Monday, Monday: Llanto púrpura por el genio de Prince

Ha fallecido Prince. Medios de todo el mundo han reseñado la noticia. En América 2.1 nos unimos a la cálida despedida que se le ha hecho. Para ello, hemos escogido algunas notas de la prensa mundial que creemos merecen difusión.

En su legado quedan más de 100 millones de discos vendidos, 7 premios Grammy, y su merecida entrada al Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll en 2004.

A continuación notas de El País, The Economist y New York Times.

Marcos Villasmil / América 2.1

————————————————————

Llanto púrpura por el genio de Prince

La muerte a los 57 años del músico de Minneapolis causa una conmoción global

Diego Manrique – El País

Permitánme usar las mayúsculas: fue el Gran Músico de su generación. Da la casualidad que Prince, hallado muerto este jueves, compartía año de nacimiento (1958) con Michael Jackson y Madonna. Como ellos, su ambición parecía ilimitada pero, en el caso de Prince Rogers Nelson, estaba respaldada por una inmensa capacidad creativa: podía grabar en solitario, tocando todos los instrumentos e incluso cambiando de voz. Era tan prolífico que acumuló centenares de temas en el archivo de Paisley Park, su Xanadu de Minneapolis.

Su paleta musical abarcaba desde el funk implacable al pop psicodélico, pasando por el rock duro; en disco, solo se le resistió el rap. La exhibición de su talento resultaba tan apabullante que, en 1977, Warner le concedió plena libertad para autoproducirse, algo impensable para un desconocido que todavía no había cumplido los 20 años. Tras cinco discos contundentes, ascendió a artista global en 1984 con Purple rain, la banda sonora de una película que mitificaba sus comienzos y la escena de Minneapolis. Le acompañaba The Revolution, significativamente una banda mixta en sexo y raza: Prince ignoraba las reglas, incluyendo las ortográficas.

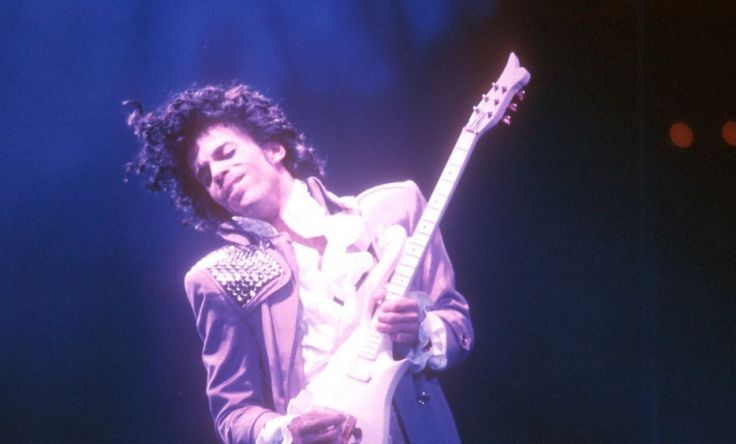

Prince interpretando «Purple Rain»

Resumiendo: los ochenta fueron suyos. Michael Jackson pudo vender más discos y, sin duda, Madonna ocupó más espacio mediático pero, musicalmente hablando, nadie podía compararse con Prince. Se reinventaba con lanzamientos como Around the world in a day (1985) o Sign o’ the times (1987). Parecía multiplicarse, gracias a las canciones que interpretaban Sheena Easton, Sinèad O’Connor o las Bangles; a través de su sello, Paisley Park Records, facturaba variaciones sobre sus hallazgos y hasta rescataba a predecesores tipo George Clinton o Mavis Staples. Brevemente, pareció que el sonido del momento se cocinaba en Minneapolis, con sus discos y los que producían antiguos compañeros, como el tándem Jimmy Jam-Terry Lewis.

Pero el imperio tenía pies de barro. Convertido en director de sus propias fantasías, firmó dos películas que resultaron caprichos autocomplacientes: Under the cherry moon (1986) y Graffiti Bridge (1990). Pincharon, al igual que muchos de los discos que sacaba en su sello. Warner Music cortó la financiación y comenzó un enfrentamiento que dejó en mal lugar a ambas partes.

Esencialmente, Warner pretendía regular la incontinencia creativa de Prince, para someterla a planes de marketing: la compañía había demostrado que podían devolverle al nº 1 con la música de Batman. Pero Prince se declaró en rebeldía: sacó discos de mala gana, cumpliendo su contrato con material de relleno. A la larga, esto derivó en una desconfianza total hacia las grandes discográficas, actitud que ha contribuido a obscurecer su carrera durante los últimos veinticinco años. El celo por defender su arte convirtió a Prince en un personaje difícil de tratar, con una tendencia funesta a irritar a sus fieles más activos. Daba bandazos y se explicaba mal. Apostó por Internet y luego renegó: últimamente, parecía haber desaparecido de YouTube o Spotify.

Sabíamos poco sobre la persona que había detrás. Era reacio a las entrevistas, convertidas a veces en enigmáticas performances. El libertino de los primeros tiempos, que provocó la movilización de la esposa de Al Gore y demás damas bienpensantes de Washington, se reconvirtió en Testigo de Jehová, aunque lanzaba suficientes guiños para sugerir que no obedecía rigurosamente las leyes de su religión. Había anunciado un libro autobiográfico que uno imaginaba que sería otra pirueta evasiva.

Prince y Lenny Kravitz, interpretando «American Woman»

Lo que conviene saber es que, aunque de modo espasmódico, continuó editando música extraordinaria, no siempre promocionada adecuadamente ni disponible en todos los puntos de venta. Le salvó, claro, la potencia de sus directos, principal fuente de ingresos y territorio libre de limitaciones. Allí exhibía su poderío como guitarrista y su magnetismo como líder de banda. Se trataba de conciertos extensos e imprevisibles, que podía prolongar con jam sessions en otro local.

En esas noches mágicas te olvidabas de todas sus incongruencias y decidías que sí, que no había un artista comparable. Una salvaje mezcla de Jimi Hendrix y James Brown, un sintetizador de la mejor música afroamericana de la segunda mitad del siglo XX que, y no deberíamos sorprendernos, también amaba a cantautoras eruditas como Joni Mitchell. Nos queda su misterio, el eco de sus prodigios, un hueco imposible de rellenar.

———————————————————-

His purple highness – Everything flowed through Prince

The Economist

PRINCE, one criticism runs, was too talented. Ideas flowed through him like rain passing through a leaky roof, so much so that he would struggle to find enough pots and pans to catch it in. It is true that few artists have been so prolific. On average, he released a studio album every year between his first, “For You”, in 1978, and “HITnRUN Phase Two” in 2015, the last before his death on April 21st, aged 57. Perhaps he could have been a better filter for his material. By the end, the deluge became overwhelming, and albums stopped catching the mood of the public as his earlier work had. Even “Sign o’ the Times”, his 1987 double-length masterpiece, said the doubters, might be thought of as one of the greatest single-length albums never released.

But what those with lesser creativity didn’t understand was that such a flow is not so easily staunched. To listen to Prince was to hear an orchestra of one. He liked working in solitude because it cut him off from outside voices, or perhaps because there were too many in his own head. He was, as he wrote on the back of his first demo tape, writer, producer, arranger, musician and singer. Even without four of those titles, he would be remembered as one of his generation’s great guitarists.

Prince Rogers Nelson was born in Minneapolis, the son of two Louisiana-bred jazz musicians. Listening to his parents play, he knew early what life held for him. One demo, recorded in 1976 at the age of 17, and on which he played every instrument, was all it took to sign a manager. Success followed swiftly. In 1979, his second album, “Prince”, a work of raunchy R&B, went platinum. Yet for all his solitudinal studio habits, his purplest patch came when he recruited The Revolution, a band including Jill Jones and Lisa Coleman. That brief period, between 1984 and 1987, encompassed the albums “1999”, “Around the World in a Day” and “Parade”. Above all, Prince and the Revolution made “Purple Rain” in 1984, selling 13m copies and launching a film of the same name, with Prince in the starring role. It made him a global star—one of the first black musicians to rule in the age of MTV.

It was not only in Paisley Park, his studio in Minneapolis, that he proved tireless. On the road, too, he was relentless. It was difficult to know which was his more natural home: the stage or the sound desk. He toured 28 times between 1979 and 2015. Anyone who saw him wondered where he found the energy to strut and grind through three hours of crowd-pleasers. Yet even that didn’t exhaust him. Within an hour of coming off stage at some enormodome or other, he could often be found playing an after-show set for a small crowd in a nearby club, working his guitar just for the pleasure of it.

Yet he was intensely private and shy. Rarely did he give interviews. When he did, he found it hard to hold the interrogator’s eye, mumbling nervously. He preferred to speak through his music. On that score little ground was given. In 1993 he changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol, in protest against Warner Brothers, his long-standing record label, who had the temerity to suggest he stagger his output so as not to saturate the market. At that time, it was said, he had a surplus of some 500 songs waiting for release.

His music could range from the whitest rock to the blackest soul. (Although when asked whether white people could understand his music, he replied that of course they couldn’t: “You have to live a life to understand it. Tourists just pass through.”) That made him a slippery character to grasp. He was the teetotaler, and later a Jehovah’s Witness, who sang of women “in a hotel lobby masturbating with a magazine”. (Those lyrics would persuade Tipper Gore to campaign for the introduction of Parental Advice stickers on albums.) But sex was his thing; the thread linking it all. Some suggested his obsession for the libidinous stemmed from his mother who had, the story goes, taught him the facts of life by buying him pornographic magazines. Or maybe it was a way of compensating for his stature (he stood just 5’2” [1.57m]). But more likely he just enjoyed it. If Jimi Hendrix had acid and Keith Richards had Jack Daniels, Prince’s muse was to be found in the carnal.

It wasn’t always subtle. In «Gett Off», for example, he sang: “I like ‘em fat, I like ‘em proud / You gotta have a mother for me / Now move your big ass ‘round this way so I can work on that zipper, baby / ‘Cos tonight you’re a star, and I’m the Big Dipper». Maybe these lyrics should have stayed in his notebook. Bad ideas and good, neat and dirty, they all flowed though his mind, voice and guitar for a 40-year run the likes of which few musicians will ever equal. Musically or sensually, saying no was never his way.

———————————————-

Fans dejan recuerdos en memoria de su ídolo.

Prince, an Artist Who Defied Genre, Is Dead at 57

Jon Pareles – New York Times

Prince, the songwriter, singer, producer, one-man studio band and consummate showman, died on Thursday at his home, Paisley Park, in Chanhassen, Minn. He was 57.

His publicist, Yvette Noel-Schure, confirmed his death but did not report a cause. In a statement, the Carver County sheriff, Jim Olson, said that deputies responded to an emergency call at 9:43 a.m. “When deputies and medical personnel arrived,” he said, “they found an unresponsive adult male in the elevator. Emergency medical workers attempted to provide lifesaving CPR, but were unable to revive the victim. He was pronounced deceased at 10:07 a.m.”

The sheriff’s office said it would continue to investigate his death.

Last week, responding to news reports that Prince’s plane had made an emergency landing because of a health scare, Ms. Noel-Schure said Prince was “fighting the flu.”

Prince was a man bursting with music — a wildly prolific songwriter, a virtuoso on guitars, keyboards and drums and a master architect of funk, rock, R&B and pop, even as his music defied genres. In a career that lasted from the late 1970s until his solo “Piano & a Microphone” tour this year, he was acclaimed as a sex symbol, a musical prodigy and an artist who shaped his career his way, often battling with accepted music-business practices.

“When I first started out in the music industry, I was most concerned with freedom. Freedom to produce, freedom to play all the instruments on my records, freedom to say anything I wanted to,” he said when he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2004. In a tribute to George Harrison that night, Prince went on to play a guitar solo in “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” that left the room floored.

A seven-time Grammy winner, Prince had Top 10 hits like “Little Red Corvette,” “When Doves Cry,” “Let’s Go Crazy,” “Kiss” and “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World”; albums like “Dirty Mind,” “1999” and “Sign O’ the Times” were full-length statements. His songs also became hits for others, among them “Nothing Compares 2 U” for Sinead O’Connor, “Manic Monday” for the Bangles and “I Feel for You” for Chaka Khan. With the1984 film and album “Purple Rain,” he told a fictionalized version of his own story: biracial, gifted, spectacularly ambitious. Its music won him an Academy Award, and the album sold more than 13 million copies in the United States alone.

In a statement, President Obama said, “Few artists have influenced the sound and trajectory of popular music more distinctly, or touched quite so many people with their talent.”

He added, “He was a virtuoso instrumentalist, a brilliant bandleader, and an electrifying performer. ‘A strong spirit transcends rules,’ Prince once said — and nobody’s spirit was stronger, bolder, or more creative.”

A Unifier of Dualities

Prince recorded the great majority of his music entirely on his own, playing every instrument and singing every vocal line. Many of his albums were simply credited, “Produced, arranged, composed and performed by Prince.” Then, performing those songs onstage, he worked as a bandleader in the polished, athletic, ecstatic tradition of James Brown, at once spontaneous and utterly precise, riveting enough to open a Grammy Awards telecast and play the Super Bowl halftime show. He would often follow a full-tilt arena concert with a late-night club show, pouring out even more music.

On Prince’s biggest hits, he sang passionately, affectionately and playfully about sex and seduction. With deep bedroom eyes and a sly, knowing smile, he was one of pop’s ultimate flirts: a sex symbol devoted to romance and pleasure, not power or machismo. Elsewhere in his catalog were songs that addressed social issues and delved into mysticism and science fiction. He made himself a unifier of dualities — racial, sexual, musical, cultural — teasing at them in songs like “Controversy” and transcending them in his career.

He had plenty of eccentricities: his fondness for the color purple, using “U” for “you” and a drawn eye for “I” long before textspeak, his vigilant policing of his music online, his penchant for releasing troves of music at once, his intensely private persona. Yet for musicians and listeners of multiple generations, he was admired well-nigh universally.

Prince’s music had an immediate and lasting influence: among songwriters concocting come-ons, among producers working on dance grooves, among studio experimenters and stage performers. He sang as a soul belter, a rocker, a bluesy ballad singer and a falsetto crooner. His most immediately recognizable (and widely imitated) instrumental style was a particular kind of pinpoint, staccato funk, defined as much by keyboards as by the rhythm section. But that was just one among the many styles he would draw on and blend, from hard rock to psychedelia to electronic music. His music was a cornucopia of ideas: triumphantly, brilliantly kaleidoscopic.

Runaway Success

Prince Rogers Nelson was born in Minneapolis on June 7, 1958, the son of John L. Nelson, a musician whose stage name was Prince Rogers, and Mattie Della Shaw, a jazz singer who had performed with the Prince Rogers Band. They were separated in 1965, and his mother remarried in 1967. Prince spent some time living with each parent and immersed himself in music, teaching himself to play his instruments. “I think you’ll always be able to do what your ear tells you,” he told his high school newspaper, according to the biography “I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became an Icon” (2013) by the critic Touré.

Eventually he ran away, living for some time in the basement of a neighbor whose son, André Anderson, would later record as André Cymone. As high school students they formed a band that would also include Morris Day, later the leader of the Time. In classes, Prince also studied the music business.

He recorded with a Minneapolis band, 94 East, and began working on his own solo recordings. He was still a teenager when he was signed to Warner Bros. Records, in a deal that included full creative control. His first album, “For You” (1978), gained only modest attention. But his second, “Prince” (1979), started with “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” a No. 1 R&B hit that reached No. 11 on the pop charts; the album sold more than a million copies, and for the next two decades Prince albums never failed to reach the Top 100. During the 1980s, nearly all were million-sellers that reached the Top 10.

With his third album, the pointedly titled “Dirty Mind,” Prince moved from typical R&B romance to raunchier, more graphic scenarios; he posed on the cover against a backdrop of bedsprings and added more rock guitar to his music. It was a clear signal that he would not let formats or categories confine him. “Controversy,” in 1981, had Prince taunting, “Am I black or white?/Am I straight or gay?” His audience was broadening; the Rolling Stones chose him as an opening act for part of their tour that year.

Prince grew only more prolific. His next album, “1999,” was a double LP; the video for one of its hit singles, “Little Red Corvette,” became one of the first songs by an African-American musician played in heavy rotation on MTV. He was also writing songs with and producing the female group Vanity 6 and the funk band Morris Day and the Time, which would have a prominent role in “Purple Rain.”

Prince played “the Kid,” escaping an abusive family to pursue rock stardom, in “Purple Rain.” Directed by Albert Magnoli on a budget of $7 million, it was Prince’s film debut and his transformation from stardom to superstardom. With No. 1 hits in “Let’s Go Crazy” and “When Doves Cry,” he at one point in 1984 had the No. 1 album, single and film simultaneously.

He also drew some opposition. “Darling Nikki,” a song on the album that refers to masturbation, shocked Tipper Gore, the wife of Al Gore, who was then a United States senator, when she heard her daughter listening to it, helping lead to the formation of the Parents’ Music Resource Center, which eventually pressured record companies into labeling albums to warn of “explicit content.” Prince himself would later, in a more religious phase, decide not to use profanities onstage, but his songs — like his 2013 single “Breakfast Can Wait” — never renounced carnal delights.

Prince didn’t try to repeat the blockbuster sound of “Purple Rain,” and for a time he withdrew from performing. He toyed with pastoral, psychedelic elements on “Around the World in a Day” in 1985, which included the hit “Raspberry Beret,” and “Parade” in 1986, which was the soundtrack for a movie he wrote and directed, “Under the Cherry Moon,” that was an awkward flop. He also built his studio complex, Paisley Park, in the mid-1980s for a reported $10 million, and in 1989 his “Batman” soundtrack album sold two million copies.

Business Battles

Friction grew in the 1990s between Prince and his label, Warner Bros., over the size of his output and how much music he was determined to release. “Sign O’ the Times,” a monumental 1987 album that addressed politics and religion as well as romance, was a two-LP set, cut back from a triple.

By the mid-1990s, Prince was in open battle with the label, releasing albums as rapidly as he could to finish his contract; quality suffered and so did sales. He appeared with the word “Slave” written on his face, complaining about the terms of his contract, and in 1993 he changed his stage name to an unpronounceable glyph, only returning to Prince in 1996 after the Warner contract ended. He marked the change with a triple album, independently released on his own NPG label: “Emancipation.”

For the next two decades, Prince put out an avalanche of recordings. Hip-hop’s takeover of R&B meant that he was heard far less often on the radio; his last Top 10 hit was “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World,” in 1994. He experimented early with online sales and distribution of his music, but eventually turned against what he saw as technology companies’ exploitation of the musician; instead, he tried other forms of distribution, like giving his 2007 album “Planet Earth” away with copies of The Daily Mail in Britain. His catalog is not available on the streaming service Spotify, and he took extensive legal measures against users of his music on YouTube and elsewhere.

But Prince could always draw and satisfy a live audience, and concerts easily sustained his later career. He was an indefatigable performer: posing, dancing, taking a turn at every instrument, teasing a crowd and then dazzling it. He defied a downpour to play a triumphal “Purple Rain” at the Super Bowl halftime show in 2007, and he headlined the Coachella festival in 2008 for a reported $5 million. A succession of his bands — the Revolution, the New Power Generation, 3rdEyeGirl — were united by their funky momentum and quick reflexes as Prince made every show seem both thoroughly rehearsed and improvisational.

His survivors include a sister, Tyka Nelson, and several half-siblings. His marriages to Mayte Garcia and Manuela Testolini ended in divorce.

A trove of Prince’s recordings remains unreleased, in an archive he called the Vault. Like much of his offstage career, its contents are a closely guarded secret, but it’s likely that there are masterpieces yet to be heard.