The Economist: Vladimir Putin wants to forget the revolution

But ignoring its lessons is dangerous for Russia

But ignoring its lessons is dangerous for Russia

IN 1912 a group of Russian avant-garde poets, calling themselves futurists, published an almanac entitled “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste”. On its last page Velimir Khlebnikov, one of the authors, listed dates for the collapse of the great empires. The last line read: “Nekto [someone or somewhere], 1917”. “Do you believe that our empire will be destroyed in 1917?” asked Viktor Shklovsky, a literary critic, when he met Khlebnikov at a reading. Khlebnikov replied: “You are the first to understand me.”

“Nekto 1917” is the title of the main display at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution. It is one of the few public exhibitions in Russia about the two revolutions in 1917: the first in February, which overthrew the imperial government, and the second in October, which swept the Bolsheviks to power.

Central Moscow’s prosperity bears few traces of those violent events. An exit from the metro station in Revolutionary Square leads to a street lined with designer shops such as Tom Ford and Giorgio Armani. In nearby Red Square tourists and rich Russians sip $10 cappuccinos and gaze at the mausoleum shrouding the embalmed body of Lenin. It is almost as though the events of 100 years ago no longer matter.

In fact, over the past few years, they have taken on a new urgency. The Kremlin’s habitual use of history as a resource for shaping the present makes its reticence about the 1917 revolution all the more conspicuous. Its wariness is not a sign of historical distance, but of the potency of the revolution. It is today’s predicaments that make history relevant. Official silence about the revolution speaks volumes about the fears and discomforts of Russia’s elite today and about the hold on power of their president, Vladimir Putin.

Remember the revolution

That is why, despite being banished almost entirely from public spaces and official narratives, the centenary of the revolution nonetheless makes itself present in other ways throughout political life. On October 7th, Mr Putin’s 65th birthday, supporters of Alexei Navalny, the country’s leading opposition figure, marched in Mr Putin’s home city of St Petersburg, the cradle of the revolution. Invoking their president, the protesters chanted: “Down with the tsar!”

Russia today is hardly on the verge of a revolution. It is not involved in a ruinous war, as it was in 1917, and lacks the pent-up energy of that time. Its elites are more consolidated around Mr Putin than they were around Nicholas II—at least for now.

Yet the outward calm is deceptive. The kind of rule Mr Putin has gradually fashioned over his years in power has more in common with a tsar than with a Soviet politburo chief, let alone a democratically elected leader. The elites lack a legitimacy of their own and make no long-term plans. Everyone knows how easily tensions can flare up. Pollsters are registering a rise in social tension.

In the minds of Russia’s elites, revolution is mainly associated with the recent uprising in Ukraine. But perhaps another reason Mr Putin is so reluctant to recall the overthrow of the ancien régime is because he has modelled himself on its rulers. Instead the Kremlin is said to be preparing a display of mourning for the execution of the last tsar.

Mr Putin’s emergence as a 21st-century tsar is not as odd as it seems. Andrei Zorin, a historian at Oxford University, points out that the legitimacy of the tsar lies not (or, at least, not entirely) in the bloodline or the throne itself, but in the person who occupies the role and his ability to turn defeat into victory.

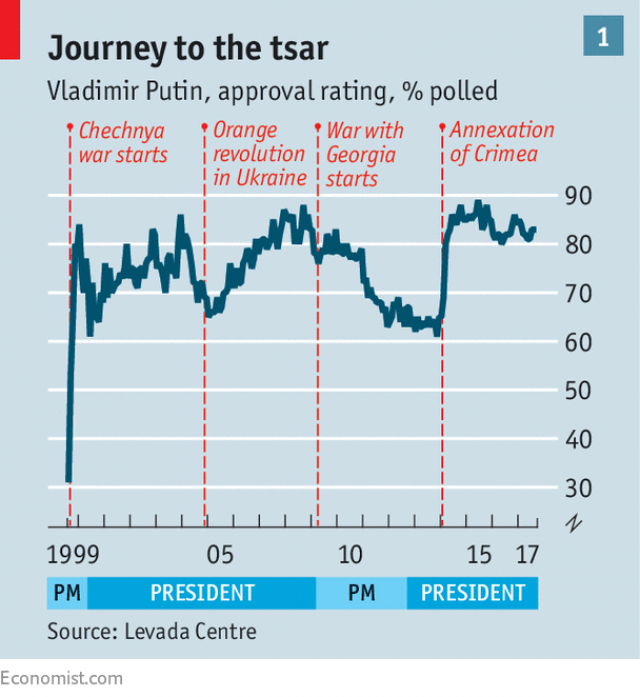

The event that gave Mr Putin’s legitimacy was the war in Chechnya in 1999. After the bombing of apartment blocks in Moscow and other cities, blamed on Chechen rebels, people latched onto him, then prime minister and Boris Yeltsin’s anointed successor, as their saviour. The day he appeared at the site of the bombing in Moscow, the public first registered and recognised him as their leader.

Like any tsar, Mr Putin has presented himself as a gatherer of Russian lands and the man who came to consolidate and save Russia from disintegration after a period of chaos and disorder. To create this image, he portrayed the 1990s not as a period of transition towards Western-style democracy and free markets, but as a modern instance of the Times of Troubles—a period of uprisings, invasions and famine in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, between the death of the last Rurikid tsar and the consolidation of the Romanovs.

In a manifesto entitled “Russia on the Threshold of the New Millennium”, published on December 29th 1999, two days before Mr Yeltsin handed him the reins of power, Mr Putin proclaimed the supremacy of gosudarstvo. Formally translated as “state”, the word derives from gosudar, an old word which signifies a monarch or master. A modern state is a set of laws and formal rules. Gosudarstvo is an extension of the tsar as the ultimate source of order and authority.

Mr Putin’s former KGB colleagues swore their allegiance to him as though he were the tsar. In 2001 Nikolai Patrushev, then head of the FSB, the KGB’s successor, described his servicemen as a new aristocracy and men of the gosudar. In the years that followed, they promoted a class system bound by intermarriages, god-parentage and family ties. Many top managers in Russia’s state-owned firms in the oil and gas and banking industries are the children of Mr Putin’s close friends and former KGB colleagues. They perceived their sudden enrichment not as corruption but as an entitlement and a reward for loyal service.

Tsar quality

But the most important source of legitimacy for this neo-tsar was the display of “unity with his people”. Every year since 2001 Mr Putin has appeared before the nation, miraculously restoring people’s fortunes and disbursing favours over the heads of his bureaucrats. He established a direct line to the Russian people, using state television stations to project his message. In keeping with the tradition of Russian monarchs, he presented himself not as a politician driven by ambition but as a “galley slave” to his people. He rarely appeared with or talked about his wife. A tsar, says Mr Zorin, is wedded to the Russian people and nobody can stand between them.

This direct mandate allowed him to consolidate power, emasculating alternative political and economic forces, including oligarchs, the media, regional governors and political parties. Those who refused to submit to his authority were banished or jailed. Whatever the formal reasons for sending Mikhail Khodorkovsky to a Siberian jail, most Russians believed that he fell foul of Mr Putin and deserved his personal wrath. Few questioned the prerogative of the tsar to banish a rebellious underling.

In Mr Putin’s system the oligarchs prosper at the ruler’s pleasure. Equally, the only source of legitimacy for regional bosses is not the electoral will of the people but his appointment or approval.

Mr Putin justified the Kremlin’s monopoly over politics and the commanding heights of the economy by evoking the symbols of tsarist rule and appealing to cultural stereotypes says Lev Gudkov, a Russian sociologist. The beginning of his second term in 2004 was marked by an inauguration which closely resembled a coronation. Konstantin Ernst, head of Channel One, the main state television station, created a royal setting. All Mr Putin had to do was to walk into it.

“It was like sticking a head into a cut-out of a tsar,” says Mr Gudkov. The Kremlin guards were dressed in tsarist-era uniforms. Their horses were borrowed from a film studio, having appeared in a scene about the coronation of Alexander III. Mr Putin walked down to the Kremlin cathedrals to the sound of Mikhail Glinka’s “Glory to the Tsar” and was blessed by the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox church.

The legitimacy of a tsar, however, requires continual reaffirmation. Russian rulers, including Ivan the Terrible, have sometimes tested their authenticity by temporarily placing a fake tsar on the throne. Mr Putin repeated the experiment in 2008 when he withdrew from the presidency, putting a younger and doggedly loyal lawyer, Dmitry Medvedev, in his place. All the while, however, real power remained in the hands of Mr Putin, who assumed the job of prime minister. In 2012 Mr Putin came back to his throne.

That year sliding ratings, and protests in Moscow and several other large cities, forced him to reaffirm his status by traditional means—and he saw his chance by expanding Russia’s territory during the protests in Ukraine in 2013 (see chart 1). Just as war in Chechnya helped create him, so conquest in Crimea pushed his ratings up to 86%, giving him an almost mystical aura.

Understandably, revolutions make tsars uncomfortable. At the end of 2004, just as Ukraine’s Orange revolution began, Mr Putin expunged the celebration of the Bolshevik revolution from the Russian calendar, replacing it with a somewhat spurious anniversary: the chasing of the Poles out of Moscow during the Times of Troubles. While Yeltsin rejected the revolution because it was the foundation myth of the Communist regime which he had defeated, Mr Putin turned against it because it separated two periods of what he saw as a continuous Russian empire. He wanted to paper over a dramatic breaking point in the long line of Russian rulers that led ultimately to his own reign.

Empire building

Yet the past is not so easy to tame. The centenary of the October revolution dramatises today’s challenges. Dominic Lieven, a British historian, writes that Russia faced a crisis as it entered the 20th century. Its main element was the alienation of the urban educated class from a state which refused to grant it political representation. Convinced that only an autocracy could hold the empire together, Nicholas II tried to rule a growing and increasingly sophisticated society as though he were an 18th-century absolute monarch.

Economically, the country prospered. By 1914 it was one of the largest and fastest-growing economies in the world, accounting for 5.3% of global industrial production—more than Germany. It ranked between Spain and Italy in GDP per person. It produced Malevich and Kandinsky, Prokofiev and Rachmaninov. Politically, however, it remained backward.

Even after Nicholas II was forced to grant a constitution in 1905, right up until the first world war, Mr Lieven writes, Russian politics boiled down to the question of whether to move down what was seen as the Western path of political development towards civil rights and representative government. Liberal advisers told Nicholas II that unless Russia’s political system were reformed, the regime would not be able to ensure the allegiance of modern educated Russians, and would therefore be doomed. His reactionary ministers retorted that any version of a liberal democratic order would inevitably bring on social revolution.

Russia’s elite is immersed in discussions about the lessons of the Bolshevik revolution. Nationalists and some of the clergy, including Mr Putin’s confessor, Father Tikhon Shevkunov, claim that the Bolshevik revolution was brought about by a Western-sponsored intelligentsia, who betrayed their tsar. The opposite camp blames the stupidity of Nicholas II and the corruption of his court, which fed the sense of popular injustice.

The debate is as much about the present as it is about the past. The economic growth of the 2000s (see chart 2) has also produced a thriving urban middle class that is alienated from the Kremlin. The challenge of transforming Russia into a modern state is as acute today as it was 100 years ago. The issues of legitimacy and succession of power are once again central to Russian politics.

Might, not right

Mr Putin’s rule is an example of what Douglass North, an economist, called “a limited-access order”. This is a state where economic and political resources are made available not by the rule of law but by privileges granted from above. Politically, it rests on a system that predates and survives the Soviet period. As Henry Hale, an American political scientist, explains in a recent article, these informal networks and personal connections take precedence over formal rules and institutions. In the 1990s these networks jostled for influence; in the 2000s they were integrated into a single pyramid with Mr Putin at the top as the chief patron.

The weakness of property rights and the rule of law are not accidental shortcomings, but necessary elements of this personalised system. The legitimacy of ownership or office can be provided only by the patron. The patron-client relationship cannot be imposed on a society, but requires its consent, which in turn depends on the popularity of the chief patron. Kirill Rogov, a political analyst, argues that Mr Putin appears both as a defender of his people against a greedy and predatory elite, and the defender of the elite against a possible popular uprising.

Mr Putin’s legitimacy does not extend to his government, which is seen by 80% of the population as corrupt and self-serving. Legitimacy cannot be passed from the tsar to the next generation. That makes the question of succession the most crucial one for Russia’s future, and the one that weighs most heavily on the minds of the elite. As Fiona Hill, senior director at the National Security Council, said in a recent essay written before she joined the NSC, “The increased preponderance of power in the Kremlin has created greater risk for the Russian political system now than at any other juncture in recent history.”

There is little doubt that Mr Putin will be reaffirmed as Russia’s president after the election next spring. But his victory will only intensify the talk of what comes afterwards. The point of the election is not to provide an alternative to Mr Putin, but to prove that there is none. And yet it is not just a formality. Although the tsar is not accountable to any institution, he is sensitive to public opinion and ratings. These are closely watched by opportunistic elites.

It is this weakness that Mr Navalny, Mr Putin’s main challenger, is trying to exploit. He brought young people onto the streets this summer and has been campaigning ever since despite the Kremlin barring him from standing in elections on the grounds of a criminal conviction it had engineered.

Mr Navalny is not seeking to beat Mr Putin—for that he would need a fair election. He wants to deprive him of “miracle, mystery and authority”. The Grand Inquisitor in “The Brothers Karamazov”, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s masterpiece, identified these as “the three powers, three unique forces upon earth, capable of conquering forever by charming the conscience of these weak rebels—men—for their own good.”

Mr Navalny first pierced Mr Putin’s aura in 2012 by branding his ruling United Russia party a collection of “crooks and thieves”. That description spread through the country, causing more damage to the Kremlin than actual revelations of corruption. Although Mr Navalny faces real physical threats, he shuns the image of a revolutionary, a crusader or a martyr, which only elevates the tsar; instead, he seeks to bring Mr Putin down to his level by portraying himself as a professional politician doing his job.

Recently he described Mr Putin not as a despot or tyrant, but as a turnip. “Putin’s notorious rating of 86% exists in a political vacuum,” he wrote in a blog. “If the only thing you have been fed all your life is turnip, you are likely to rate it as highly edible. We come to this vacuum with an obvious [message]: There are better things than turnips.” Laughter and mockery can erode legitimacy far more than any revelations.

What Mr Navalny offers is not just a change of personality at the top of the Kremlin, but a fundamentally different political order—a modern state. His American-style campaign, which includes frequent mentions of his family, breaks the cultural code which Mr Putin has evoked. His purpose, he says, is to alleviate the syndrome of “learned helplessness” and an entrenched belief that nothing can change.

Reordering Russia

The longer Mr Putin stays in power, the more likely his rule is to be followed by chaos, weakness and conflict. Even his supporters expect as much. Alexander Dugin, a nationalist ideologist, says Russia is entering a time of troubles. “Putin works for the present. He has no key to the future,” he says. While nobody knows what will follow, few people in Russia’s elite expect the succession to happen constitutionally or peacefully.

Writing in 1912, Russian artists could not imagine that Nekto 1917 would turn into a Bolshevik revolution. The Bolsheviks were a mere 10,000 people, and even in 1917 nobody could believe they would seize power, let alone hold on to it. Yet everyone sensed a crisis and corrosion at the heart of the Russian court. In February 1917, five days before the abdication of the tsar, Alexander Benois, a noted artist, wrote: “It seems everything may still blow over. On the other hand, it is obvious that the abscess has ripened and must burst…What bastards, or to be more precise, what idiots are those who brought the country and the monarchy to this crisis.”