TGIF: Kirk Douglas, cien años

En América 2.1, en su sección «Thank God It’s Friday«, dedicada al cine, nos parece justo y necesario ofrecer un pequeño homenaje al ya centenario Kirk Douglas, el último -y muy peculiar- mohicano de su generación, para lo cual ofrecemos algunas muestras de sus películas más emblemáticas, complementadas por una muy completa nota de Anthony Lane, desde 1993 uno de los críticos de cine de The New Yorker.

En América 2.1, en su sección «Thank God It’s Friday«, dedicada al cine, nos parece justo y necesario ofrecer un pequeño homenaje al ya centenario Kirk Douglas, el último -y muy peculiar- mohicano de su generación, para lo cual ofrecemos algunas muestras de sus películas más emblemáticas, complementadas por una muy completa nota de Anthony Lane, desde 1993 uno de los críticos de cine de The New Yorker.

Marcos Villasmil – América 2.1

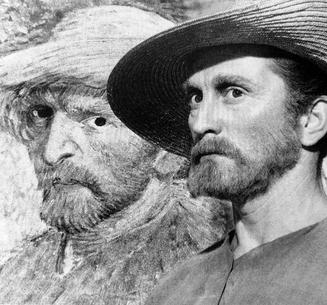

Kirk Douglas como Vincent Van Gogh, en «Lust For Life»

Kirk Douglas cumple cien años

Anthony Lane

Muchas felicidades a Kirk Douglas, que cumple cien años. ¿Cómo se debe celebrar la ocasión? El método más obvio sería saltar con alegría, de remo a remo, a lo largo del flanco de una embarcación; así es como Douglas anunció su regreso a casa en «Los vikingos» (1958), trayéndole muchas alegrías a su pueblo. Si uno pierde el equilibrio y cae al agua, tanto mejor. El problema es que no todos tenemos un fiordo a la mano (la escena puedes verla haciendo clic AQUÍ.)

Tal vez deberíamos ponernos en fila para saludar al gran hombre, como sus colegas hicieron en «The Arrangement« (El Compromiso, 1969), dándole la bienvenida de nuevo a la oficina con un entusiasta apretón de manos y una bandeja con bebidas, pero estén advertidos: esa escena termina con Douglas desplomado en una silla, levantando las manos y diciendo: «Mierda».

Los centenarios del cine son una raza escasa. El último gran nombre en batear las tres cifras fue Bob Hope (1903-2003), y uno no tiene por qué ser admirador de ninguno de los dos para notar la conexión. Un par de fotografías harán el trabajo, lo que confirma que la clave para la longevidad, en Hollywood, no tiene nada que ver con la moral, los matrimonios, los regímenes de ejercicio o los vegetales verdes. Es una cuestión maxilar, tan simple como eso. Tomas aliento, dices una oración, asomas el cuello, y empujas el mentón en su camino a la centena.

La hendidura en la barbilla de Douglas es, con la excepción del Gran Cañón, la grieta natural más popular en los Estados Unidos. La geología del sujeto está abierta a la vista del público, exigiendo reconocimiento; una mirada a ese hoyuelo es suficiente, como una sola sílaba de la voz de Jimmy Stewart. Los fans de los libros de cómic Asterix, que suceden durante la ocupación romana de la Galia, destacarán «Asterix y Obelix – Todo en el mar» (1996), que está dedicado en parte a Douglas, y en la que se dibuja la figura heroica de Spartakis directamente inspirada en él. Lo maravilloso es que en esta versión de dibujos animados, con su rígida cobertura de pelo rubio y su promontórica mandíbula, casi no hay exageración alguna.

(Bueno, aquí están las escenas iniciales de «Lonely are the brave»…más el resto de la película)

Si ello suena improbable, echen un vistazo a los primeros cuarenta segundos de «Lonely are the Brave» (Los valientes andan solos, 1962), y la lista de cosas que la cámara encuentra en su desplazamiento: matorrales desérticos, un fuego que se apaga; a continuación, botas, pantalones de mezclilla, camisa, cigarrillo y la mitad inferior de una cara quemada por el sol. Sabemos quién es. Lo que sigue, por el contrario, nos desconcierta. Douglas se incorpora y mueve el ala del sombrero; entonces se queda mirando hacia el cielo, donde tres aviones dejan estelas de vapor a través de los cielos, tres cicatrices blancas contra un gris profundo, ya que la película es un buen ejemplo del uso del monocromo tardío. ¿Qué demonios está haciendo un vaquero con aviones jets en el cielo? ¿No deberían aparecer más bien flechas, o buitres? Pero ese es el quid de la historia: este hombre es el último de una raza, desafiantemente sin hogar, cortando alambradas bajo el principio de que nadie debe estar encerrado, para luego irse cabalgando. Él ensilla su hermoso caballo palomino, y esperamos ver una pradera abierta, pero él aparece en una nueva cocina luminosa, con todas las comodidades, donde Gena Rowlands le prepara huevos con jamón. Douglas encaja como un payaso en un monasterio. Aún más inquietante es el final de la película, cuando el héroe y su montura son derribados, en una calle lluviosa, por un camión transportando retretes.

«Los valientes andan solos» fue uno de los proyectos favoritos de Douglas, y se puede ver por qué; No sólo porque él ocupaba el centro del escenario ¿dónde más se supone que esté una estrella, por el amor de Dios? sino porque las escenas se extendían desde el viejo al nuevo mundo, y Douglas no era una persona a la que le gustara estar ubicado, y mucho menos confinado, a un único período o lugar. Estaba muy a gusto en el OK Corral, o en la arena romana, vestido con calzoncillos de hierro fundido y con la cota de malla sobre el hombro, pero si lo colocaban en el aquí y ahora mostraba cómo llevar un buen traje como si estuviera blindado. Miremos el amplio traje cruzado que posee en «The bad and the beautiful» (Cautivos del mal, 1952), descendiendo las escaleras para reunirse con Lana Turner, que exhibe un vestido perfecto para la batalla que se anuncia, incluyendo una cubierta de joyas y una nube de piel blanca. Su rugido es como el pinchazo de un tridente. «Tal vez me gusta lucir simple de vez en cuando. Tal vez a todo el mundo le gusta«, le dice, y agrega:» ¿Quién te dio el derecho a invadir mi intimidad, ponerme de revés y decidir cómo soy yo? «Lo que usted diga, señor Douglas.

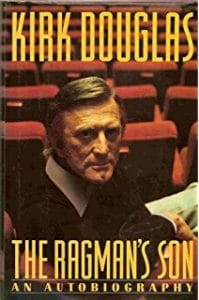

De nombre Issur Danielovitch, nació en Amsterdam, Nueva York. Era toda una familia: tres hermanas, luego el varón, seguido de tres hermanas más. No es de extrañar que su vida rebosara de mujeres. Su padre, Herschel, nacido en Rusia en 1884, había llegado a América hacia 1908; tomó el más inferior de los puestos de trabajo, la recolección de cosas que incluso los pobres habían tirado. De ahí el título de la autobiografía de Douglas, publicada en 1988: «The Ragman’s Son» (El hijo del trapero). Es una lectura agotadora. Todas las peleas y sus repercusiones, los combates de lucha libre, la letanía de conquistas carnales y los problemas contractuales: el carnaval de inmodestia comienza temprano y nunca desaparece. Él recuerda haber escuchado la historia de Abraham e Isaac, y pregunta: «¿Es esa la manera en que Dios debe actuar? ¿No te parece que está tomando ventaja de su posición? ¿No crees que es cruel?» Hay incluso un destello de amenaza en su queja: «Tampoco me gustaba la manera en que Dios trató a Moisés». Esa debe ser la razón por la que Kirk Douglas luce todavía fuerte, a los cien años. Dios debe tener miedo de encontrarse con él.

Los recuerdos de su infancia, a diferencia de algunas de sus anécdotas de la Costa Oeste, lucen creíbles. «Robé comida, al igual que huevos calientes de la gallina del vecino, que abría y tragaba, todo en secreto». Y no olvidemos la caminata de doce cuadras para asistir a la escuela hebrea: «Tenía que ir preparado, ya que cada calle tenía su banda, y siempre estaban esperando para atrapar al muchacho judío». Si ese es el tipo de hematomas con los que creciste, entonces luchar para conseguir que el nombre de Dalton Trumbo -guionista prohibido por la lista negra-, apareciera en los créditos de «Espartaco«, como hizo Douglas, de ninguna manera califica como una batalla.

Luego llegó la señora Livingston. Ella era la maestra de Issur, que introdujo al muchacho en la poesía romántica, tuvo afecto por él, y lo invitó a su casa «para que una noche la ayudara con algunos periódicos ingleses». Byron habría dado su aprobación, aunque asimismo podría haber sugerido que, de vez en cuando Douglas, el Don Juan, le diera descanso a su pluma. El recital de amoríos es inagotable, y sin duda alguna uno sufre una especie de sobresalto histórico al darse cuenta de que hay un hombre -si bien no del todo un caballero- vivo hoy en día que puede informarnos cómo era besarse con Joan Crawford. («Nunca pasamos del vestíbulo,» escribe, «nos quedamos en la alfombra».) Yo prefiero los elegantes eufemismos: «Ann Sothern interpretaba el papel de mi esposa. Ensayamos la relación fuera del escenario«. Cambiaría todas estas revelaciones por el sereno enfrentamiento en «Man without a star» (La pradera sin ley, 1955), cuando Jeanne Crain, cortésmente sentada en un escritorio con un libro de contabilidad abierto delante de ella, le pregunta a Douglas «¿qué quiere usted?«. En respuesta, él toma una pluma, y escribe, subrayándola, la palabra «tú«. Se besan. «Voy a tener un montón de problemas contigo,» dice Douglas, y hace girar la silla de ella, con alegría. «Tiene mucha razón», responde la chica. Los honores quedan igualados. (Veamos la escena):

Lo que surge de las páginas de «El hijo del trapero» es el inconfundible aroma de la certeza. La transformación de Issur Danielovitch en Izzy Demsky y luego en Kirk Douglas parece ordenada, inevitable, y descaradamente sin suerte. Él tenía que suceder. Si su primera película es «El extraño amor de Martha Ivers» (1946) -robándole el papel a Richard Widmark y Montgomery Clift, y con Barbara Stanwyck y Van Heflin en el reparto, entonces es poco probable que haya estado plagado por los demonios de la duda de sí mismo. Los sacude como moscas. Aún más fuerte fue la tercera película de Douglas, «Out of the Past» (Retorno al pasado, 1947), donde interpreta a un gángster al que le gustaría mucho que le devolvieran los cuarenta mil dólares que la chica se llevó. El amor no es tema fundamental. «¿Mis sentimientos? Hace unos diez años los escondí en algún lugar y no he sido capaz de encontrarlos«, admite. Una de las virtudes de Kirk es el brío, extrañamente sin celos, con el que se enfrenta a otros actores; quizá se robe una escena, pero siempre está dispuesto a compartir el botín. En este caso, tenía enfrente a Robert Mitchum. ¿Un cigarrillo?, le pregunta Douglas. «Estoy fumando«, le responde Mitchum, mostrándole lo que ya arde en su mano. Una palabra, un gesto, y listo. Actores que pueden hacer un tiroteo a partir de una caja de Lucky Strikes. Aquí puede verse la breve escena:

El que tanta energía mitificadora se gaste en aquellos que ardieron y se estrellaron en su juventud, de Rodolfo Valentino a Heath Ledger, hace que a veces descuidemos el poder de la larga combustión. Lo desconcertante sobre Douglas es que cuando se revisa su carrera los fuegos artificiales parecen ser una constante. Comenzó en el cine sin prestar atención a sus pisadas, menos aún con el temor tímido de un novato, sino como alguien buscando pelea. ¿Es de extrañar entonces que el público, recién liberado de las fatigas de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, sintiera ese impulso, se adhiriera a él, y se deleitara con la esperanza de su empuje? En el momento en que Douglas interpretó a un boxeador, en «Champion» (El Ídolo de barro, 1949) para la cual se entrenó con un ex-welter llamado Mushy Callahan, su nombre precedió a la pantalla del título, y nos vimos obligados a esperar un rato, viendo solamente su espalda, mientras avanzaba a través de la oscuridad del túnel para luego entrar al resplandor del ring. Por último, se dio vuelta y desplegó su sonrisa. Lo observamos desde abajo, como si ya estuviésemos en la lona y se realizara el conteo. Ni siquiera tuvo que lanzar un puñetazo.

Ah, la sonrisa de Kirk: una de las hojillas con mayor acero en el cine, inoxidable a pesar del paso de los años. Todavía estaba allí cuando se produjo la reunión con su amigo Burt Lancaster, en la ligera pero elegíaca «Tough Guys» (Otra ciudad, otra ley, 1986). Habían actuado juntos muchas veces, comenzando con «I Walk Alone» (Al volver a la vida, 1948); incluso habían cantado y bailado juntos, en la entrega de los premios de la Academia en 1958, con la canción «Es genial no ser nominados.» Lo que los une a ambos -pudiendo ser tres, si añadimos a Charlton Heston- es que, en cada caso, la sonrisa de alguna manera era más aterradora que los rugidos de rabia. El sonriente más implacable de nuestra época es Tom Cruise; sin embargo él se cuida de no renunciar a una atractiva cordialidad, mientras que Douglas y Lancaster, en su esplendor, desnudaban los dientes como lo hacían con las ondulaciones de sus músculos. Si Douglas hubiese interpretado a Quint, en «Tiburón», el tiburón habría virado sus ojos negros y dado marcha atrás, huyendo en la distancia.

No es que Douglas, en sus películas, fuera un simple matón; eso no es garantía de fama. En lo que se refiere al castigo, sus personajes pueden administrarlo, pero el destino tiende a devolverlo y, de hecho, el registro del dolor puede crecer sorprendentemente hasta el punto del masoquismo, como puede dar fe cualquiera que se turbara viendo su actuación como Vincent van Gogh, en «Lust for Life» (El loco del pelo rojo, 1956). El mejor de todos es su Coronel Dax, en «Paths of glory» (Senderos de gloria), estrenada el año siguiente, y dirigida por Stanley Kubrick- «un mierda con talento», en opinión de Douglas. Interpreta a un coronel francés en la Primera Guerra Mundial, con la tarea, en primer lugar, de conducir un ataque infructuoso contra una posición alemana inexpugnable y luego en defensa de sus hombres frente a cargos de cobardía; lo que le sacude no es una descarga de artillería, sino la indiferencia de sus superiores, y lo que le otorga pasión a su actuación es que nunca podemos estar seguros de cuándo y cómo va a perder la sangre fría de militar. Por ello nos desarma una noche mientras descansa en su litera, chaqueta desabrochada, quitándose sus botas. El estado de ánimo es leve. Aparece un sargento de quien Dax sospecha que trata a los rangos inferiores injustamente; y al que a continuación, le ordena, por medio de una amarga lección, que se haga cargo de un pelotón de fusilamiento:

«Usted saca su revólver, camina hacia adelante y dispara una bala en la cabeza de cada hombre.»

«Señor, solicito ser excusado de esta tarea.»

«Solicitud rechazada. Es su deber. Es toda suya.»

Miremos a Douglas, justo antes de que pronuncie la última oración. Todo su ser se tensa; la barbilla es implacable; se hace justicia. ¿Era esa crudeza emocional demasiado para Kubrick, al que le gustaba todo bien cocinado, a la perfección? Fue llamado por Douglas de nuevo, para tomar el timón de «Espartaco«, en 1960, pero Kubrick no volvería a confiar una película a un actor de tan controladora intensidad hasta que Jack Nicholson fue llamado para «The Shining», dos décadas después. Y uno se pregunta, a su vez, cómo le iría, en tiempos como los nuestros, a Douglas y su porte dramático – a la vez magistral y eruptivo, dominando los espacios de una película pero a la vez presa de los dictados de su propio corazón y de sus entrañas -. ¿Podría hoy cualquier actor salirse con la suya, exponiendo la insolencia sublime de Chuck Tatum, el periodista interpretado por Douglas en la película de Billy Wilder «Ace in the hole» (Carta escondida, 1951)? Recién llegado a un tranquilo periódico provincial, enciende una cerilla sosteniéndola contra el cilindro de una máquina de escribir y presionando la tecla de retorno. Más tarde, el mismo truco se repite, pero esta vez otra persona presiona la tecla por Chuck. Él ya tiene el lugar bajo control.

El milagro, en mi opinión, es la cantidad de éxitos de Douglas que no parecen anticuados; es una respuesta completa, de hecho, a la pregunta de qué es un actor protagonista. Ser simpático está muy bien, la credibilidad siempre ayuda, pero ser atractivo a la vista lo es todo: tiene que ser un señuelo para los ojos. Y con esa atracción magnética viene una actitud – el ángulo particular, por así decirlo, en el que un actor se enfrenta al mundo -. En el caso de Douglas, él se inclina hacia delante, como si siempre estuviese agarrando la proa de un barco vikingo, absorbiendo las olas y desarrollando un apetito por la experiencia. «Ahora que has conseguido un gran éxito, te has convertido en un verdadero hijo de puta«, le dijo la columnista de chismes Hedda Hopper, luego de «Champion». A lo que Douglas contestó: «estás equivocada, Hedda. Siempre he sido un hijo de puta. Lo que pasa es que no lo habías notado». La vida es dura, como descubrió Issur Danielovitch, pero si te enfrentas a ella con los puños preparados y con palabras agudas que estén a la misma altura, es posible que alcances la cima. E incluso si no lo logras, al final todavía puedes quedar de pie, luego de haber vivido un centenar de años; ello es una especie de triunfo en sí mismo. El viejo poema dice, «Los caminos de gloria conducen a la tumba.» Todavía no.

Traducción: Marcos Villasmil

NOTA ORIGINAL:

The New Yorker

KIRK DOUGLAS, A HUNDRED YEARS OLD

By Anthony Lane

Many happy returns to Kirk Douglas, who is a hundred years old today. How should the occasion be celebrated? The most obvious method would be to leap joyfully, from oar to oar, along the flank of a longship; that is how Douglas announced his homecoming in “The Vikings” (1958), making the happiest of returns to his people. If you miss your footing and tumble into the water, so much the better. The trouble is that not all of us have a fjord at hand. Maybe we should just line up to greet the great man, as his colleagues did in “The Arrangement” (1969), welcoming him back to the office with an eager handshake and a tray of drinks, but be warned: that scene ends with Douglas slumping into a chair, throwing up his hands, and saying, “Bullshit.”

Centenarians of the cinema are a rare breed. The last big name to hit three figures was Bob Hope (1903-2003), and you don’t need to be an admirer of either man to note the connection. A couple of stills will do the job, confirming that the key to longevity, in Hollywood, has nothing to do with morals, marriages, exercise regimes, or green vegetables. It’s a maxillary matter, as simple as that. You take a breath, say a prayer, stick your neck out, and chin your way to a hundred.

The cleft in the Douglas chin is, with the exception of the Grand Canyon, the most popular natural rift in America. The geology of the guy is open to public view, demanding recognition; one glance at that dimple is enough, like a single syllable of Jimmy Stewart’s voice. Fans of the Asterix comic-strip books, set during the Roman occupation of Gaul, will point you to “Asterix and Obelix All at Sea” (1996), which is dedicated partly to Douglas, and in which the heroic figure of Spartakis is drawn directly from him; what’s wonderful is that this cartoon version, with its stiff hedge of blond hair and its promontory of jaw, is almost no exaggeration at all.

If that sounds improbable, check out the first forty seconds of “Lonely Are the Brave” (1962), and the list of things that the camera finds on its travels: desert scrub, a dying fire, then boots, denims, shirt, cigarette, and the lower half of a sunburned face. We know who this is. What follows, on the other hand, throws us off track. Douglas sits up, tips back the brim of his hat to reveal all, then stares into the sky, where three jets leave vapor trails across the heavens—long white scars against deep gray, since the film is a fine example of late monochrome. What the hell is a cowboy doing with jets overhead? Shouldn’t they be arrows, or circling vultures? But that is the nub of the story: this fellow is the last of a breed, defiantly homeless, snipping wire fences on the principle that nobody should be hemmed in, and riding on through. He saddles his beautiful palomino, and we expect an open prairie, but he winds up in a bright new kitchen, agleam with mod cons, where Gena Rowlands makes him ham and eggs. He fits in like a clown in a monastery. Even more unnerving is the movie’s end, as the hero and his mount are knocked down, on a rainy road, by a truck ferrying toilets.

“Lonely Are the Brave” was one of Douglas’s favorite projects, and you can see why; not just because he was center stage—where else is a star supposed to hang out, for God’s sake?—but because the stage stretched from the old world to the new, and he was not someone who liked to be assigned, let alone confined, to a regular period or place. He was quite at ease in the O.K. Corral, or the Roman arena, clad in cast-iron underpants and on-the-shoulder chain mail, but drop him into the here and now and he would show you how to wear a good suit as if it were armor-plated. Look at the broad double-breasted number that he sports in “The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952), descending the stairs to meet Lana Turner, who has dropped round in full battle-dress, including a floor-length jewelled gown and a cloud of white fur. His snarl is like the jab of a trident. “Maybe I like to be cheap once in a while. Maybe everybody does,” he tells her, and adds, “Who gave you the right to dig into me and turn me inside out and decide what I’m like?” Whatever you say, Mr. Douglas.

He was born Issur Danielovitch, in Amsterdam, New York. It was quite a family: three sisters, then the boy, then three more sisters. No wonder his life thronged with women. His father, Herschel, born in Russia in 1884, had come to American around 1908; he took the lowliest of jobs, gathering stuff that even the poor had thrown away. Hence the title of Douglas’s autobiography, published in 1988: “The Ragman’s Son.” It’s an exhausting read. All the fights and the fallouts, the wrestling bouts, the litany of carnal conquests and contractual flareups: the carnival of immodesty starts early and never subsides. He remembers hearing the story of Abraham and Isaac, and asks, “Is that any way for a God to act? Don’t you think he’s taking advantage of his position? Don’t you think he’s cruel?” There is even a glint of menace in his complaint: “I also didn’t like the way God treated Moses.” So that’s why Kirk Douglas is still going strong, at a hundred. God’s afraid to meet him.

The author’s memories of childhood, unlike a few of his West Coast anecdotes, have the brunt of the believable. “I stole food. I reached under a neighbor’s chicken for the warm egg, cracked it open, swallowed it whole in secret.” And don’t forget the twelve-block walk to Hebrew school: “I had to run the gauntlet, because every street had a gang and they would always be waiting to catch the Jew boy.” If that’s the kind of bruising you grow up with, then struggling to get the name of Dalton Trumbo—banned by the blacklist—into the credits of “Spartacus,” as Douglas did, is hardly a battle at all.

Then there was Mrs. Livingston. She was Issur’s teacher, who introduced the lad to romantic poetry, took a shine to him, and invited him home “to help her with some English papers one evening.” Byron would have approved, although even he might have suggested, now and then, that Douglas the Don Juan pause his pen. The recitation of amours is unflagging, and it certainly gives you a historical shock to realize there is a man—if not quite a gentleman—alive today who can inform you of what it was like to make out with Joan Crawford. (“We never got past the foyer,” he writes. “There we were on the rug.”) I prefer the elegant euphemisms: “Ann Sothern played my wife. We rehearsed the relationship offstage.” And I would trade all such revelations for that poised encounter, in “Man Without a Star” (1955), when Jeanne Crain, seated politely at a desk, with a ledger open in front of her, inquires of Douglas, “What do you want?” In response, he takes a pen, and scratches the word “You” in rough letters across the page. They kiss. “I’m going to have a lot of trouble with you,” he says, and spins her chair around in glee. “You’re so right,” she says. The honors are even.

What rises from the pages of “The Ragman’s Son” is the unmistakable whiff of certainty. The transformation from Issur Danielovitch to Izzy Demsky to Kirk Douglas seems ordained, unavoidable, and brazenly luckless. He had to happen. If your first movie is “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers” (1946)—seeing off Richard Widmark and Montgomery Clift to snag the role, which pairs you with Barbara Stanwyck and Van Heflin—then you are unlikely to be plagued by the demons of self-doubt. You brush them off like flies. Even stronger was Douglas’s third outing, in “Out of the Past” (1947), where he plays a gangster who would very much like his moll back, plus the forty thousand bucks she took with her. Love is not the issue. “My feelings? About ten years ago, I hid them somewhere and haven’t been able to find them,” he admits. One of the virtues of Kirkery is the brio, oddly unjealous, with which he squares off against other actors; stealing a scene, perhaps, but always content to share the loot. In this case, he had Robert Mitchum. “Cigarette?,” one man asks. “Smoking,” the other replies, showing him what already smolders in his hand. A word, a gesture, and they’re done. Actors like this can make a gunfight out of Lucky Strikes.

So much mythologizing energy is expended on those who flamed and crashed in their youth, from Rudolph Valentino to Heath Ledger, that we sometimes neglect the power of the long burn. The bewildering thing about Douglas is that, when you gaze back at his career, it seems to have been fireworks all the way. He entered movies not watching his step, still less with the shy trepidation of a novice, but like somebody spoiling for a fight. Is it any surprise that audiences, freshly released from the toils of the Second World War, should have sensed that momentum, stuck with it, and revelled in the hopefulness of its forward thrust? By the time that Douglas played a boxer, in “Champion,” in 1949 (he trained with an ex-welterweight named Mushy Callahan), his name preceded the title onscreen, and we were forced to wait awhile, viewing him only from behind as he padded through the tunnel’s gloom and entered the glare of the ring. Finally he turned and unleashed the grin. We looked up at him from below, as if we were already down on the canvas and taking the count. He didn’t even have to throw a punch.

Ah, the smile of Kirk: one of the steeliest blades in cinema, unrusted by the years. It was still there when he reunited with his friend Burt Lancaster, in the slight but elegiac “Tough Guys” (1986). They had acted together many times, beginning with “I Walk Alone” (1948); they had even sung and danced together, at the 1958 Academy Awards, performing “It’s Great Not to Be Nominated.” What binds the two of them—and you could make it three, by adding Charlton Heston—is that, in each case, the smile was somehow more frightening than the roars of rage. The most remorseless smiler of our age is Tom Cruise, yet he is careful never to forgo a winning geniality, whereas Douglas and Lancaster, in their pomp, bared their teeth as they did the undulation of their muscles. If Douglas had played Quint, in “Jaws,” the shark would have rolled its black eyes, backed off, and swum away.

Not that Douglas, in his movies, was a mere bully; that is no guarantee of fame. As far as punishment goes, his characters may dish it out, but fate tends to dish it right back, and, indeed, the registration of pain can grow startling to the point of masochism, as anyone who flinched from his Vincent Van Gogh, in “Lust for Life” (1956), can testify. Best of all is his Colonel Dax, in “Paths of Glory,” released the following year, and directed by Stanley Kubrick—“a talented shit,” in Douglas’s opinion. He plays a French colonel in the First World War, tasked first with leading a fruitless attack on an impregnable German position and then with defending his men against charges of cowardice; what shakes him is not an artillery barrage but the indifference of the top brass, and what lends the performance its grip is that you can never be sure when, and how, he will lose his soldierly cool. Thus, he disarms us, one evening, lounging on his bunk, jacket unbuttoned, and tugging off his boots. The mood is mild. In comes a sergeant, whom Dax suspects of treating the lower ranks unfairly, and whom he then orders, by way of a bitter lesson, to take charge of a firing squad:

“You draw your revolver out, you walk forward and put a bullet through each man’s head.”

“Sir, I request that I be excused from this duty.”

“Request denied. You got the job. It’s all yours.”

Look at Douglas, just before he delivers that last line. His whole being tautens; the chin is implacable; justice is served. Was that emotional rawness too much for Kubrick, who liked everything to be cooked just right? He was summoned by Douglas again, to take the helm of “Spartacus,” in 1960, but not until Jack Nicholson was called upon for “The Shining,” two decades on, would Kubrick entrust a film to an actor of such bridling intensity. And you have to wonder, in turn, how Douglas and his dramatic demeanor—at once masterful and eruptive, commanding the space of a movie yet prey to the dictates of his own heart and guts—would fare in times like ours. Could anyone now get away with the sublime insolence of Chuck Tatum, the reporter played by Douglas in Billy Wilder’s “Ace in the Hole” (1951)? Newly landed at a quiet provincial newspaper, he strikes a match by holding it against the cylinder of a typewriter and pressing the carriage return. Later, the same trick is repeated, but this time someone else presses the key on Chuck’s behalf. He has the place in his thrall.

The miracle, by my reckoning, is how much of Douglas’s achievement does notseem dated; how thoroughly it answers, in fact, to a resilient notion of what a leading man is for. Likable is fine, credible always helps, but watchable is everything: he must be a lure to the eyes. And with that magnetic pull comes an attitude—the particular angle, so to speak, at which an actor confronts the world. In Douglas’s case, he leans forward, as if forever grasping the prow of a Viking ship, breasting the waves and building up an appetite for experience. “Now that you’ve got a big hit, you’ve become a real son of a bitch,” the gossip columnist Hedda Hopper said to him, in the wake of “Champion.” To which Douglas replied, “You’re wrong, Hedda. I was always a son of a bitch. You just never noticed before.” Life is hard, as Issur Danielovitch discovered, but if you go at it, fists at the ready, with whetted words to match, you may just come out on top. And even if you don’t, you can still be left standing at the end, a hundred years on; that is a kind of triumph in itself. The old poem says, “The paths of glory lead but to the grave.” Not yet.