis likely only to be aggravated by Maduro’s latest desperate gambit of a massive devaluation and lopping zeroes off Venezuela’s beleaguered bolivar.

Meanwhile, the humanitarian crisis spawned by repression of the population and mismanagement of the economy continues to spread. Food, medicine, electricity and even running water are in short supply — with the military increasingly in control of their distribution. More than 2 million Venezuelans have decamped to neighboring countries or to the U.S., where they have become the largest group of asylum seekers. Ecuador is scrambling to deal with the half-million Venezuelans who have entered this year.

And yet other countries have so far failed to forge an effective response. The U.S. and the European Union need to boost assistance to Brazil, Colombia and Ecuador, among others trying to deal with a refugee crisis that is nearing Syria-like proportions. Working with the International Monetary Fund, the world’s affluent countries also have to step up planning for an all-but-inevitable bailout and bond restructuring.

No such financial support can be offered, of course, until Venezuela has a government willing to restore democracy and pursue realistic economic policies. The U.S. and the EU should make clear to Maduro that using the drone incident as a pretext to lock up and abuse innocent opponents will trigger more asset freezes, travel bans and potential prosecutions by the International Criminal Court.

Yet there are limits to what sanctions can achieve, and dangers in applying them too bluntly. Moreover, new governments in Mexico and Spain are reluctant to pressure Maduro.

Incoming Mexican president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, for instance, favors a policy of nonintervention, which only ignores the danger at hand. China, for its part, continues to back the Maduro regime with loans-for-oil deals that at this point threaten to undermine China’s regional goodwill.

Maduro himself seems to hope he can stave off his country’s collapse with a mixture of economic fiats and iron-handed political control. He can’t. But a violent overthrow of his government would risk worse outcomes — civil war, for instance, or military dictatorship. Continued peaceful opposition, backed by international pressure and robust humanitarian relief, remains the best course.

The rest of the world needs to do all it can to help steer Venezuela to a better future and, at the same time, prepare for the economic and humanitarian crisis it may be unable to prevent.