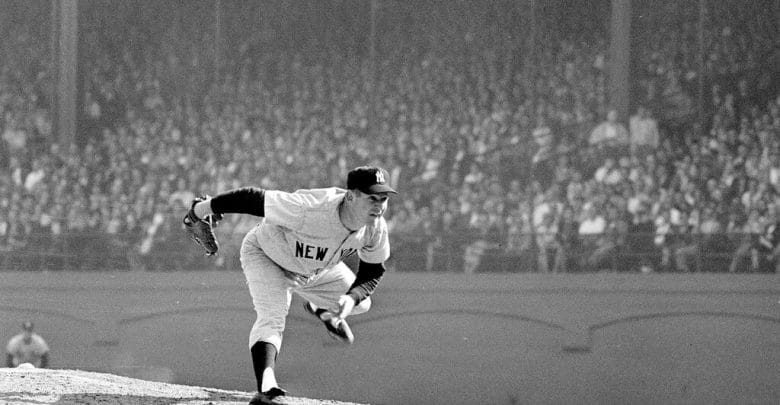

In a Golden Era for the Yankees, the Mound Belonged to Whitey Ford

Ford was a mainstay on a series of dominant teams in the 1950s and ’60s, collecting nearly every record for World Series longevity along the way.

Exactly 60 years before he died on Thursday night at age 91, Whitey Ford pitched a shutout in the World Series. It was the start of a scoreless streak that stretched 33⅔ innings, topping Babe Ruth for the longest in World Series history.

Yet Ford never believed he should have been pitching on Oct. 8, 1960, in Game 3 at Yankee Stadium against the Pittsburgh Pirates. At the time, Ford was a six-time All-Star on his way to becoming the team’s career leader in victories, with 236. He was the Yankees’ ace, and aces were supposed to start Games 1, 4 and 7.

Casey Stengel, who had managed Ford for a decade, had other plans. For the opener at the Pirates’ cozy Forbes Field, Stengel started Art Ditmar, a right-hander who had a strong season but who had never started in the World Series. Stengel wanted to save the left-handed Ford for the first game in Yankee Stadium, with its cavernous left-center field.

Ford would thrive in both locations, following up his Game 3 shutout in the Bronx with one in Pittsburgh while facing elimination in Game 6. But the latter effort left him unavailable for Game 7, when the Pirates scored off five Yankees pitchers in a 10-9 triumph. It was the last game Stengel ever managed for the Yankees, and he never lived down his decision.

“Whitey’s like Bob Gibson,” said Bobby Richardson, the Yankees’ second baseman at the time, by phone a few days ago, just after Gibson had died. “They were different pitchers, of course, but both of them were captains of the team, so to speak. They’re the ones you pitched against the tough opponents.

“Stengel’s excuse was it’s a small ballpark in Pittsburgh. But Whitey pitched his two shutouts, and had he been able to go three, I’m sure it would have been a different ballgame.”

The Pirates were just as puzzled as the Yankees players, but a lot happier to see Ford only twice.

“We wondered about it, and so did the players on the Yankee team — they couldn’t understand Stengel,” Pirates catcher Hal Smith, who hit a game-turning homer off Jim Coates in the finale, said in an interview shortly before his death in January. “He had a lot of talent on that club, but when it came to changing pitchers and things, he wasn’t too smart.”

Stengel was sharp enough to win seven titles in 10 tries, but in popular lore, it was the 1960 blunder that cost him his job — even though the Yankees were really just eager for a younger manager with less authority over personnel. Ford felt bad that Stengel was fired, according to his autobiography, “Slick,” written with Phil Pepe in 1987. But he fumed over the World Series slight.

“It was the only time I ever got mad at Casey,” Ford wrote, while insisting, like Richardson, that he would have won three starts if given the chance. “I was so annoyed at Stengel, I wouldn’t talk to him on the plane ride back to New York.”

Replacing the 70-year-old Stengel with Ralph Houk, who was 41, gave the Yankees’ dynasty a final, four-year burst atop the American League — and helped Ford to his best season.

Persuaded by a new pitching coach, Johnny Sain, Houk used Ford regularly on three days’ rest in 1961, instead of four or more, as Stengel had done. Ford responded with his best season: a 25-4 record and his only Cy Young Award.

The Yankees finished in first place again, and that time Ford did start the World Series opener, shutting out the Cincinnati Reds with a two-hitter. He added five scoreless innings to win Game 4 before leaving with a sore foot, and was named most valuable player after the Yankees prevailed in five games.

“This wasn’t exactly a new experience for me,” Ford wrote. “But it was the best. The end of an almost perfect year.”

Ford’s October magic soon ran out; he won the 1962 opener against the San Francisco Giants, but lost his last four World Series starts and never did pitch in a Game 7. He dabbled in trickery to survive in later years, throwing spitballs and mudballs. He also wore a custom-made ring to the mound, disguising it under a Band-Aid, and used a rasp to scuff the ball.

By then, though, Ford was so accomplished that umpires refused to embarrass him.

“There was one time when Whitey was scuffing up the ball and the umpire came out, and he knew,” Jim Bouton, a fellow Yankees pitcher in the 1960s who died last summer, said in an interview several years ago. “I forget who it was, but he was one of those old-timer guys who’s not going to be a wise guy or a big shot — this is Whitey Ford, he’s one of the greats. A certain amount of respect is due.

“So he went to the mound and the conversation went, ‘Uh, Whitey, I see the ring there. I tell you what, what you need to do is call time out and go in and change your jock strap. And when you come back, don’t have the ring on.’”

Ford revealed his methods in his book, published more than a decade after his election to the Hall of Fame for a towering career that spanned Yankees generations. In Ford’s debut in 1950, Joe DiMaggio played center field; in his final game, in 1967, Joe Pepitone played there. (Mickey Mantle was at first base.) On a staff in which most pitchers took brief star turns and went on their way — Don Larsen, Bob Turley, Ralph Terry, Bouton — Ford was the mainstay.

He holds nearly every World Series record for pitching longevity, and nobody else is close. Ford’s 22 starts are nine more than the total for Andy Pettitte, who ranks second. He worked 146 innings; Christy Mathewson would need five more complete games to top him.

Yet Ford’s won-lost record, like that of most aces, underscores just how hard it is, in any era, to win regularly in October. The Yankees won six World Series with Ford, but lost five others. His 2.71 World Series earned run average was almost identical to his regular-season mark (2.75), but his record was a modest 10-8.

There are exceptions — like Gibson, who was 7-2 in Series games — but many pitching greats have had similarly mixed postseason results. Mathewson was 5-5, Warren Spahn and Sandy Koufax 4-3, Steve Carlton 6-6, Tom Seaver 3-3. More recent masters have had similar luck: Tom Glavine, Randy Johnson, Greg Maddux and Mike Mussina had losing postseason records, Clayton Kershaw is 11-11, and Justin Verlander, while dominant in playoff rounds, is 0-6 in the World Series.

Likewise, controversial pitching decisions are nothing new. The Yankees said that Ford died at home, in Lake Success, N.Y., surrounded by family while watching his old team win a playoff game against the Tampa Bay Rays. Perhaps the Fords were also watching two nights earlier, when another Yankees manager, Aaron Boone, made a modern version of Stengel’s curious callby using an opener instead of a traditional starter in Game 2.

The Yankees lost that game, just as they lost Ditmar’s starts in 1960, but the pitching moves, of course, were only part of the reason. The Yankees probably still should have won Game 7 in Pittsburgh, and while Mantle cried in the dugout after Bill Mazeroski’s clinching homer — “He just felt like we had a better team and we had lost it, and he was just really sad,” Richardson said — few fans tend to shed tears for the Yankees. Their history is too rich to dwell on the sad parts.

So it is with the news of Ford’s death, which is less a cause for mourning than a chance to celebrate a career that included nearly everything a pitcher could want, even without an extra start in 1960.

Tyler Kepner has been national baseball writer since 2010. He joined The Times in 2000 and covered the Mets for two seasons, then covered the Yankees from 2002 to 2009. @TylerKepner