Muerte en la tarde

El 2 de julio de 1961, estaba sentado en el aparcamiento de Convair Astronautics en San Diego, escuchando música en la radio del carro mientras mi hermano mayor, Geoffrey, tenía una entrevista de trabajo en la empresa. Nuestro padre había estado trabajando allí, pero había sufrido una crisis nerviosa y estaba hospitalizado. Ahora le tocaba a Geoffrey, recién graduado en Princeton, mantenernos durante los dos meses siguientes, hasta que se trasladara a un puesto de profesor en Turquía y yo comenzara mi nueva vida en un internado de Pensilvania. Acababa de cumplir dieciséis años, con apenas estudios, y Geoffrey se había encargado de prepararme para los rigores académicos de mi nuevo colegio. Además se había postulado para cubrir la vacante dejada por nuestro padre.

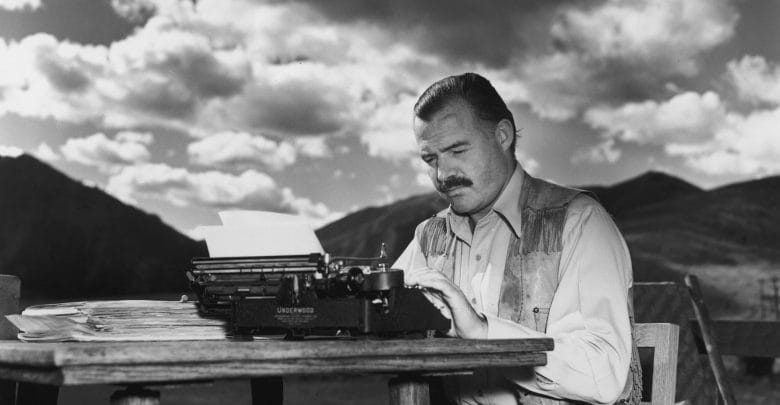

Lo cuento, y lo recuerdo tan vívidamente, porque eso hacía cuando la música se detuvo y en el noticiero radial informaron que Ernest Hemingway se había suicidado. Me habría sido difícil nombrar a muchos escritores vivos, pero Hemingway era lo suficientemente famoso como para que yo hubiera oído hablar de él en la lejanía de las montañas Cascade, en el estado de Washington, donde había vivido los últimos cinco años. Veías fotos suyas en las revistas, en un campamento de caza en África, lanzando un sedal desde su barco en Florida, saliendo del Madison Square Garden después de un combate de boxeo, o simplemente sentado ante su máquina de escribir. Entendías que era importante, un personaje como Winston Churchill, John Wayne o Mickey Mantle.

A pesar de la fama de Hemingway, poca gente conocida mía lo había leído. Yo mismo no había leído mucho, sólo «El viejo y el mar«, que me había regalado la madre de un amigo, y un relato corto, «Los asesinos», que encontré por casualidad en una antología de ficción policíaca. A pesar del título, no mataron a nadie, así que no hubo trabajo detectivesco, pero me llamó la atención el tono ominoso y el diálogo con lenguaje violento de los dos sicarios que esperan al boxeador Ole Andreson en la cafetería, y me desconcertó, me inquietó, la cansada resignación de Ole cuando Nick viene a avisarle. Está claro que este boxeador no va a luchar. No va a triunfar sobre los malos. Se rinde. Y nada se resuelve. Las historias que estaba acostumbrado a leer no terminaban así.

Geoffrey volvió de su entrevista con buenas noticias: le habían contratado. Le respondí con mis propias noticias, sobre Hemingway, y todo el buen humor se borró de su cara. Estaba impactado. Volvimos a casa en silencio. Estaba claro que mi hermano se tomaba esta muerte como algo personal, que realmente estaba afligido. En los días siguientes, encontró un remedio para ese dolor guiándome a través de algunos de los cuentos de Hemingway, un cambio bienvenido frente las tragedias griegas, «Antígona» y «Edipo Rey», que me había hecho estudiar.

Las complejas corrientes subterráneas de los relatos de Hemingway se me escapaban, pero respondía a la sencilla claridad de sus narraciones y a su pura cualidad física: la frialdad de un arroyo, el golpeteo de una estaca de tienda de campaña en el suelo, el olor de la lona dentro de esa tienda, el paso de un anzuelo por el tórax de un saltamontes, el sabor del sirope de una lata de albaricoques o la sensación al arrastrar la mano en el agua desde una canoa en movimiento. Todas estas cosas me resultaban familiares, pero se hacían nuevas gracias a la paciente intensidad de la atención que Hemingway les prestaba. Y fue una especie de revelación que las cosas que me eran familiares pudieran ser materia literaria, incluso un relato de un día en el que no parece ocurrir nada dramático: un hombre se va de excursión, monta un campamento, pesca algo en el río y decide no pescar en el pantano. O que él y un amigo se emborrachan durante una tormenta y hablan de los escritores que les gustan. O cuando rompe con su novia, sin ningún tipo de fuegos artificiales; ella simplemente se sube a una barca y se va remando.

Mi experiencia con Hemingway no concluyó con la tutoría de Geoffrey. Sus relatos y novelas ocupaban un lugar importante en los cursos de inglés de mi nuevo colegio, donde era considerado con algo parecido a una reverencia por parte de los alumnos y los maestros. Recuerdo uno de los intentos del Sr. Patterson de abordar nuestro vicio común de engordar nuestras redacciones con florituras poéticas y cremosas dosis de adverbios y adjetivos vertidos sobre largas frases que vagaban de un lado a otro de la página en busca de una idea, como ratones que intentan encontrar la salida de un laberinto. (¡Florecimiento poético! ¡Metáfora mixta! Cinco puntos menos.) Pensábamos que ese tipo de redacción era literaria, y también nos ayudaba a llegar a la meta del número de páginas requerido. La lectura de nuestras redacciones era, a juzgar por los comentarios cada vez más agrios en los márgenes, una carga para el espíritu del Sr. Patterson. Intentó que editáramos y revisáramos, editáramos y revisáramos, pero nos resistíamos a asesinar a nuestros tesoros literarios. Así que un día, como parte de su proyecto para despertar a nuestros asesinos interiores, el Sr. Patterson nos entregó a cada uno dos páginas fotocopiadas, cada una con un párrafo de prosa de un escritor no identificado. Sólo nos decía que los párrafos estaban tomados de novelas conocidas. «Editen lo escrito«, dijo, y salió de la habitación.

Esto era algo nuevo. Se suponía que debíamos estudiar a los escritores, discernir sus «significados ocultos» y admirar su habilidad para ocultarnos esos significados de forma tan astuta, tan frustrante. Nunca se nos había invitado a editar a un escritor, a corregir a un escritor, como el Sr. Patterson corregía nuestro trabajo, en tinta azul, con su elegante pluma estilográfica.

Uno de los párrafos ocupaba casi toda la página. Al principio trabajé con vacilación, luego con una especie de regocijo blasfemo. Estaba corrigiendo una novela muy conocida. La verdad es que la redacción era terrible -larga, hinchada y torpe- y encontré un nuevo y mezquino placer en castigarla por sus pecados, recortando palabras y frases e incluso oraciones enteras, dividiendo el interminable párrafo en dos. Mi versión final, pensé, era mucho mejor.

Luego pasé al otro texto. Nunca lo había leído, pero sospechaba que era de Hemingway. Hice lo que pude con él, pero en realidad no había nada que editar. Incluso con la licencia que nos había concedido el señor Patterson, y el espíritu agresivo y vengativo que esto había despertado en mí, no me atreví a hacer más que añadir algunas comas, sólo para demostrar que había hecho algo. El texto tenía su propio tono, su propia música, su integridad. No invitaba a retocarlo. Quizás todavía estaba bajo el hechizo de las enseñanzas de mi hermano, su amoroso respeto por la prosa de Hemingway. Tal vez lo esté incluso ahora, porque al día de hoy no alteraría ni una palabra de ese pasaje, que, como nos informó el señor Patterson a su regreso, era el párrafo inicial de «Adiós a las armas«. Leeríamos esa novela más adelante en el año. El otro pasaje era un extracto de algo de James Fenimore Cooper -olvido el título- que no leímos.

Hemingway figuraba no sólo en nuestras clases, sino en nuestras vidas, como el ejemplo de un cierto tipo de hombría. Sabíamos de él que había servido y había sido herido en la Primera Guerra Mundial, y que había presenciado y escrito sobre otras guerras; que había sido un deportista, un cazador de grandes animales y pescador de grandes escualos; un amante del boxeo y de las corridas de toros; y, a juzgar por sus numerosos matrimonios, un amante de las mujeres. Incluso después de su muerte, su presencia era imponente. Intentamos no escribir como él, sabiendo que nos atraparían y se burlarían de nosotros por ello, pero incluso en nuestro rechazo consciente de la influencia reconocíamos el poder singular y contagioso de su estilo. Mi compañero de cuarto y yo desarrollamos una forma de bromas satíricas a la manera de Hemingway; incluso en la parodia le rendíamos homenaje. Nuestros profesores de inglés solían preferir asignar los relatos de Hemingway que sus novelas, ya que los relatos se prestaban más fácilmente a la discusión en clase, donde cada uno podía ser analizado como un todo en el curso de dos o tres días, en lugar de por partes, a lo largo de semanas. Cómo me gustaban esas historias. Me encantaba su exactitud, su pureza de líneas, su confianza en el lector, la misma cualidad de confianza que encontré más tarde en los relatos de Chéjov, Joyce y Katherine Anne Porter. Se dejan cosas importantes sin decir, sí -¿qué hizo Ole Andreson para poner a esos dos asesinos tras su pista? – pero se pueden sentir, intuir, el escritor invita al lector a completar el círculo a partir del arco que se le da, a conspirar con la historia imaginando lo que la precedió, y lo que podría seguir.

He leído los relatos de Hemingway muchas veces a lo largo de los años, se los he dado a mis hijos y los he ofrecido en mis clases, y los mejores siguen estando tan frescos para mí como la primera vez que los leí. En su obra posterior, especialmente en las novelas, podemos ver al Hemingway escritor cediendo a veces al personaje que desarrolló, el personaje al que los chicos aspirábamos: duro, taciturno, conocedor, autosuficiente, superior. Esto podía repercutir en la obra, caricaturizando a sus protagonistas. Pero en los relatos no se encuentra casi nada de eso. De hecho, lo que más me impresiona es su humanidad, su sentimiento de fragilidad humana.

Pienso en Peduzzi, el autoproclamado guía de pesca de «Fuera de temporada«, que se dedica a mendigar bebidas al joven matrimonio al que se ha enganchado, despreciado por sus vecinos, evitado por su propia hija. Se sabe disminuido, pero todavía se permite la dignidad de la alegría, en sus propios términos: «El sol brillaba mientras él bebía. Era maravilloso. Era un gran día, después de todo. Un día maravilloso». Pienso en el viejo viudo de «Un lugar limpio y bien iluminado», que se bebe su soledad, o lo intenta, y en la tierna tolerancia del camarero mayor, que lucha contra su propia soledad y su desesperación. O el joven veterano de guerra Harold Krebs en «El regreso de un soldado», orgulloso de haber sido un buen combatiente, ahora inerte en la casa de su madre, burlándose de su hermana, pidiendo las llaves del coche, comiéndose con los ojos a las chicas del instituto. O Manuel, el torero fracasado de «El invicto«. Todavía recuperándose de una cornada, se apunta a otra corrida. No es un gran torero, pero tiene grandes momentos, y ésa es su tragedia: no puede abandonar una vida que le da esos instantes, pero no tiene los suficientes para prosperar, o, podemos imaginar, para sobrevivir. Incluso después de ser corneado de nuevo, no puede evitar preguntar a un amigo, desde su cama de hospital: «¿No iba yo bien, Manos?». Su sueño lo sostiene, y probablemente lo matará. Hay un humor negro aquí, un humor sin crueldad. El joven Nick Adams, en «Campamento Indio», tras haber presenciado el suicidio de un hombre incapaz de soportar el dolor de su mujer en el parto, se dirige a su casa a través del lago con su padre médico: «A primera hora de la mañana en el lago, sentado en la popa de la barca con su padre remando, se sintió muy seguro de que nunca moriría». Ah. Perfecto.

Robert Frost dijo que la esperanza de un poeta es escribir unos pocos poemas lo suficientemente buenos como para que se interioricen de forma tan profunda que no los podamos sacar. Los relatos de Hemingway se han clavado así de profundo en mí.

Tobias Wolff se graduó en las Universidades de Oxford y Stanford. Enseñó en la Universidad de Syracuse, en Nueva York. Desde 1997 es profesor de literatura en la Universidad de Stanford. Ha conseguido varios premios por sus narraciones, como el «O’Henry», el más importante del país. El libro más reciente de Wolff es «Nuestra historia comienza: Historias nuevas y seleccionadas». Vive en el norte de California.

Traducción: Marcos Villasmil

=============================

NOTA ORIGINAL:

The New Yorker

A Death in the Afternoon

Tobias Wolff

On July 2, 1961, I was sitting in the parking lot at Convair Astronautics in San Diego, listening to music on the car radio while my older brother, Geoffrey, interviewed for a job with the company. Our father had been working there, but had suffered a breakdown and was hospitalized. Now it had fallen on Geoffrey, just graduated from Princeton, to support us for the next couple of months, until he moved on to a teaching post in Turkey and I began my new life at a boarding school in Pennsylvania. I had just turned sixteen and was largely uneducated, and Geoffrey had taken it upon himself to prepare me for the academic rigors of my new school. So he was applying to fill the vacancy left by our father.

I recount this, and remember it so vividly, because that’s where I was when the music stopped and the news came on, and I learned that Ernest Hemingway had killed himself. I would have been hard put to name many living writers, but Hemingway was famous enough that I had heard of him in the remoteness of Washington’s Cascade Mountains, where I’d lived for the past five years. You saw pictures of him in magazines, at a hunting camp in Africa, casting a line from his boat in Florida, leaving Madison Square Garden after a boxing match, or just sitting at his typewriter. You understood that he was important, a figure—like Winston Churchill or John Wayne or Mickey Mantle.

For all Hemingway’s fame, few of the people I knew had actually read him. I hadn’t read much myself, only “The Old Man and the Sea,” which a friend’s mother had given me, and one short story, “The Killers,” which I’d happened upon in an anthology of detective fiction. Despite the title, nobody got killed, so there was no detective work, but I was struck by the ominous tone and the hardboiled dialogue of the two hit men waiting for the boxer Ole Andreson in the diner, and puzzled, unsettled, by Ole’s weary resignation when Nick comes to warn him. It is clear that this fighter isn’t going to fight. He’s not going to triumph over the bad guys. He’s giving up. And nothing is solved. The stories I was used to reading didn’t end this way.

Geoffrey returned from his interview with good news: he’d been hired. I responded with my own news, about Hemingway, and all the high spirits drained from his face. He was shocked. We drove home in silence. It was clear that my brother took this death personally, that indeed he was grieving. In the days that followed, he found a remedy for that grief in leading me through some of Hemingway’s short stories—a welcome change from the Greek tragedies, “Antigone” and “Oedipus Rex,” that he’d had me studying.

The complex undercurrents of Hemingway’s stories eluded me, but I responded to the plain clarity of their narratives, and their sheer physicality: the coldness of a stream; the pounding of a tent stake into the ground; the smell of canvas inside that tent; the threading of a fishhook through a grasshopper’s thorax; the taste of syrup from a can of apricots; or how it felt to trail your hand in the water from a moving canoe. All these things were familiar to me, but were made fresh by the patient intensity of the attention Hemingway brought to them. And it was a sort of revelation that things familiar to me could be the stuff of literature, even an account of a day when nothing dramatic seems to be happening—a man goes on a hike, sets up camp, catches some fish in the river, decides not to fish in the swamp. Or he and a friend get drunk during a storm and talk about writers they like. Or he breaks up with his girlfriend, without any fireworks; she just gets in a boat and rows away.

My experience of Hemingway did not end with Geoffrey’s tutelage. His stories and novels figured importantly in the English courses at my new school, where he was regarded with something like reverence by boys and masters alike. I recall one of Mr. Patterson’s attempts to address our common vice of fattening our essays with poetical flourishes and creamy dollops of adverbs and adjectives poured over long sentences that wandered back and forth over the page in search of an idea, like mice trying to find their way out of a maze. (Poetical flourish! Mixed metaphor! Five points off.) We thought that sort of writing was literary, and it also helped get us to the finish line of the required page count. Reading our essays was, to judge from the increasingly tart comments in the margins, a burden on Mr. Patterson’s spirit. He tried to get us to edit and revise, edit and revise, but we were reluctant to murder our darlings. So, one day, as part of his project to awaken our inner killers, Mr. Patterson handed each of us two xeroxed pages, each bearing a paragraph of prose by an unidentified writer. He would tell us only that the paragraphs were taken from well-known novels. “Edit the writing,” he said, and left the room.

This was something new. We were supposed to study writers, to discern their “hidden meanings” and admire their skill in hiding those meanings so cunningly, so frustratingly, from us. We had never been invited to edit a writer, to correct a writer, as Mr. Patterson corrected our work, in blue ink, with his elegant fountain pen.

One of the paragraphs filled most of the page. I worked hesitantly at first, then with a sort of blasphemous glee. I was correcting a well-known novel! In truth, the writing was terrible—long-winded, bloated, and clunky—and I found a mean new pleasure in punishing it for its sins, slashing out words and phrases and even entire sentences, breaking the interminable paragraph into two. My final version, I thought, was much better.

Then I turned to the other passage. I had never read it before, but I suspected it was from Hemingway. I did my best with it, but really there was nothing necessary to edit. Even with the license Mr. Patterson had granted us, and the aggressive, vengeful spirit this had kindled in me, I could not bring myself to do more than add a few commas, just to show I’d done something. The passage had its own tone—music—integrity. It did not invite tinkering. Perhaps I was still under the spell of my brother’s teaching, his loving respect for Hemingway’s prose. Perhaps I am even now, because to this day I would not alter a word of that passage, which, as Mr. Patterson informed us when he returned, was the opening paragraph of “A Farewell to Arms.” We would read that novel later in the year. The other passage was an excerpt from something by James Fenimore Cooper, I forget the title, which we did not read.

Hemingway figured not only in our classes but in our lives, as the exemplar of a certain kind of manhood. We knew about him: that he had served and been wounded in the First World War, and had witnessed and written about other wars; that he’d been a sportsman, a shooter of big animals and fisher of big fish; a lover of boxing and bullfights; and, judging by his many marriages, a lover of women. Even after his death, he was a commanding presence. We tried not to write like him, knowing we’d be caught out and mocked for it, but even in our conscious disavowal of influence we acknowledged the singular, infectious power of his style. My roommate and I evolved a form of satiric banter in what we took to be the Hemingway manner, even in parody paying homage. Our English masters generally favored assigning Hemingway’s stories over his novels, as the stories lent themselves more easily to classroom discussion, where each could be looked at as a whole in the course of two or three days, rather than in parts, over weeks. How I loved those stories. I loved their exactitude, their purity of line, their trust in the reader—the same quality of trust that I found later in the stories of Chekhov and Joyce and Katherine Anne Porter. Important things are left unsaid, yes—what did Ole Andreson do to put those two killers on his trail?—but they can be felt, intuited, the writer inviting the reader to complete the circle from the arc that is given, to conspire with the story in imagining what preceded it, and what might follow.

I have read Hemingway’s stories many times over the years, given them to my children, and offered them in my classes, and the best of them are still as fresh to me as the first time I read them. In his later work, especially in the novels, we can see Hemingway the writer sometimes yielding to the persona he developed, the persona we boys aspired to: tough, taciturn, knowing, self-sufficient, superior. This could bleed into the work, painting his leading men in caricature. But in the stories you find almost nothing of that. Indeed, I am struck most forcefully by their humanity, their feeling for human fragility.

I think of Peduzzi, the self-appointed fishing guide in “Out of Season,” cadging drinks from the young married couple he’s latched on to, looked down on by his fellow-villagers, avoided by his own daughter. Reduced as he knows himself to be, he is still allowed the dignity of joy, on his own terms: “The sun shone while he drank. It was wonderful. This was a great day, after all. A wonderful day.” I think of the old widower in “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” drinking his loneliness away, or trying to, and the tender forbearance of the older waiter, who is struggling with his own loneliness and despair. Or the young war veteran Harold Krebs in “Soldier’s Home,” proud of having been a good soldier, now inert in his mother’s house, teasing his sister, asking for the car keys, ogling high-school girls. Or Manuel, the failing bullfighter in “The Undefeated.” Still recovering from a goring, he signs up for another bullfight. He is not a great toreador, but he has great moments, and that is his tragedy—he cannot let go of a life that gives him those moments, yet he doesn’t have enough of them to prosper, or, we can imagine, to survive. Even after he’s gored again, he can’t help asking a friend, from his hospital bed, “Wasn’t I going good, Manos?” His dream sustains him, and will probably kill him. There’s a dark humor here, a humor without cruelty. Young Nick Adams, in “Indian Camp,” having witnessed the suicide of a man unable to bear the pain of his wife in labor, is heading home across the lake with his doctor father: “In the early morning on the lake sitting in the stern of the boat with his father rowing, he felt quite sure that he would never die.” Ah. Perfect.

Robert Frost said that the hope of a poet is to write a few poems good enough to get stuck so deep they can’t be pried out again. Hemingway’s stories are stuck that deep in me.