Jill Lepore: The Speech

Have Inaugural Addresses been getting worse?

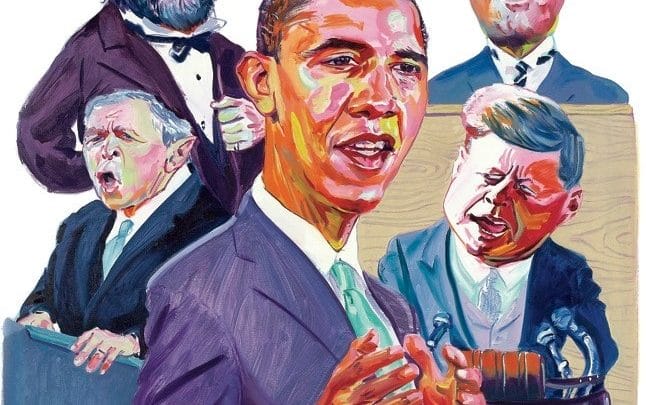

Barack Obama has been studying up, reading Abraham Lincoln’s speeches, raising everyone’s expectations for what just might be the most eagerly awaited Inaugural Address ever. Presidential eloquence doesn’t get much better than the argument of Lincoln’s first inaugural, “Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy”; the poetry of his second, “Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away”; and its parting grace, “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in.”

Reading Lincoln left James Garfield nearly speechless. After Garfield was elected, in 1880, he, like most of our more bookish Chief Executives, or at least their speechwriters, undertook to read the Inaugural Addresses of every President who preceded him. “Those of the past except Lincoln’s, are dreary reading,” Garfield confided to his diary. “I have half a mind to make none.” Lincoln’s are surpassingly fine; most of the rest are utterly unlovely. The longest are, unsurprisingly, the most vacuous; it usually takes a while to say so prodigiously little. “Make it the shortest since T.R.,” John F. Kennedy urged Ted Sorensen, who, on finishing his own reading, reported, “Lincoln never used a two- or three-syllable word where a one-syllable word would do.” Sorensen and Kennedy applied that rule to the writing of Kennedy’s inaugural, not just the “Ask not” but also the “call to”: “Now the trumpet summons us again—not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need; not as a call to battle, though embattled we are—but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle.”

Economy isn’t everything. “Only the short ones are remembered,” Richard Nixon concluded, after reading all the inaugurals, an opinion that led him to say things briefly but didn’t save him from saying them badly: “The American dream does not come to those who fall asleep.” Even when Presidential inaugurals make more sense than that, they are not, on the whole, gripping. “The platitude quotient tends to be high, the rhetoric stately and self-serving, the ritual obsessive, and the surprises few,” Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., observed in 1965, and that’s still true. A bad Inaugural Address doesn’t always augur a bad Presidency. It sinks your spirit, though. In 1857, James Buchanan berated abolitionists for making such a fuss about slavery: “Most happy will it be for the country when the public mind shall be diverted from this question to others of more pressing and practical importance.” Ulysses S. Grant groused, “I have been the subject of abuse and slander scarcely ever equaled in political history.” Dwight D. Eisenhower went for a numbered list. George H. W. Bush compared freedom to a kite. For meaninglessness, my money’s on Jimmy Carter: “It is that unique self-definition which has given us an exceptional appeal, but it also imposes on us a special obligation to take on those moral duties which, when assumed, seem invariably to be in our own best interests.” But, for monotony, it’s difficult to outdrone Warren G. Harding (“It is so bad that a sort of grandeur creeps into it,” H. L. Mencken admitted): “I speak for administrative efficiency, for lightened tax burdens, for sound commercial practices, for adequate credit facilities, for sympathetic concern for all agricultural problems, for the omission of unnecessary interference of . . .” I ellipse, lest I nod off. The American dream does not come to those who fall asleep.

When Garfield was elected, there were fewer inaugurals to plow through, but they were harder to come by. Obama might not be allowed to e-mail, but he can still Google. Sorensen, who mimeographed, had merely to walk over to the Library of Congress. Garfield’s staff had to hunt down every inaugural, and any copying they did they did by hand. The inaugurals weren’t regularly compiled and printed as a set until 1840, in “The True American,” and, six years later, in “The Statesman’s Manual,” but by 1880 no edition remained in print, and Garfield’s men had to cobble them together all over again. Since 1893, a complete set of texts has been reissued every few decades or so, including, this past year, in “Fellow Citizens: The Penguin Book of U.S. Presidential Inaugural Addresses” (Penguin; $16), edited, with an introduction and commentaries, by Robert V. Remini and Terry Golway.

Inaugural Addresses were written to be read as much as heard. Arguably, they still are. The first thirty-three of our country’s Inaugural Addresses survive only as written words. Before 1921, when Warren Harding used an amplifier, even the crowd couldn’t make out what the President was saying, and before Calvin Coolidge’s speech was broadcast over the radio, in 1925, the inaugurals were, basically, only read, usually in the newspaper. Since Truman’s, in 1949, inaugurals have been televised, and since Bill Clinton’s second, in 1997, they have been streamed online. Obama’s inaugural, the fifty-sixth in American history, will be the first to be YouTubed. “Our Founders saw themselves in the light of posterity,” Clinton said. “We can do no less.” Inaugurals are written for the future, but they look, mostly, to the past (“We are the heirs of the ages,” T.R. said), which, when you think about it, might help explain why so many prove so unsatisfying in the present. (“Achieve timelessness! ” is, as a piece of writing advice, probably not the most helpful.) On January 20th, most of us will watch and listen. Delivery counts. But, for now at least, speaking to posterity still means writing for readers. Bedside reading old inaugurals are not. But they do offer some hints about what will be at stake when Barack Obama raises his hands, quiets the crowd, and clears his throat.

“Made the first actual study for inaugural by commencing to read those of my predecessors,” Garfield wrote in his diary on December 20, 1880, when he still had plenty of time. (New Presidents used to be sworn in on March 4th. In 1933, the Twentieth Amendment changed the date to January 20th, to shorten the awkward interregnum between election and Inauguration.) He started with George Washington’s first (the oldest) and second (at a hundred and thirty-five words, the shortest). The next day, he read John Adams’s overworked and forgettable one and only: “His next to the last sentence contains more than 700 words. Strong but too cumbrous.” (Actually, Garfield was wrong; it’s the third-to-last sentence. But it is cumbrous. Also, indefinite: nineteen of those seven hundred words are “if.”) That afternoon, Garfield listened as a friend read aloud Thomas Jefferson’s first, probably more forcefully than had Jefferson, who was, famously, a mumbler. “Stronger than Washington’s, more ornate than Adams’ ” was the President-elect’s verdict on the address, widely considered nearly as transcendent as Lincoln’s two, for these lines: “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” But it’s the next, if admittedly more ornate, sentence that steals my breath: “If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.”

On December 22nd, Garfield trudged through a few more lesser addresses: “Curious tone of self-depreciation runs through them all—which I cannot quite believe was genuine. Madison’s speeches were not quite up to my expectations. Monroe’s first was rather above.” And then, what with Christmas, trips to the dentist, and choosing a Cabinet, Garfield found his interest in reading inaugurals flagging. Instead, he devoured a novel, hot off the presses—Disraeli’s three-volume, autobiographical “Endymion.” He finished it on New Year’s Eve, just weeks after he started it, and concluded in his diary, twenty minutes before midnight, “It shows adroitness, great reserve on dangerous questions, with enough frankness on other questions to make a show of boldness.” Even that much he could not say for the inaugurals stretching from John Quincy Adams (who wore pants instead of knee breeches) to Buchanan (a man Kennedy once aptly described as “cringing in the White House, afraid to move,” while the nation teetered on the brink of civil war). By mid-January, Garfield’s staff had entered summaries of the inaugurals into a book for him to read. But, abridged or unabridged, they were a slog. Did he really have to write one? He wasn’t so sure: “I am quite seriously discussing the propriety of omitting it.”

He could have. The Constitution says nothing about an Inaugural Address. It calls only for the President to take an oath: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” George Washington took that oath in New York City, on April 30, 1789 (the election hadn’t been concluded until mid-April). Just hours before the ceremony, a special congressional committee decided that it might be fitting for Washington to rest his hand on a Bible, and, since no one in Federal Hall had a copy, there followed a mad dash to find one. At midday, Washington took his oath standing on a balcony above a crowd assembled on Wall Street. Then he kissed his borrowed Bible and uttered four words more: “So help me, God.” Ever since, most Presidents have done the same, but some have dispensed with the kiss, a few have skipped those four words, and, in 1853, Franklin Pierce even refused the Bible.

After Washington was sworn in, he entered Federal Hall and made a speech before Congress. He didn’t have to. He thought it would be a good idea. Like most things Washington did, this set a precedent. Washington’s first inaugural was addressed to “Fellow-Citizens of the Senate and the House of Representatives.” He wasn’t speaking to the American people; he was speaking to Congress. In 1801, Jefferson, the first President to be inaugurated in Washington, D.C., the nation’s new capital, addressed his remarks to the American people—“Friends and Fellow-Citizens”—but, the day he delivered it, he, too, was really speaking only to Congress and assorted dignitaries, assembled in the half-built Capitol. James Monroe, in 1817, was the first to deliver his inaugural in the open air (before a crowd of eight thousand, who couldn’t hear a thing), although this came about only because the Capitol was undergoing renovations and House members refused to share a chamber with the senators. In 1829, some twenty thousand Americans turned up for Andrew Jackson’s Inauguration. Jackson, who had campaigned as a common man, addressed his inaugural to the American people, and that’s how it has been done ever since. Talking to the American people proved to be the death of William Henry Harrison, who, on a bitterly cold and icy day in 1841, became, at sixty-eight, the oldest President then to have taken office. Determined to prove his hardiness, Harrison delivered his address hatless and without so much as an overcoat. “In obedience to a custom coeval with our Government and what I believe to be your expectations I proceed to present to you a summary of the principles which will govern me in the discharge of the duties which I shall be called upon to perform,” Harrison said, introducing a speech that, far from being a summary, took more than two hours to deliver, and, at more than eight thousand words, still reigns as the longest. Harrison caught a cold that day; it worsened into pneumonia; he died a month later.

“I must soon begin the inaugural address,” Garfield scolded himself in his diary on January 25, 1881. He had finished his dreary reading. There was no real avoiding the writing. “I suppose I must conform to the custom, but I think the address should be short.” Three days later, he reported, “I made some progress in my inaugural, but do not satisfy myself. The fact is I ought to have done it sooner before I became so jaded.”

George Washington wasn’t jaded, but he struggled, too. Possibly with the help of David Humphreys, he wrote the better part of a first draft, seventy-three pages of policy recommendations. Eager to assure Americans that he had not the least intention of founding a dynasty, he reminded Congress that he couldn’t: “the Divine providence hath not seen fit that my blood should be transmitted or my name perpetuated by the endearing though sometimes seducing, channel of personal offspring.” James Madison judiciously deleted that. Jackson made a stab at a draft, but his advisers, calling it “disgraceful,” rewrote it entirely. After reading a draft of William Henry Harrison’s inaugural, cluttered with references to ancient republics, Daniel Webster pared it down, and declared when he was done, “I have killed seventeen Roman pro-consuls as dead as smelts.”

Lincoln gave a draft of his first inaugural to his incoming Secretary of State, William Seward, who scribbled out a new ending, offering an olive branch to seceding Southern states:

But it was Lincoln’s revision that made this soar:

Revision usually helps. Raymond Moley drafted Franklin Roosevelt’s first inaugural, but Louis Howe added, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Sorensen wrote much of Kennedy’s, but it was Adlai Stevenson and John Kenneth Galbraith who proposed an early version of “Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.” Carter, who had a vexed relationship with speechwriters, wrote his own unmemorable inaugural, although James Fallows managed to persuade him to open by thanking Gerald Ford. In “White House Ghosts: Presidents and Their Speechwriters” (Simon & Schuster; $30), Robert Schlesinger argues that Ronald Reagan gave, in the course of his career, iterations of what was essentially the same talk, known as the Speech. His inaugural, remarkable for its skilled delivery, was no exception. Clinton solicited advice from dozens of people, including Sorensen, and then tinkered. About her husband, Hillary Clinton once said, “He’s never met a sentence he couldn’t fool with.”

James Garfield wrote his inaugural alone. “I must shut myself up to the study of man’s estimate of himself as contrasted with my own estimate of him,” he vowed, with much misgiving, in mid-January. “Made some progress on the inaugural,” he reported a few weeks later, “but still feel unusual repugnance to writing.” At least he had settled on an outline: “1st a brief introduction, 2nd a summary of recent topics that ought to be treated as settled, 3rd a summary of those that ought to occupy the public attention, 4[th] a direct appeal to the people to stand by me in an independent and vigorous execution of the laws.” In “Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words” (Chicago; $25), Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson argue that inaugural rhetoric serves four purposes: reuniting the people after an election; rehearsing shared and inherited values; setting forth policies; and demonstrating the President’s willingness to abide by the terms of his office. That list happens to be a near-match to Garfield’s outline. But it misses what has changed about inaugurals over the years, and what was newish about Garfield’s. The nation’s first century of inaugural speeches, even when they were addressed to the people, served to mark an incoming President’s covenant with the Constitution. As the political scientist Jeffrey Tulis pointed out in his 1987 study, “The Rhetorical Presidency,” every nineteenth-century inaugural except Zachary Taylor’s mentions the Constitution. John Quincy Adams called that document our “precious inheritance.” To Martin Van Buren, it was “a sacred instrument.” James K. Polk called it “the chart by which I shall be directed.” Most do more than mention the Constitution; they linger over it. A few nineteenth-century inaugurals, including William Henry Harrison’s, consist of ponderous constitutional analysis. Meanwhile, only half the inaugurals delivered in the twentieth century contain the word “Constitution,” and none do much more than name it. Nineteenth-century Presidents pledged themselves to the Constitution; twentieth-century Presidents courted the American people.

We now not only accept that our Presidents will speak to us, directly, and ask for our support, plebiscitarily; we expect it, even though the founders not only didn’t expect it, they feared it. Tulis and other scholars who wrote on this subject during the Reagan years generally found the rise of the rhetorical Presidency alarming. By appealing to the people, charismatic Chief Executives were bypassing Congress and ignoring the warnings of—and the provisions made by—the Founding Fathers, who considered popular leaders to be demagogues, politicians who appealed to passion rather than to reason. The rhetorical Presidency, Tulis warned, was leading to “a greater mutability of policy, an erosion of the processes of deliberation, and a decay of political discourse.”

In the years since, that prediction has largely been borne out. Still, scholars have quibbled about Tulis’s theory. In the latest corrective, “The Anti-Intellectual Presidency: The Decline of Presidential Rhetoric from George Washington to George W. Bush” (Oxford; $24.95), the political scientist Elvin T. Lim argues that the problem isn’t that Presidents appeal to the people; it’s that they pander to us. Speech is fine; blather is not. By an “anti-intellectual President”—a nod to Richard Hofstadter’s “Anti-Intellectualism in American Life,” from 1963—Lim doesn’t just mean George W. Bush, though Bush’s government-by-the-gut is a good illustration of his point. He means everyone from Harding forward (except for T.R., Wilson, F.D.R., and J.F.K., who, while rhetorical Presidents, were not, by Lim’s accounting, anti-intellectual ones), a procession of Presidents who have, in place of evidence and argument, offered platitudes, partisan gibes, emotional appeals, and lady-in-Pasadena human-interest stories. Sloganeering in speechwriting has become such a commonplace that this year the National Constitution Center is hosting a contest for the best six-word inaugural. (“New deal. New day. New world.”) Public-spirited, yes; nuanced, not so much.

Lim dates the institutionalization of the anti-intellectual Presidency to 1969, when Nixon established the Writing and Research Department, the first White House speechwriting office. There had been speechwriters before, but they were usually also policy advisers. With Nixon’s Administration was born a class of professionals whose sole job was to write the President’s speeches, and who have been rewarded, in the main, for the amount of applause their prose could generate. Of F.D.R.’s speeches, only about one a year was interrupted for applause (and no one applauded when he said that fear is all we have to fear). Bill Clinton’s last State of the Union address was interrupted a hundred and twenty times. The dispiriting transcript reads, “I ask you to pass a real patients’ bill of rights. [Applause.] I ask you to pass common sense gun safety legislation. [Applause.] I ask you to pass campaign finance reform. [Applause.]” For every minute of George W. Bush’s State of the Union addresses, there were twenty-nine seconds of applause.

Lim interviewed forty-two current and former White House speechwriters. But much of his analysis rests on running inaugurals and other Presidential messages through something called the Flesch Readability Test, a formula involving the average number of words in a sentence and the average number of syllables per word. Flesch scores, when indexed to grade levels, rate the New York Times at college level; Newsweek at high school; and comic books at fifth grade. Between 1789 and 2005, the Flesch scores of Inaugural Addresses descended from a college reading level to about an eighth-grade one. Lim takes this to mean that Inaugural Addresses are getting stupider. That’s not clear. They’ve always been lousy. Admittedly, the older speeches are, as Garfield put it, cumbrous, but it’s a mistake to assume that something’s smarter just because it’s harder to read. This essay, with the exception of the sentence after this one, gets an eleventh-grade rating. However, were circumstances such that a disquisition on Presidential eloquence were to proffer, to a more loquacious narrator—one whose style and syntax were characterized by rhetorical flourishes which, to modern ears, might, indeed, give every appearance of being at once extraordinary and antiquated, and, yet more particularly, obnoxious—were, that is, this composition to present to such a penman a propitious opportunity for maundering, not to say for circumlocution, that tireless soul would be compensated, if a dubious reward it would prove, by a Flesch score more collegial, nay: this extracted digression rates “doctoral.” It is, nevertheless, malarkey. Flesch scores turn out to be not such a useful measure of meaningfulness, especially across time. Still, Lim is onto something. The American language has changed. Inaugural Addresses can be lousy in a whole new idiom. The past half century of speechwriters, most of whom trained as journalists, do favor small words and short sentences, as do many people whose English teachers made them read Strunk and White’s 1959 “Elements of Style” (“Omit needless words”) and Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” (“Never use a long word where a short one will do”). Lim gets this, but only sort of. Harding’s inaugural comes in at a college reading level, George H. W. Bush’s at about a sixth-grade level. Harding’s isn’t smarter or subtler; it’s just more flowery. They are both empty-headed; both suffer from what Orwell called “slovenliness.” The problem doesn’t lie in the length of their sentences or the number of their syllables. It lies in the absence of precision, the paucity of ideas, and the evasion of every species of argument.

Presidential rhetoric is worth keeping an eye on. But the anti-intellectual Presidency is fast expiring. And a rhetorical Presidency begins to look a lot better, after some years of a dumbfounded one.

Three days before his Inauguration, James Garfield scrapped his entire first draft and started again. (Actually, he didn’t quite scrap it; he filed it. You can read his several drafts at the Library of Congress.) He finished his speech at two-thirty in the morning, just hours before he became President (thereby beating Clinton, who put down his pen at 4:30 a.m.). He began, as almost everyone does, with a history lesson: “We can not overestimate the fervent love of liberty, the intelligent courage, and the sum of common sense with which our fathers made the great experiment of self-government.” The American experiment had been Washington’s theme, too. “The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government,” Washington said, are, finally, “staked on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.” John Adams deemed this “an experiment better adapted to the genius, character, situation, and relations of this nation” than of any other. Jefferson called the American republic “the world’s best hope.”

Antebellum Presidents couldn’t very well avoid attempting to explain the relationship between the American experiment and the peculiar institution. Van Buren acknowledged the issue of slavery as a source of “discord and disaster”; he therefore praised the founders’ “forbearance” of it. William Henry Harrison urged the same: “The attempt of those of one State to control the domestic institutions of another can only result in feelings of distrust and jealousy, the certain harbingers of disunion, violence, and civil war, and the ultimate destruction of our free institutions.” Pierce, sworn into office three years after the Compromise of 1850, went further: “I believe that involuntary servitude, as it exists in different States of this Confederacy, is recognized by the Constitution.” Lincoln was the first to state the matter plainly: “One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.” In his extraordinary second inaugural—it’s hard to think of a better speech that he, or anyone, could have given—he asked the Union to forgive the Confederacy: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged.”

Garfield, who wrestled, alone in his study, with man’s estimation of man, proved to be the first post-Civil War President to achieve anything like Lincoln’s capacity for uncompromising argument married to relentless grace. “The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution,” Garfield observed. And then, about the Southern suppression of the black vote, he warned, “To violate the freedom and sanctities of the suffrage is more than an evil. It is a crime which, if persisted in, will destroy the Government itself.” William McKinley, in the first inaugural of the twentieth century, announced, “We are reunited. Sectionalism has disappeared.” It had not. It has not. In 1909, a hundred years before Barack Obama’s Inauguration, William Taft was left insisting, because so many Americans still needed reminding, “The negroes are now Americans.”

There have been a lot of speeches since then, but, as Clinton said in his second inaugural, “The divide of race has been America’s constant curse.” Obama, in his ambitious March, 2008, speech on race, attempted to lift that curse. “America can change—that is the true genius of this nation,” he declared. “This union may never be perfect, but generation after generation has shown that it can always be perfected.”

Generations ago, James Garfield did his imperfect best. The inaugural he delivered, on March 4, 1881, didn’t match Lincoln’s eloquence. But this year it bears rereading:

Enough said. ♦

Jill Lepore, a staff writer at The New Yorker, is a professor of history at Harvard and the author of fourteen books, including “If Then: How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future.”