The best kept secret of the Catholic Church—its social teachings

On paper, Catholicism is one of the most progressive faiths in the world: shame about the practice.

On paper, Catholicism is one of the most progressive faiths in the world: shame about the practice.

Sexual abuse, the refusal to ordain women and some high-profile popes: most people would probably cite these things about the Catholic Church—often seen by secular society as a bulwark of conservative religion, especially because of its teachings on sexuality.

But Catholic teachings on social and economic issues are a very important dimension of the Church’s life and have their own long history. Beginning in 1891 with the first social encyclical—Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum (“Of New Things”)—and continuing to Pope Francis’s forthcoming encyclical on ecology, the Catholic Church has developed a significant body of teachings on peace and social justice. These insights have often been in advance of what secular society has been willing to listen to and act on.

However, it’s also true that these insights are sometimes called the Church’s ‘best kept secret’ because there’s such a gap between teaching and practice—between what people hear in the pew in Sunday homilies and the application of these principles to the daily lives of Catholics. Why does this gap exist, and what can be done to close it?

There are four core principles in the Catholic Church’s social teaching: the dignity of the human person, the pursuit of the common good, the value of solidarity, and subsidiarity—the idea that higher decision-making bodies should not restrict lower-level action. Each of these principles have been woven through successive papal encyclicals—official statements of Catholic teachings proclaimed by the pope—and other documents such as those of the Second Vatican Council.

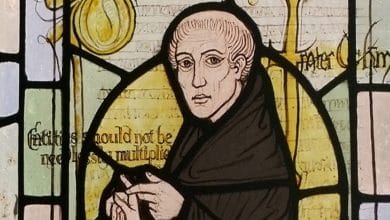

Back in 1891, Rerum Novarum affirmed support for “workers’ associations” like labor unions at a time when this was highly controversial. Forty years later, Pius XI addressed the social issues of the Great Depression in Quadragesimo Anno. He spoke of the need for a “living wage,” sufficient for every family to live in dignity.

During World War II Pius XII spoke out strongly against the war, and his successor John XXIII continued that position in two powerful documents called Pacem in Terris (“Peace on Earth”) and Mater et Magistra (“Mother and Teacher”). The latter laid out principles for world peace (including a cessation of the arms race and the banning of nuclear weapons), and analyzed the conditions that had produced so much economic injustice in the ‘developing’ world.

Pacem in Terris emphasized that relationships between nations must be based on the same values that guide those of communities and individuals: truth, justice, active solidarity and freedom. Catholic social teaching stresses that peace is not simply the absence of war, but is based on the dignity of the person, thus requiring a political order based on justice and charity. The right of conscientious objection is affirmed when civil authorities mandate actions which are contrary to the fundamental rights of the person and the teachings of the Gospel.

In the early 1960s, Vatican II placed the Catholic Church even more squarely in the public sphere: “The joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially of those who are poor or afflicted in any way, are the joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ as well.” The task of the Church is to engage in “reading the signs of the times and interpreting them in the light of the Gospel.”

Populorum Progressio (“On the Progress of Peoples”), Paul VI’s contribution in 1967, did this by asserting that economic development was insufficient unless accompanied by the development of the whole person: the ultimate objective of life is not the pursuit of more material goods. Catholic social teaching rejects the ‘idolatry of the market’ since each person is much more than a producer or a consumer. The birth of liberation theology in the 1960s and its “preferential option for the poor” gave added emphasis to this shift.

Four years later in 1971, a world-wide meeting of Catholic bishops asserted that the promotion of justice lay at the heart of the Church’s life and mission—a theme carried further by John Paul II in his encyclicals on work in 1981 (Laborem Excercens) and the role of the state ten years later (Centisimus Annus), which commemorated the 100th anniversary of Rerum Novarum.

Altogether then, the Catholic Church has over 100 years of progressive social teaching to call on, which raises an obvious question: why hasn’t it put those teachings into practice on a more regular basis?

To answer that question one has to recognise that the Church is a diverse, global body in which congregations and their leaders take up different positions in their own shifting political contexts. For example, some American Catholics were especially angry when Pope John Paul II condemned the US-led war on Iraq in 2003, despite the Church’s teachings on non-violence. Yet in El Salvador in the 1980s and 1990s, the Church—at least in the person of Archbishop Oscar Romero—didn’t hesitate to affirm the primacy of peaceful resistance, and he paid for his courage with his life.

Two issues in particular demonstrate the ways in which Catholic social teachings evolve and are constantly negotiated in this way: gender and the environment.

When it was written in 1963, Pacem in Terris noted that “women are gaining an increasing awareness of their natural dignity.” Vatican II went further to assert that all forms of discrimination—whether based on gender, race, colour, social condition, language or religion—are “to be overcome and eradicated as contrary to God’s intent.” But not until 1988 did the Catholic Church affirm the equal dignity and humanity of women.

In Mulieres Dignitatem issued that year (“On the Dignity and Vocation of Women”), Pope John Paul II wrote that “both man and woman are human beings to an equal degree, both are created in God’s image.” “But we need to create still broader opportunities for a more incisive female presence in the Church” added Pope Francis in his own commentary, Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”) in 2013. This clearly hasn’t yet happened.

The principles are clear, but the praxis lags behind, so the Catholic Church is very far from eradicating sexism and discrimination against women. John Paul II’s preference for a “theology of complementarity” is part of this problem. He emphasized that women and men have ‘complementary’ natures, and thus have different roles in the church and in the family. This is one of the foundations of the Catholic Church’s refusal to ordain women: “complementarity” is often understood to mean that a woman is ‘completed’ by a man.

Sexism and patriarchy permeate every level of Catholic life, and while women now work as theologians and may serve in some diocesan positions, its all-male heads are unable to imagine a Church of shared male-female leadership. Even though the Gospels call people to be servants, not rulers, the fear of losing power is very strong. But sexism distorts the teachings of Jesus by asserting that the male is ‘like unto God.’

A similar evolution is taking place in relation to the environment. The modern ecological movement began in the 1960s with the publication of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring. Catholic leaders were slow to recognize the need to protect the earth, but Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical Caritas in Veritate (issued in 2009) included an important section on ecological issues. He called for “responsible stewardship” over nature and the need for a simpler life-style in rich countries: the Church has a responsibility towards creation which must be asserted in the public sphere.

The direction of Pope Francis’s thinking on these issues is clear. In his inaugural homily on March 19, 2013 he called on all people to be protectors of creation which:

“is not just something involving us Christians alone; it also has a prior dimension which is simply human, involving everyone. It means protecting all creation, the beauty of the created world, as the book of Genesis and as Saint Francis of Assisi showed us. It means respecting each of God’s creatures and respecting the environment in which we live.”

Environmental issues are now important “signs of the time” as anticipated by Vatican II, and Catholics are increasingly involved in eco-justice activities. But there are also climate change denialists in both the pews and among the clergy. Here, lay leadership is crucial: the average Catholic might not know about Pope Francis’s ecological teachings, but she or he does know that the earth is in peril, and that now is the time to act.

The response from Catholics to these developments has been mixed. Surveys of young Catholics indicate that “many young adults are inspired by Catholic social teaching, affirming that this is the dimension of church doctrine with which they must clearly identify.” The adult education program “JustFaith” has helped Catholics to become familiar with new thinking, but conservatives often take exception to any criticism of capitalism and growing inequality. For them, the Church’s teachings on economic justice are not ‘good news.’ So how can new thinking become part of the mainstream of Catholic life?

A few years ago while teaching a course on mysticism and social justice, I discovered that the required course on Catholic social teachings the previous year had addressed only two topics: homosexuality and climate change. It brought home to me the paucity of education on justice issues among clergy and Catholic students. Many priests often don’t get any comprehensive instruction in these teachings during their theological studies.

As a hierarchical institution, stronger leadership in this respect from Catholic Bishops is vital. They need to reassess what themes permeate their teaching: is it mostly sexual ethics with little mention of broader social justice issues?

But Vatican II also emphasized the crucial role of the laity in the Church, and these past fifty years have seen a growth and flourishing of lay leadership all around the world. Many Catholics are eager to learn more about their faith, but not all parishes offer opportunities to do so. Therefore, lay Catholics need to evangelize their priests and parishes in social justice terms as well as the other way around.

Catholics don’t need to wait for the go-ahead from their pastors to engage in works of peace and social justice. That way, the Church’s social teachings won’t be a secret anymore.

Susan Rakoczy is presently on sabbatical at Union Theological Seminary in New York where she is writing a book on feminist interpretations of discernment. She is professor of spirituality at St. Joseph’s Theological Institute and the School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.