Frankenstein cumple 200

Un afiche del «Frankenstein» de Mary Shelley, protagonizado por Boris Karloff, cuya caracterización del monstruo en 1931 creó la imagen arquetípica del monstruo. Crédito Universal Pictures.

La creación de Mary Shelley es una rara historia que pasa de la literatura al mito común, inspirando una corriente aparentemente interminable de adaptaciones.

En las ceremonias de entrega de premios de cine, la mayoría de los ganadores agradecen a sus estrellas, a sus agentes y a sus seres queridos. Guillermo del Toro, durante las palabras por su victoria a principios de este año con la película «La Forma del Agua», agradeció a una adolescente que llevaba más de 150 años muerta.

«Tantas veces, cuando quiero rendirme, cuando pienso en rendirme», dijo en el escenario de los Premios de la Academia Británica de Cine y Televisión en febrero, «Pienso en ella».

«Ella dio voz a los que no la tenían y presencia a los invisibles«, continuó, «y me mostró que a veces para hablar de monstruos, necesitamos fabricar los nuestros».

Del Toro, el principal creador de monstruos cinematográficos de nuestro tiempo, hablaba de Mary Shelley, la autora de «Frankenstein», y no por primera vez. Adaptar la novela -comenzada cuando Shelley tenía sólo 18 años- ha sido durante mucho tiempo un proyecto soñado por el director, que ha calificado la creación sin nombre de Victor Frankenstein como «el más bello y conmovedor» de todos los monstruos.

El mundo tendrá que esperar a la versión de Del Toro, pero este es el año de Frankenstein. El 200 aniversario de la novela ha inspirado una cabalgata de exposiciones, espectáculos y eventos en todo el mundo, desde Ingolstadt, la sede bávara del laboratorio ficticio de Victor Frankenstein, hasta Indiana, que en un intento por convertirse en el epicentro del frenesí estadounidense por Frankenstein, ha celebrado más de 600 eventos desde enero.

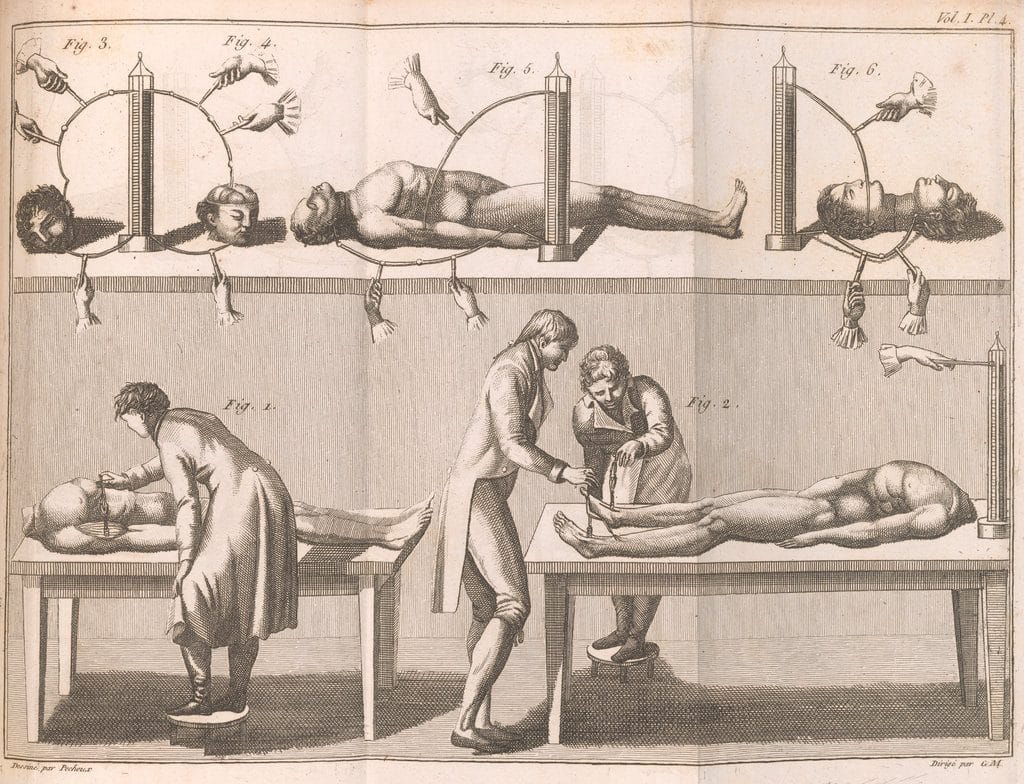

Aunque la novela es vaga acerca de cómo Victor Frankenstein da vida a su monstruo, Mary Shelley estaba familiarizada con los experimentos de «electricidad animal» de Luigi Galvani y su sobrino Giovanni Aldini, que se muestran aquí en un grabado de 1804. Crédito The Morgan Library & Museum

«Frankenstein» fue publicado anónimamente en 1818. En la edición de 1831, que llevaba su nombre, Mary Shelley incluyó un prefacio que describía el proceso que dio origen a «mi horrible progenie», como ella llamaba al libro. Crédito The Morgan Library & Museum

Pero, ¿cuándo no es el momento del monstruo? Aunque Frankenstein puede haber frustrado el deseo de su criatura de procrear, la novela de Shelley ha dado a luz una corriente aparentemente interminable de adaptaciones, incluyendo al menos 170 homenajes en pantalla, desde lo sublime hasta lo ridículo y más allá (ver «Alvin y las ardillas conocen a Frankenstein»).

Ha habido Frankensteins extravagantes, Frankensteins feministas, Frankensteins homosexuales, y Frankensteins políticos de todas las calañas, que han tomado la rebelión asesina del monstruo contra su fabricante como alegoría de todo, desde los excesos de la ciencia hasta el capitalismo, el racismo y la guerra.

Por supuesto, el zombi y el vampiro, recientemente de moda, que tienden a viajar en manadas, han protagonizado muchas alegorías propias. Pero no pueden igualar la profunda sacudida del reconocimiento humano que despierta el solitario monstruo de Shelley.

«La historia toca la parte más básica de lo que significa ser una criatura humana encarnada«, afirma Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger, co-curadora de «¡Está Vivo! Frankenstein cumple 200«, una exposición en la Morgan Library & Museum de Manhattan que reúne artefactos que van desde páginas originales del manuscrito hasta la colmena de Elsa Lanchester en «La novia de Frankenstein». «Nos deja preguntándonos, ¿soy un monstruo también?«

«Frankenstein» nació durante un verano famoso y sombrío de 1816, que se ha vuelto casi tan mítico como la historia misma. Mary Shelley y Percy Shelley, su esposo, fueron invitados a una villa junto a un lago en Suiza, donde se reunieron con Lord Byron y otras personas. El grupo pasó los días de lluvia imaginando historias de fantasmas, en una especie de juego de salón competitivo.

Los primeros destellos del monstruo le llegaron a Mary Shelley una noche. «Con los ojos cerrados pero con una aguda visión mental», recordó, «vi al pálido estudiante de artes ignominiosas arrodillado junto a la cosa que había creado». Luego, ella resumiría sus intenciones (al menos) duales hacia su «horrible progenie», como ella llamaba al libro: «hablar de los misteriosos miedos de nuestra naturaleza, y despertar un emocionante horror.»

«Frankenstein, o el Prometeo Moderno» fue publicado anónimamente dos años más tarde, en 1818, y casi inmediatamente se apoderó de la imaginación popular. Desde entonces, se ha convertido en la rara historia que ha pasado de la literatura al mito común.

Incluso las personas que nunca han leído la novela conocen la historia de la criatura deforme formada con partes de cadáveres humanos que se vuelve contra su creador, o al menos la imagen arquetípica de piel verde y tornillo en el cuello encarnada por Boris Karloff. (Esas características fundamentales están incluidas en los derechos de autor de Universal Pictures hasta el 2026).

El monstruo de Shelley era voluble y filosófico, pero perdió su elocuencia en la transición al escenario teatral, donde fue interpretado por el famoso actor especialista en pantomimas T.P. Cooke, que se muestra aquí. Créditos de la Biblioteca Pública de Nueva York

Pero casi desde el principio, también traspasó los límites de su propia novelista-creadora, abandonando algunas de sus propias características, empezando por la mayoría de las preocupaciones filosóficas del monstruo, e incluso sus capacidades básicas de expresión.

En la primera producción escénica, en 1823, la criatura sin nombre (o «—«, como se le identificaba en un programa teatral impreso que se muestra en la exposición de Morgan) fue interpretada por T.P. Cooke, un actor famoso por sus pantomimas,…. sentando las bases para un monstruo inarticulado, carente casi totalmente de palabras.

Si bien fue necesario el medio cinematográfico para avivar la tradición cultural pop de Frankenstein, también fue necesario el siglo XX para activar plenamente la advertencia contra el desenfreno de la ciencia. En un ensayo de 1987, el biólogo Leonard Isaacs atribuyó a Shelley el haber escrito lo que podría haber sido «el primer mito futuro», que «estaba esperando que la actividad humana lo alcanzara».

Una línea del Dr. Frankenstein de la versión cinematográfica dirigida por James Whale en 1931 – «¡Ahora sé lo que se siente al ser Dios!» – fue un blanco frecuente de los censores locales, que lo veían como una blasfemia. La «Novia de Frankenstein» de Whale (1935), según las notas de la exposición de Morgan, tuvo el cuidado de condenar cualquier entusiasmo expresado hacia su labor impía.

Pero desde entonces, la arrogancia de «jugar a ser Dios» ha sido libremente invocada en los debates sobre la bomba atómica, la inteligencia artificial, la ingeniería genética, la nanotecnología y casi cualquier otra tecnología que amenace con rebasar a sus creadores humanos.

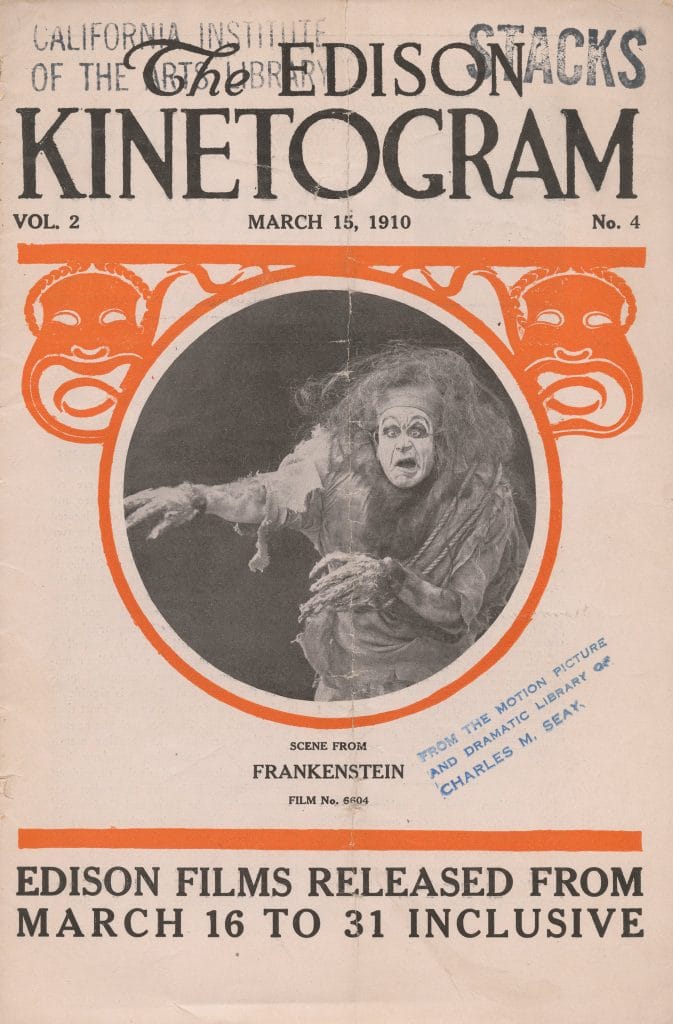

Se necesitó el cine para dar vida al arquetipo de Shelley, comenzando con la primera versión en pantalla, de Edison Studios, en 1910. Crédito California Institute of the Arts Library Special Collections

Para algunos, la propia metáfora de Frankenstein (con la ayuda de «Franken-comidas», «franken-ciencia» y otras aterradoras palabras con «franken«) se ha convertido en una especie de monstruo retórico, arrasando con la posibilidad de un debate público razonado sobre la innovación científica.

Ed Finn, un erudito literario de la Universidad Estatal de Arizona y co-editor de una nueva edición comentada de la novela de Shelley dirigida a científicos, ingenieros y «creadores de todo tipo«, afirmó que la historia de Frankenstein, cuando se invoca de manera simplista, es en sí misma una «narrativa peligrosa».

«Una mejor conversación sobre Frankenstein se centraría en la profunda conexión entre la creatividad científica y nuestra responsabilidad hacia nosotros mismos y hacia los demás«, dijo.

Pero si bien algunos esperan convertir la historia en una versión más positiva acerca de una ciencia ética, las artistas y críticas feministas la han leído como una alegoría de la usurpación masculina del poder procreador femenino.

La colección de poesía de Margaret Atwood de 1967 titulada «Discursos para el Dr. Frankenstein» imaginaba al monstruo como una mujer que se dirigía a su creador. En «Patchwork Girl» («La chica retazo») de Shelley Jackson (1997), una de las primeras novelas de hipertexto, la propia Mary Shelley crea el monstruo femenino, que luego se enamora de ella. (Para navegar, los lectores hacían clic en diferentes partes del cuerpo del monstruo.)

El monstruo (Joshua Jeremiah) ataca a su creador (Brian Cheney) en una escena de «Sketches From Frankenstein» («Bocetos de Frankenstein»), una nueva pieza de Gregg Kallor que se representó este mes en las catacumbas del Cementerio Green-Wood de Brooklyn. Crédito Joe Carrotta para The New York Times

Deidre Lynch, profesora de inglés en Harvard y profesora de un curso sobre monstruos, dijo que la novela trataba de la creación «antinatural» y también -tal vez de manera más convencional-, sobre la vida familiar.

«Por un lado, pregunta: «¿Y si odio a mi hijo?» y, por otro, «¿Y si mi padre me considera un inadaptado que ha fallado en parecerse a él?

La historia de Frankenstein se ha convertido en un referente para los artistas gays y transgéneros, que han extraído tanto su historia de rechazo paterno como su subtexto homoerótico (tal vez más literal en «Flesh for Frankenstein» de Andy Warhol). Algunos artistas transgéneros han tomado el miedo al cuerpo «antinatural» del monstruo y lo han puesto de cabeza.

En «Amateur: The True Story of What Makes a Man» («La verdadera historia de lo que hace a un hombre»), la reciente autobiografía del escritor Thomas Page McBee sobre cómo llegó a ser el primer hombre transgénero en luchar en el Madison Square Garden, se invoca a «Frankenstein» tanto como metáfora de la experiencia transexual como de la propia masculinidad, a la que él llama una especie de «monstruo creado».

«Para mí, la novela es una especie de referente poético que permite preguntar:’¿Cómo se convierte la gente en malvada? ¿Cómo puedo superar mis propios temores de convertirme en un monstruo?

Otros escritores han utilizado la historia para crear alegorías políticas del siglo XXI con doble filo. En «Frankenstein in Baghdad», del novelista iraquí Ahmed Saadawi, un vendedor ambulante sutura y une partes perdidas de las víctimas de los bombardeos con la esperanza de crear un cuerpo para un entierro adecuado, sólo para verlo convertido en un asesino desenfrenado.

«Destroyer» («Destructor»), una historieta reciente del novelista Victor LaValle que transporta la historia a la era de Black Lives Matter («Las vidas negras importan»), presenta dos «monstruos». Está el original de Shelley, que se encuentra vivo en el Ártico, y también un niño afroamericano de 12 años al que la policía dispara y luego su madre reanima; ella es una científica que resulta ser el último descendiente vivo de Victor Frankenstein.

LaValle, expresando su escepticismo acerca de «monstruos cursis», señaló que quería abrazar la ira de la criatura -y la de la madre-, considerándola «el derecho de los difamados y oprimidos».

Quizás, más simplemente, también quería llevar a los lectores a lo que le había atraído de Frankenstein en primer lugar.

«Cuando era niño,» dijo, «me sentí atraído por el miedo al monstruo. Quería un monstruo que partiera a un ser humano en dos, para bien o para mal».

Jennifer Schuessler es una periodista cultural que cubre la vida intelectual y el mundo de las ideas. Reside en Nueva York. @jennyschuessler

Traducción: Marcos Villasmil

NOTA ORIGINAL:

The New York Times

FRANKENSTEIN AT 200

Jennifer Schuessler

A cover for an edition of Mary Shelley’s «Frankenstein» featuring Boris Karloff, whose depiction of the monster in the 1931 film created the creature’s archetypal image. Credit Universal Pictures

Mary Shelley’s creation is the rare story to pass from literature into common myth, inspiring a seemingly endless stream of adaptations.

At movie awards ceremonies, most winners thank their stars, their agents, their significant others. Guillermo del Toro, during his victory lap earlier this year for “The Shape of Water,” thanked a teenager who had been dead for more than 150 years.

“So many times, when I want to give up, when I think about giving up,” he said onstage at the British Academy of Film and Television Awards in February, “I think of her.”

“She gave voice to the voiceless, and presence to the invisible,” he continued, “and showed me that sometimes to talk about monsters, we need to fabricate monsters of our own.”

Del Toro, the leading cinematic monster-maker of our time, was talking about Mary Shelley, the author of “Frankenstein,” and not for the first time. Adapting the novel — begun when Shelley was only 18 — has long been a dream project for the director, who has called Victor Frankenstein’s nameless creation “the most beautiful and moving” of all monsters.

The world will have to wait for del Toro’s version, but this is Frankenstein’s year. The novel’s 200th anniversary has inspired a cavalcade of exhibitions, performances and events around the world, from Ingolstadt, the Bavarian home of Victor Frankenstein’s fictional lab, to the hell mouth of Indiana, which in a bid to become the epicenter of American Franken-frenzy, has held more than 600 events since January.

While the novel is vague about just how Victor Frankenstein brings his monster alive, Mary Shelley was familiar with the «animal electricity» experiments of Luigi Galvani and his nephew Giovanni Aldini, shown here in an 1804 engraving. CreditT he Morgan Library & Museum

«Frankenstein» was published anonymously in 1818. In the 1831 edition, which carried her name, Mary Shelley included a preface describing the process that gave birth to «my hideous progeny,» as she called the book. Credit The Morgan Library & Museum

Then again, when is it not the monster’s moment? While Frankenstein may have thwarted his creature’s desire to procreate, Shelley’s novel has birthed a seemingly endless stream of adaptations and riffs, including at least 170 screen homages, from the sublime to the ridiculous and beyond (see “Alvin and the Chipmunks Meet Frankenstein”).

There have been camp Frankensteins, feminist Frankensteins, queer Frankensteins, and political Frankensteins of all stripes, which have taken the monster’s murderous revolt against its maker as allegory of everything from scientific overreach to capitalism to racism to war.

Of course, the recently fashionable zombie and vampire, who tend to travel in packs, have starred in plenty of pointed allegories of their own. But they can’t match the deeper jolt of human recognition that Shelley’s solitary, lonely monster stirs.

“The story touches on the most basic part of what it means to be an embodied human creature,” said Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger, a co-curator of “It’s Alive! Frankenstein at 200,” an exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum in Manhattan that gathers artifacts ranging from original pages of the manuscript to Elsa Lanchester’s “Bride of Frankenstein” beehive. “It leaves us asking, Am I a monster too?”

“Frankenstein” was born during a famously gloomy summer of 1816, which has become almost as mythic as the story itself. Mary Shelley and Percy Shelley, her husband, were guests at a lakeside villa in Switzerland with Lord Byron and others, who passed the rainy days dreaming up ghost stories, in a kind of competitive parlor game.

The first glimmerings of the monster came to her one night. “With shut eyes but acute mental vision,” she recalled, “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together.” Later, she would sum up her dual (at least) intentions of her “hideous progeny,” as she called the book: “to speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror.”

“Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus” was published anonymously two years later, in 1818, and almost immediately grabbed the popular imagination. Since then, it has become the rare story to pass from literature into common myth.

Even people who have never cracked the novel know the story of the misshapen creature patched together from human corpses who turns on his creator, or at least the archetypal green-skinned, bolt-in-the-neck image embodied by Boris Karloff. (Those key characteristics are under copyright by Universal Pictures until 2026, as it happens.)

Shelley’s monster was voluble and philosophical, but he lost his eloquence in the transition to the stage, where he was most famously played by the pantomime actor T.P. Cooke, shown here. Credit The New York Public Library

But almost from the beginning, it also slipped the bounds of its own novelist-creator, leaving some of its own patched-together parts behind, starting with most of the monster’s philosophical preoccupations, and even his basic powers of speech.

In the first stage production, in 1823, the nameless creature (or “——-,” as he was identified in a playbill included in the Morgan show) was played by T.P. Cooke, an actor famous for pantomime, . setting the template for an inarticulate, if not entirely wordless, monster.

If it took the medium of film to jolt the Frankenstein pop culture tradition alive, it also took the 20th century to fully activate its warning against science run amok. In a 1987 essay, the biologist Leonard Isaacs credited Shelley with writing what may have been “the first future myth,” which “lay waiting for human activity to catch up with it.”

A line of Dr. Frankenstein’s from James Whale’s 1931 movie version — “Now I know how it feels to be God!” — was a frequent target of local censors, who saw it as blasphemous. Whale’s “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935), the Morgan show notes, took care to condemn any enthusiasm he expressed for his unholy labors.

But since then, the hubris of “playing God” has been freely invoked in debates over the atomic bomb, artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, nanotechnology and just about any other technology that threatens to overrun its human creators.

It took the medium of film to jolt Shelley’s archetype fully alive, starting with the first screen version, from Edison Studios, in 1910. Credit California Institute of the Arts Library Special Collections

To some, the Frankenstein metaphor itself (aided by “Frankenfoods,” “frankenscience” and other scary “frankenwords”) has become something of a rhetorical monster, rampaging across the possibility of reasoned public debate about scientific innovation.

Ed Finn, a literary scholar at Arizona State University and co-editor of a new annotated edition of Shelley’s novel aimed at scientists, engineers and “creators of all kinds,” said that the Frankenstein story, when invoked simplistically, is itself a “dangerous narrative.”

“A better conversation about Frankenstein would focus on the deep connection between scientific creativity and our responsibility to ourselves and one another,” he said.

But if some hope to turn the story into a more positive one of ethical science, feminist artists and critics have read it as an allegory of male usurpation of female procreative power.

Margaret Atwood’s 1967 poetry collection “Speeches for Dr. Frankenstein” imagined the monster as a woman addressing her creator. In Shelley Jackson’s “Patchwork Girl” (1997), an early hypertext novel, Mary Shelley herself creates the female monster, who then falls in love with her. (To navigate, readers clicked on different parts of the monster’s body.)

The monster (Joshua Jeremiah) attacks his creator (Brian Cheney) in a scene from «Sketches From Frankenstein,» a new piece by Gregg Kallor that was performed this month in the catacombs at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Credit Joe Carrotta for The New York Times

Deidre Lynch, an English professor at Harvard who teaches a course on monsters, said the novel was about both “unnatural” creation, and also, perhaps more conventionally, about family life.

“It asks, on the one hand, ‘What if I hate my child?’ and on the other ‘What if my father deems me a misfit who has failed to resemble him?’,” she said.

The Frankenstein story has become a touchstone for gay and transgender artists, who have mined both its story of parental rejection and its homoerotic subtext (perhaps made most literal in Andy Warhol’s X-rated “Flesh for Frankenstein.”) Some transgender artists have taken the fear of the monster’s “unnatural” body and turned it on its head.

In “Amateur: The True Story of What Makes a Man,” his recent memoir of becoming the first transgender man to fight in Madison Square Garden, the writer Thomas Page McBee invokes “Frankenstein” both as a metaphor for the trans experience, and for masculinity itself, which he calls a kind of “created monster.”

“For me, the novel is a kind of poetic touchstone for asking, ‘How do people become evil? How do I work through my own fears of becoming a monster?’” he said.

Other writers have used the story to create double-edged 21st-century political allegories. In “Frankenstein in Baghdad,” by the Iraqi novelist Ahmed Saadawi, a peddler stitches together stray parts of bombing victims in hopes of creating a body for proper burial, only to see it become a rampaging killer.

“Destroyer,” a recent comic by the novelist Victor LaValle that transports the story to the age of Black Lives Matter, features two “monsters.” There’s Shelley’s original, who is found alive in the Arctic, and also a 12-year-old African-American boy who is shot by the police and then reanimated by his mother, a scientist who happens to be the last living descendant of Victor Frankenstein.

LaValle, expressing skepticism of “touchy-feely monsters,” said he wanted to embrace the creature’s — and the mother’s — rage, which he called “the right of the maligned and oppressed.”

Perhaps more simply, he also wanted to take readers back to what had drawn him to Frankenstein in the first place.

“As a kid,” he said, “I was drawn to the fear of the monster. I wanted a monster who would tear a human being in half, for better or for worse.”

Jennifer Schuessler is a culture reporter covering intellectual life and the world of ideas. She is based in New York. @jennyschuessler