Jill Lepore: ¿Cómo acaban las historias de la peste?

En la literatura del contagio, cuando la sociedad está finalmente libre de la enfermedad, le corresponde a la humanidad decidir cómo empezar de nuevo.

El invierno pasado, cuando cayó por primera vez la pesadumbre, vi a una anciana, con la espalda doblada como un cayado de pastor, caminando atentamente a través de la lluvia helada. Atravesaba el aguanieve mientras cruzaba la carretera con botas negras que había forrado con bolsas de plástico para protegerse de la humedad y el frío. Llevaba una máscara de color carne, antinaturalmente lisa, pero esto era antes de que todo el mundo usara máscaras y, al principio, no pude saber qué era: parecía que no tenía nariz ni boca. Al acercarme, pude ver la cosa, hecha -debió de coserla ella misma- de un viejo sostén beige con aros, con una copa cortada y vuelta al revés, el cable sobre el puente de la nariz, los finos tirantes de nailon ceñidos a la parte posterior de la cabeza. Me acerqué a ella, pensando que debía decir algo: ¿se encontraba bien? Al instante, sus ojos se abrieron de par en par y se dio la vuelta, acelerando el paso. No volví a verla.

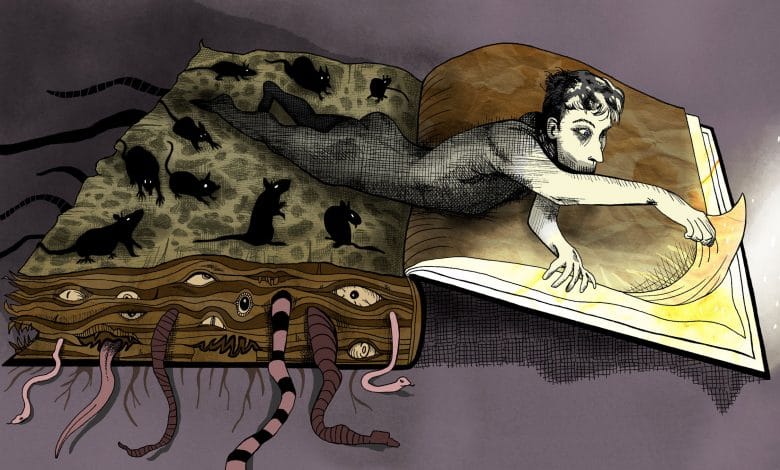

Poco después, empecé a escribir un ensayo sobre la literatura del contagio, historias sobre plagas. Durante el día, leía libros. Por la noche, cosía máscaras con retazos de tela y gomas elásticas, con toallas de papel dobladas por dentro como si fueran tampones. Me preguntaba cómo empezaban las historias de la peste y qué pasaba después. «Todo el mundo está patas arriba», dice un personaje de una historia. «Y ha estado patas arriba desde la llegada de peste». Los humanos pierden su humanidad, según la trama habitual. A medida que la peste se extiende, la gente se vuelve temerosa de los demás; las familias se encierran en sus casas. Las tiendas retiran sus mercancías; las escuelas cierran sus puertas. Los ricos huyen; los pobres enferman. Los hospitales se llenan. Las artes se marchitan. La sociedad desciende al caos, el gobierno a la anarquía. Finalmente, en la última etapa de esta aparentemente inevitable regresión, en la que la historia corre en sentido inverso, los libros e incluso el alfabeto se olvidan, el conocimiento se pierde y los humanos se convierten en bestias. En la novela de Octavia Butler de 1984, «El Arca de Clay», ambientada en el año 2021, los mutantes supervivientes de un patógeno alienígena de Próxima Centauri 2 «ya no son humanos».

Últimamente, a la espera de una vacuna, aguardo otro final. ¿Los humanos volverán a ser humanos?

Todas las plagas dejan su huella en el mundo: cruces en nuestros cementerios, manchas de tinta en nuestra imaginación. Edgar Allan Poe fue testigo de los estragos del cólera en Filadelfia, y es probable que conociera la historia de cómo, en París, en 1832, la enfermedad se cebó en un baile, en el que los rostros de los invitados, bajo sus máscaras, adquirieron un color azul violáceo. En el relato de Poe «La máscara de la muerte roja», de 1842, el príncipe Próspero («feliz e intrépido y sagaz») ha huido de una peste -una plaga que tiñe de carmesí los rostros de sus víctimas- para vivir con un millar de sus nobles y mujeres, bajo un lujo grotesco, en una abadía aislada, tras unos muros cerrados con hierro. En un fastuoso baile de máscaras, un invitado alto y demacrado llega para arruinar su imprudente diversión. Va vestido de hombre muerto: «La máscara que ocultaba el rostro estaba hecha de tal manera que se asemejaba al semblante de un cadáver rígido, y el escrutinio más minucioso debía tener dificultades para detectar el engaño». Está vestido como la mismísima Muerte Roja: «Su vestimenta estaba empapada de sangre, y su amplia frente, con todos los rasgos de su rostro, estaba salpicada del horror escarlata». Todos mueren, y como esto es Poe, mueren mientras un reloj de ébano da las doce de la noche (después de lo cual, hasta el reloj muere): «Y la Oscuridad y la Decadencia y la Muerte Roja tuvieron un dominio ilimitado sobre todo».

Más a menudo, sobrevive un vestigio de vida, un recordatorio de lo mucho que se ha perdido. En «La peste escarlata», de Jack London, publicada no mucho antes de la pandemia de gripe de 1918, un contagio mata a casi todos los habitantes del planeta; la historia se sitúa en 2073, sesenta años después del imaginado brote, cuando un puñado sobrevive, iletrado, «vestido de piel y en estado salvaje». Un hombre muy, muy viejo que, medio siglo antes, había sido profesor de inglés en Berkeley predice buenas noticias: «Nos estamos multiplicando rápidamente y preparándonos para un nuevo ascenso hacia la civilización». Aun así, no es tremendamente optimista, señalando: «Será lento, muy lento; es un ascenso tan grande. Hemos caído tanto. ¡Si sólo hubiera sobrevivido un físico o un químico! Pero no fue así, y lo hemos olvidado todo». Por esta razón, ha construido una especie de arca -una biblioteca- escondida en una cueva. «He almacenado muchos libros», dice a sus nietos analfabetos. «En ellos hay una gran sabiduría. Además, junto a ellos, he colocado una clave al alfabeto, para que el que conozca la escritura en imágenes pueda conocer también la letra impresa. Algún día los hombres volverán a leer».

Algún día los hombres volverán a leer. Lo primero que leerán, presumiblemente, será el propio libro que relata lo sucedido, en el que un narrador profético, parecido a Job, que ha sobrevivido al desastre, asume el sagrado deber de dirigirse a la posteridad. Como Ismael en «Moby-Dick», el superviviente deja torpemente un manuscrito, un mensaje en una botella, el último libro. «¡Aún estoy vivo!» son las últimas palabras de «Diario del año de la peste» de Daniel Defoe, un relato del brote de peste bubónica de 1665.

«El último hombre«, de Mary Shelley, se publicó en 1826, ocho años después de la publicación de «Frankenstein» y entre dos pandemias de cólera. En él, un hombre que se cree el único superviviente de un contagio mundial redacta un relato de la devastación -llamado «La historia del último hombre»– y luego parte en un barco entre cuyas escasas provisiones se encuentran las obras de Homero y Shakespeare. «Pero las bibliotecas del mundo están abiertas para mí», escribe en las últimas líneas del libro, «y en cualquier puerto puedo renovar mis existencias». Desaparece en su «pequeña barca», como si el mundo estuviese a punto de volver a empezar.

Las novelas con trama matrimonial terminan en bodas; las novelas con trama de peste terminan en funerales (siempre que quede alguien para enterrar a los muertos). El lector de «Emma«, de Jane Austen, nunca llega a saber cómo termina el matrimonio de Emma Woodhouse con el señor Knightley; el lector de «El último hombre» nunca llega a ver si la vida, después de la peste, continúa. Sin embargo, la literatura del contagio tiende a terminar, como la de Shelley, con un nuevo comienzo, una pizarra en blanco al estilo de John Locke, y, a veces, incluso con un indicio de que los males y errores de las viejas costumbres podrían no volver. Como afirmaba la campaña de Biden: «¡Construir de nuevo, mejor!».

En «Diario del año de la peste», la peste, magníficamente, se va. Es obra de Dios, no de ninguna medicina, concluye el narrador de Defoe. «Incluso los propios médicos se sorprendieron de ello«, escribe (aunque las medidas de salud pública adoptadas en Londres, incluida la cuarentena de los enfermos, habían supuesto una gran diferencia). La enfermedad retrocede tan repentinamente que la gente «se desprende de todos los temores, y lo hace demasiado rápido». Un hombre, aventurándose a salir, ve una multitud y lanza sus manos al aire, diciendo: «¡Señor, qué cambios hay! La semana pasada vine, y apenas se veía gente«. Otro hombre grita: «Todo es maravilloso, todo es un sueño». Defoe también termina su «relato de este año calamitoso» dando las gracias; su libro es, como el levantamiento de la plaga, «un llamamiento visible a todos para que demos Gracias».

Más difíciles de soportar, si uno se aferra con bastante desesperación a la promesa de construir algo mejor, son las historias en las que el problema, en el fondo, no es la peste sino la política. La novela de José Saramago «Ensayo sobre la ceguera», de 1995, sobre una plaga que reduce la visión de todos, termina con los ciegos recuperando la vista y abriendo los ojos para encontrar un mundo destruido. Pero la historia continúa en una secuela, llamada «Ensayo sobre la lucidez«, de 2004. Cuatro años después de la plaga de ceguera, los habitantes de la capital votan en unas elecciones municipales. Sin embargo, la mayoría de ellos emiten votos que han dejado en blanco. De alguna manera, los votos en blanco parecen otra plaga. «Lo que está ocurriendo aquí podría cruzar la frontera y extenderse como una muerte negra moderna», dice el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores. «Se refiere a una muerte blanca, ¿no?«, dice el Primer Ministro. Finalmente, los líderes deciden que los votos en blanco deben ser el resultado de una conspiración -un contagio político- y sitian la ciudad. Se contrata a un francotirador para que dispare a la única mujer de la capital que nunca perdió la vista, que siguió siendo totalmente inocente y veía la verdad. Todo el tiempo, el propio gobierno, sin visión, había sido la verdadera y duradera plaga.

La cesta de mi radiador, junto a la puerta de entrada, está llena de máscaras desechadas. Están hechas de papel blanco y tejidos azules y de algodón: florales, a cuadros, lisas. La mayoría huele a sudor y a saliva y, en menor medida, a jabón de lavandería. Son despreciadas. Fuera, la gente pasa, de luto, afligida, esperando, con esperanza. La última nieve se ha derretido. Incluso el aguanieve ha desaparecido.

«En aquellos días en los que la peste parecía retirarse, escurriéndose hacia la oscura guarida de la que había salido sigilosamente, al menos una persona de la ciudad veía la retirada con consternación«, escribe Albert Camus en «La peste«, de 1947. El número de muertos sigue disminuyendo, pero un hombre codicioso y de corazón duro, Cottard, que se ha beneficiado de la peste y no ha ayudado a los enfermos, empieza a sentir pánico. «¿De verdad crees que puede parar así, de repente?«, se pregunta. La gente del pueblo se acerca a lo que llaman «la vuelta a la vida normal», como animales que salen de una cueva después de una tormenta. Cottard no. «Parecía incapaz de retomar la vida oscura y monótona que había llevado antes de la epidemia. Se quedaba en su habitación y pedía que le enviaran la comida desde un restaurante cercano. Sólo al anochecer se aventuró a hacer algunas pequeñas compras». Las puertas de la ciudad están a punto de abrirse. La gente se alegra. «Pero Cottard no sonreía. ¿Se suponía, preguntó, que la peste no habría cambiado nada y que la vida de la ciudad seguiría como antes, exactamente como si no hubiera pasado nada?» Cottard saca una pistola y empieza a disparar a la gente en la calle. Se ha vuelto loco.

El narrador de «La peste» sabe lo mismo que Cottard: que la peste retiró la máscara que oculta la vileza egoísta y despiadada de los humanos. Pero también sabe algo que Cottard no sabía: que esa no es la última máscara, que bajo ella se esconde un verdadero rostro, el de la generosidad y la bondad, la misericordia y el amor. Al final de «La peste», su narrador se desenmascara a sí mismo: revela que es un médico que, tras haber atendido a los enfermos, resolvió escribir, «para no ser uno de los que callan, sino para dar testimonio a favor de los aquejados por la plaga; para que perdure algún recuerdo de la injusticia y el ultraje que se les hizo; y para afirmar simplemente lo que aprendemos en tiempo de peste: que hay más cosas que admirar en los hombres que las que despreciar». Más cosas, humanas al fin y al cabo.

Traducción: Marcos Villasmil

Jill Lepore es una historiadora estadounidense. Ejerce la Cátedra David Woods Kemper 41‘ de Historia Americana en la Universidad de Harvard, y es asimismo escritora en The New Yorker, donde colabora desde 2005. Es la presidente de la Sociedad de Historiadores estadounidenses y comisionada emérita de la Galería Nacional de Retratos del Smithsonian. Escribe sobre historia, derecho, literatura y política estadounidenses, y es autora de catorce libros, entre ellos «Estas verdades: Una historia de los Estados Unidos».

===================

NOTA ORIGINAL:

The New Yorker

Jill Lepore: How Do Plague Stories End?

In the literature of contagion, when society is finally free of disease, it’s up to humanity to decide how to begin again.

Last winter, when the gloom first fell, I saw an old woman, her back bent like a shepherd’s crook, walking watchfully through the freezing rain. She navigated the slush as she crossed the road, in black boots that she’d lined with plastic bags against the wet and the cold. She wore a mask the color of flesh, unnaturally smooth, but this was before everyone was wearing masks, and, at first, I couldn’t tell what it was: she looked as though she had no nose and no mouth. Closer, I could see the thing for itself, made—she must have stitched it herself—out of an old beige underwire bra, one cup cut off and turned upside down, the wire crimped onto the bridge of her nose, the thin nylon straps cinched around the back of her head. I stepped toward her, thinking I ought to say something: was she O.K.? Instantly her eyes widened and she turned away, quickening her pace. I never saw her again.

Not long after that, I started writing an essay about the literature of contagion, stories about plagues. Days, I read books. Nights, I sewed masks out of scraps of fabric and rubber bands, with paper towels for batting, folded inside like panty liners. I wondered about how plague stories begin, and what happens next. “All the world is topsy-turvy,” a character in one story says. “And it has been topsy-turvy ever since the plague.” Humans lose their humanity, according to the usual plot. As the pestilence spreads, people grow fearful of one another; families closet themselves in their houses. Stores take in their wares; schoolhouses bolt their doors. The rich flee; the poor sicken. The hospitals fill. The arts wither. Society descends into chaos, government into anarchy. Finally, in the last stage of this seemingly inevitable regression, in which history runs in reverse, books and even the alphabet are forgotten, knowledge is lost, and humans are reduced to brutes. In Octavia Butler’s 1984 novel, “Clay’s Ark,” set in the year 2021, the mutant survivors of an alien pathogen from Proxima Centauri 2 are “no longer human.” Lately, waiting for a shot of a vaccine, I’m hoping for another ending. Do the humans get to be human again?

Every plague leaves its mark on the world: crosses in our graveyards, blots of ink on our imaginations. Edgar Allan Poe had witnessed the ravages of cholera in Philadelphia, and he likely knew the story of how, in Paris, in 1832, the disease had struck at a ball, where guests turned violet blue beneath their masks. In Poe’s story “The Masque of the Red Death,” from 1842, Prince Prospero (“happy and dauntless and sagacious”) has fled a pestilence—a plague that stains its victims’ faces crimson—to live in grotesque luxury with a thousand of his noblemen and women in a secluded abbey, behind walls gated with iron. At a lavish masquerade ball, a tall, gaunt guest arrives to ruin their careless fun. He is dressed as a dead man: “The mask which concealed the visage was made so nearly to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse that the closest scrutiny must have difficulty in detecting the cheat.” He is dressed as the Red Death itself: “His vesture was dabbled in blood—and his broad brow, with all the features of his face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror.” Everyone dies, and because this is Poe, they die as an ebony clock tolls midnight (after which, even the clock dies): “And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

More often, a remnant of life survives—a reminder of just how much has been lost. In Jack London’s “The Scarlet Plague,” published not long before the 1918 flu pandemic, a contagion kills nearly everyone on the planet; the story is set in 2073, sixty years after the imagined outbreak, when a handful survive, unlettered, “skin-clad and barbaric.” One very, very old man who, a half century before, had been an English professor at Berkeley predicts good news: “We are increasing rapidly and making ready for a new climb toward civilization.” Still, he isn’t terrifically optimistic, noting, “It will be slow, very slow; we have so far to climb. We fell so hopelessly far. If only one physicist or one chemist had survived! But it was not to be, and we have forgotten everything.” For this reason, he has built a sort of ark—a library—hidden in a cave. “I have stored many books,” he tells his illiterate grandsons. “In them is great wisdom. Also, with them, I have placed a key to the alphabet, so that one who knows picture-writing may also know print. Some day men will read again.”

Some day men will read again. The first thing they’ll read, presumably, is the very book that chronicles what happened, in which a prophetic, Job-like narrator who has endured the disaster undertakes the sacred duty of addressing posterity. Like Ishmael in “Moby-Dick,” the survivor awkwardly leaves behind a manuscript—a message in a bottle, the very last book. “Yet I alive!” are the final words of Daniel Defoe’s “A Journal of the Plague Year,” an account of the 1665 outbreak of bubonic plague. Mary Shelley’s “The Last Man” was published in 1826, eight years after the publication of “Frankenstein,” and between two cholera pandemics. In it, a man who believes himself to be the sole survivor of a worldwide contagion pens an account of the devastation—called “The History of the Last Man”—and then sets off in a boat whose scant stores include the works of Homer and Shakespeare. “But the libraries of the world are thrown open to me,” he writes, in the book’s last lines, “and in any port I can renew my stock.” He disappears in his “tiny bark,” as if the world were beginning all over again.

Marriage-plot novels end with weddings; plague-plot novels end with funerals (so long as there’s anyone left to bury the dead). The reader of Jane Austen’s “Emma” never gets to find out how Emma Woodhouse’s marriage to Mr. Knightley pans out; the reader of “The Last Man” never gets to see whether life, after the plague, goes on. Still, the literature of contagion tends to end, like Shelley’s, with a new beginning, a Lockean blank slate—and, sometimes, even a hint that the evils of the old ways might not come back. As Biden’s campaign put it, “Build back better!”

In “A Journal of the Plague Year,” the pestilence, magnificently, passes. It is God’s doing, not the work of any medicine, Defoe’s narrator concludes. “Even the Physicians themselves were surprised at it,” he writes (although the public-health measures taken in London, including the quarantining of the sick, had made a great deal of difference). The disease retreats so suddenly that people “cast off all Apprehensions, and that too fast.” One man, venturing forth, sees a crowd and throws his hands into the air, saying, “Lord, what an alteration is here! Why, last Week I came along here, and hardly any Body was to be seen.” Another man cries, “’Tis all wonderful, ’tis all a Dream.” Defoe, too, finishes his “account of this calamitous year” by giving thanks; his book is, like the lifting of the plague, “a visible Summons to us all to Thankfulness.”

Harder to bear, if you are fairly desperately clinging to the promise of building back better, are stories in which the problem, at bottom, isn’t pestilence but politics. José Saramago’s novel “Blindness,” from 1995, about a plague that reduces everyone’s vision to whiteness, ends with the blind regaining their sight and opening their eyes to find a world destroyed. But the story continues in a sequel, called “Seeing,” from 2004. Four years after the plague of blindness, the people in the capital vote in a municipal election. Yet most of them cast ballots that they’ve left blank. Somehow, the blank votes look like another plague. “What is happening here could cross the border and spread like a modern-day black death,” the minister of foreign affairs says. “You mean blank death, don’t you,” the Prime Minister says. Eventually, these leaders decide the blank votes must be the result of a conspiracy—a political contagion—and lay siege to the city. A sniper is hired to shoot the only woman in the capital who never lost her sight, who remained utterly innocent and truth-seeing. All along, the sightless government itself had been the real, enduring plague.

The basket on my radiator by the front door is filled with cast-off masks. They’re made of white paper and blue tissue and cotton—floral, plaid, plain. Most of them smell like sweat and spit and, less, of laundry soap. They are despised. Outside, people walk past, mourning, grieving, waiting, hoping. The last snow has melted. Even the slush is gone.

“In those days when the plague seemed to be retreating, slinking back into the obscure lair from which it had stealthily emerged, at least one person in the town viewed the retreat with consternation,” Albert Camus writes in “The Plague,” from 1947. The death count keeps dropping, but one greedy and hard-hearted man, Cottard, who has profited from the plague, and failed to help the plague-stricken, begins to panic. “Do you really think it can stop like that, all of a sudden?” he wonders. The people of the town inch toward what they call “a return to normal life,” like animals emerging from a cave after a storm. Not Cottard. “He seemed unable to resume the obscure, humdrum life he had led before the epidemic. He stayed in his room and had his meals sent up from a near-by restaurant. Only at nightfall did he venture forth to make some small purchases.” The gates of the city are about to be opened. The people are rejoicing. “But Cottard didn’t smile. Was it supposed, he asked, that the plague wouldn’t have changed anything and the life of the town would go on as before, exactly as if nothing had happened?” Cottard gets out a gun and begins shooting at people in the street. He has gone mad.

The narrator of “The Plague” knows what Cottard knew: that the plague pulled back the mask that hides the selfish, ruthless, viciousness of humans. But he also knows something that Cottard did not: that this is not the last mask, that beneath it lies a true face, the face of generosity and kindness, mercy and love. At the end of “The Plague,” its narrator unmasks himself: he reveals that he is a doctor, who, having cared for the disease’s sufferers, resolved to write, “so that he should not be one of those who hold their peace but should bear witness in favor of those plague-stricken people; so that some memorial of the injustice and outrage done to them might endure; and to state quite simply what we learn in time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.” More things, human after all.

Jill Lepore, a staff writer at The New Yorker, is a professor of history at Harvard and the author of fourteen books, including “If Then: How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future.”