Can This Man Oust Netanyahu?

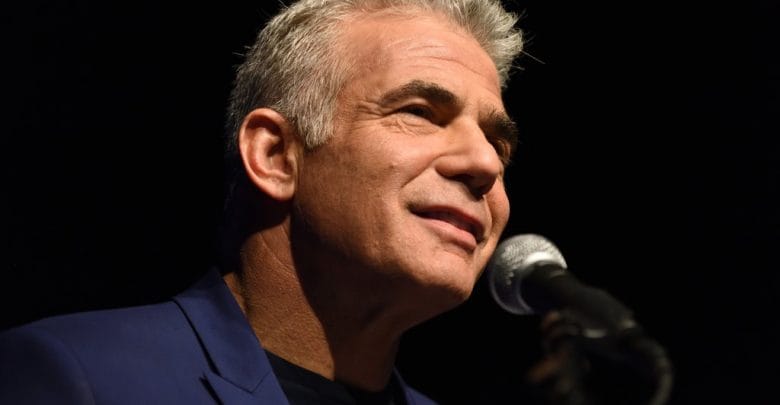

Yair Lapid, Israel’s consummate centrist, explains why his party can unseat Israel’s prime minister.

TEL AVIV — Imagine if Joe Biden and Colin Powell announced that they were setting aside partisan politicsand forming a new centrist party to save the country from Donald Trump. Then imagine that they were so serious about their goal that they promised to share power, rotating the roles of president and secretary of state.

Could they win?

That is the question Israeli voters are asking themselves. Last month, Benny Gantz, a former chief of staff of the army and a political rookie, and Yair Lapid, a former journalist and finance minister, came together to form Blue and White. (Mr. Gantz would serve as prime minister first, with Mr. Lapid as foreign minister.) The centrist party is named after the colors of the flag; its candidates are an all-star lineup of top military brass; and polls so far have put Blue and White neck and neck with Benjamin Netanyahu’s ruling Likud.

Over a week, I met many voters who say they will cast their ballot on April 9 for the centrists. Why? To a person, the answer boiled down to two words: Not Bibi.

I met Mr. Lapid on Thursday evening for tea at a North Tel Aviv cafe. When I ran this anyone-but-Bibi read of the election past him, he shot back that it was “dead wrong.”

In the hour that followed, Mr. Lapid, who calls himself a barometer of the Israeli center, made his case to me.

Voters are turning to his party because they are looking for basic morality, he said. While the sitting prime minister faces three charges of corruption, the men of Blue and White (the top eight of the 10 politicians on the list are men) are motivated by “old-fashioned, duty calls politics.” While Mr. Netanyahu’s message is one of division, Blue and White speaks about unity. And while Bibi has forged an alliance with the explicitly anti-Arab party Otzma Yehudit, Mr. Lapid said that a “racist” party “cannot be a part of a government in this country.”

The second difference between the men of Blue and White and Bibi, said Mr. Lapid, is how they see the role of Israel in a world in which democracy is on the decline. While Bibi has aligned himself with right-wing populists like Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil and Viktor Orban of Hungary, Mr. Lapid sees common cause with liberals like France’s Emmanuel Macron and Mark Rutte of the Netherlands. He hopes such politicians represent “a comeback of civil, moderate” leaders who understand “the risks and hazards of populism.”

A billboard in Ramat Gan showing the Blue and White leaders Moshe Yaalon, Benny Gantz, Yair Lapid and Gabi Ashkenazi alongside a billboard showing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu flanked by the extreme-right politicians Itamar Ben Gvir, Bezalel Smotrich and Michael Ben Ari. Credit Ack Guez/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Chief among those hazards is anti-Semitism.

Mr. Lapid said he is “very upset” by what he sees happening in Hungary — the country where his father survived the Nazi genocide. Given his concern with Mr. Orban’s historical revisionism, the way the autocrat has demonized the Jewish philanthropist George Soros, and his general xenophobia, what does Mr. Lapid make of the fact that Israel’s current government has cozied up to the Hungarian leader?

“A country as small as Israel, facing our magnitude of threats, cannot be that picky about the way other countries decide to govern themselves,” he began. But, he added, “we also have a moral duty. I pushed forward in the last Knesset a recognition of the Armenian Holocaust even though this is not the right practical move opposite the Turks. Because there is a point where you say enough is enough.”

He was far more careful when I turned to the subject of Donald Trump. “I am, like any other Israeli, thankful for President Trump. I sat at the opening of the Embassy in Jerusalem with tears in my eyes,” he said.

What of Mr. Trump’s recent flurry of statements about how the Democratic Party has become anti-Israel and anti-Jewish? “I’m going to say this as politely as I can,” Mr. Lapid said. “He was wrong. I don’t think you can say that Eliot Engel and Jerry Nadler and Ted Deutch and Chuck Schumer don’t like Israel. They are the most pro-Israel people I know.” Mr. Lapid said one of his priorities if he wins would be to rebuild support for Israel among progressives. “Israel must be a bipartisan issue,” he said.

One of the casualties of Israel becoming an increasingly partisan issue has been American Jews themselves, who vote overwhelmingly Democratic and who see Israel’s rightward turn as betraying fundamental liberal values. In other words, American Jews find themselves stuck between B.D.S. — the boycott movement against Israel — and Bibi.

“I understand the fact that some kind of gap was opened between Israel and the diaspora,” Mr. Lapid said of this problem. “I think what unites us — culturally, morally — is way bigger than what separates us. And what we need to go back to is this vocabulary of one people.”

It is when Mr. Lapid talks about Jewish values and Jewish history that he is the most compelling. Doubly so when it comes to the subject of his father, Tommy Lapid, a Holocaust survivor who built a life in Israel as a journalist and then as a politician, and died in 2008.

“My father had a friend in the Budapest ghetto. His name was Thomas Lantos,” Mr. Lapid said. “After the Holocaust, they went to the same pier in the same harbor and Tom took a boat and went left and my dad took a boat and went right.” Mr. Lantos eventually ended up in California, where he became a Democratic member of the House of Representatives and head of the Foreign Affairs Committee. “They always felt that if they took the opposite boat, Tom would be the minister of justice and my father would be the head of the foreign committee.”

“We are the revolving door,” he said, an unusual but beautiful metaphor for Jews’ shared sense of history and destiny. “I was once a young journalist in this country. I could have been you and you could have been me. We share something that we don’t totally have the words for. This is what the anti-Semites hate. We have something they don’t understand.”

Ultimately, though, what drives Israeli elections is not fine words about Jewish peoplehood, any more than it is marijuana legalization or tax policy. It is security.

Anyone who has paid any attention to the past two decades of headlines — the Second Intifada, Hamas’s rise in Gaza, the failed Arab Spring, the Syrian civil war — should understand Israelis’ sense of vulnerability in the region. Mr. Netanyahu’s long experience reassures many voters who still see Mr. Lapid as a former TV personality lacking in real substance and Mr. Gantz as a political novice.

Mr. Lapid is aware of this. “Security will be the first demand every Israeli in his right mind will talk to you about,” he told me.

“There are several issues in which the majority of Israelis — 70 to 80 percent — think approximately the same,” he said. “We are all students of the disengagement of 2005, in which Israel did what the world asked us to do. We left Gaza. We dismantled the settlements. And I supported it at the time. But you know what? It was a mistake, doing it unilaterally. The only thing that happened is that less than a year later they voted Hamas into power. We left them with 3,000 greenhousesfor them to build an economy and instead they built training camps” for jihadis.

So where does that leave the West Bank? Can the occupation go on indefinitely?

He paused. “It’s a very American question.” Because Americans think “everything is fixable.”

“Really, really wanting something or desiring something strongly is just not enough,” he said. “I’m not willing to see one Jew die because someone took an unnecessary risk in the name of values I really cherish. Like peace, like humanity, like people’s need for self-recognition.”

“We need to have the vision and the courage Menachem Begin had. But we also need to be very patient waiting for an Anwar Sadat on the other side. And there is no Sadat on the other side right now,” he says, referring to the Egyptian leader who made peace with Israel in 1979 — a cold peace that continues to this day.

In a way, this hawkish consensus is the story that Americans have missed about Israel. No serious contender for the prime ministership is talking about peace or an imminent two-state solution. Indeed, the fact that Mr. Lapid believes Blue and White can form “a unity coalition with post-Netanyahu Likud and Labor” shows just how far to the right Israel has shifted.

Two hours after I left Mr. Lapid, I heard the deep boom of the Iron Dome intercepting rockets over Tel Aviv. Back at the hotel, the receptionist showed me the bomb shelter, just in case. In the morning, I read that Israel had hit 100 targets in Gaza overnight.

“The Hamas rockets shot at Tel Aviv were a gift” to Bibi, a senior Israeli official, who asked for anonymity, told me the next day. “Netanyahu could fire back at a hundred Gazan targets without risking war. Hamas knows just how far it can push him, and he knows how far he can push back. The same cannot be said of Benny Gantz. If Blue and White is elected, he’s sure to be tested by Hamas and others, with untold consequences.”

Mr. Lapid thinks he and Mr. Gantz are more than up to the task.

“The Holocaust taught us that the only test of moral people is in immoral times,” he said. “This translates in Israel into daily dilemmas. You’re a young officer and someone is shooting at you and your soldiers from inside a hospital. What do you do? Who do you protect? How do you solve this problem? This tension between morality and survival is to me the core of 21st-century Judaism,” he said. “It is true in Pittsburgh. It is true in Tel Aviv. It is true everywhere. And I consider myself the keeper of this dilemma.”