La vida espiritual de Arthur Conan Doyle

Siendo un joven médico que vivía en Inglaterra en la década de 1880, Arthur Conan Doyle comenzó a asistir a sesiones de espiritismo en las que los médiums ofrecían contacto con los muertos. También observó demostraciones de telepatía psíquica, escritura automática e inclinación de la mesa, y se convenció de que había un mundo invisible. Católico no practicante, pasó entonces a anunciarse como espiritista, pero no comienza a hacer proselitismo por su nuevo credo hasta la Primera Guerra Mundial. La muerte de su hijo mayor, Kingsley (en 1918), de su hermano (al año siguiente) y de dos sobrinos (poco después de la guerra) lo llevó a abrazar el espiritismo con todo su corazón, convencido de que era una «Nueva Revelación» entregada por Dios para consolar a los afligidos.

En 1920, Conan Doyle, ya famoso durante mucho tiempo como el creador de Sherlock Holmes, recibió una carta de un amigo emocionado que tenía en su poder una fotografía en la que pequeños seres femeninos con alas diáfanas se divierten frente a una adolescente fascinada. La niña era Elsie Wright, de 16 años, que vivía cerca de la aldea de Cottingley en Yorkshire, y la foto había sido tomada por su prima de 10 años, Frances. Las niñas reportaron haber visto previamente a las hadas junto a un arroyo y que luego regresaron con una cámara prestada por el padre de Elsie para que Frances pudiera tomar una foto de ella con las criaturas místicas.

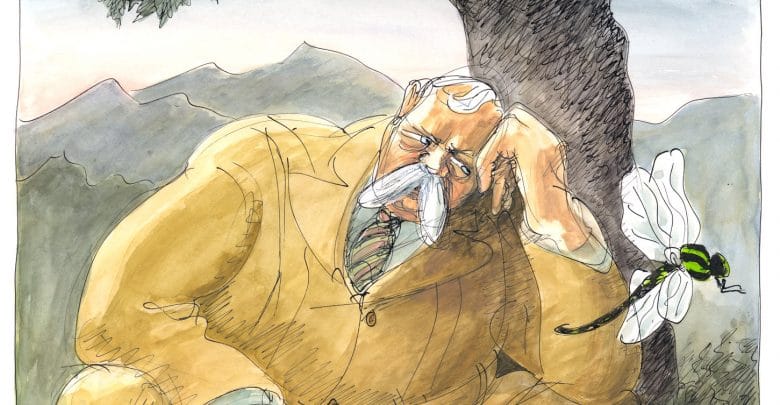

Si Sherlock Holmes hubiera visto esa imagen inicial, sin duda habría notado que aunque una brisa había hecho que las hojas de los árboles se desdibujaran, las alas de las hadas voladoras no mostraban movimiento. Conan Doyle, sin embargo, consideró la fotografía como genuina. Cuando aparecieron más fotografías de hadas el mismo año, escribió dos artículos y un libro de no ficción, «La venida de las hadas», en el que insistía en que las figuras representadas eran hadas verdaderas. Su creencia le valió la condena de la prensa, del público y, paradójicamente, de las iglesias cristianas, cuyo propio sistema de creencias incluía ángeles alados y demonios.

El escritor se mantuvo convencido de la existencia de las hadas hasta su muerte en 1930. Tanto su familia como sus amigos espiritualistas se negaron a llevar ropa de luto al funeral como una forma de expresar su convicción de que el autor simplemente había pasado a existir en otra dimensión. Seis mil personas se congregaron en el Albert Hall ese día, muchas de ellas esperando que su mentor fallecido se pusiera en contacto. Su viuda no fue la única que juró que lo hizo.

En 1983, una Elsie Wright mucho mayor finalmente reconoció el engaño: Había cortado las hadas de un libro infantil ilustrado y luego las había sostenido con hilos invisibles para que Frances pudiera fotografiarla sonriendo en el recorte. Lamentablemente, Elsie no vivió lo suficiente para que el mundo fuera testigo de lo que podría haber hecho con Photoshop.

Traducción: Marcos Villasmil

NOTA ORIGINAL:

The New York Times

The Spiritual Life of Arthur Conan Doyle

As a young doctor living in England in the 1880s, Arthur Conan Doyle began attending séances where mediums offered contact with the dead. He also observed displays of psychic telepathy, automatic writing and table tipping, and became convinced that there was an unseen world out there. A lapsed Catholic, he now announced himself a Spiritualist, but did not begin proselytizing for his new creed until World War I. The deaths of his oldest son, Kingsley (in 1918), his brother (the following year) and two nephews (shortly after the war) led him to embrace Spiritualism with all his heart, convinced it was a “New Revelation” delivered by God to console the bereaved.

In 1920, Conan Doyle, now long famous as the creator of Sherlock Holmes, received a letter from an excited friend who was in possession of a photograph in which tiny females with diaphanous wings are cavorting in front of an entranced adolescent girl. The girl was 16-year-old Elsie Wright, who lived near the village of Cottingley in Yorkshire, and the photo had been taken by her 10-year-old cousin, Frances. The girls reported having previously seen the fairies by a stream and then gone back with a camera borrowed from Elsie’s father so Frances could take a picture of her with the mystical creatures.

Had Sherlock Holmes seen that initial image, he would no doubt have noticed that although a breeze had caused the leaves on the trees to blur, the wings of the flying fairies showed no movement. Conan Doyle, however, regarded the photograph as genuine. When more photographs of fairies showed up the same year, he wrote two articles and a nonfiction book, “The Coming of the Fairies,” in which he insisted that the figures depicted were actual fairies. His belief earned him condemnation from the press, the public and, ironically, Christian churches, whose own belief system encompassed winged angels and devils.

The writer remained convinced of the existence of fairies until his death in 1930. Both his family and Spiritualist friends refused to wear mourning clothes to the funeral as a way of expressing their conviction that the author had simply moved on to exist in another dimension. Six thousand people crowded into Albert Hall that day, many hoping that their departed mentor would make contact. His widow was not alone in swearing he did.

In 1983, a much older Elsie Wright finally owned up to the hoax: She had cut the fairies out of an illustrated children’s book and then held them up with invisible threads so Frances could photograph her smiling at the cutout. Regrettably Elsie did not live long enough for the world to witness what she could have done with Photoshop.

Edward Sorel, a caricaturist and muralist, is the author and illustrator of “Mary Astor’s Purple Diary.”