Venezuela: Maduro’s muzzle

IN JANUARY Venezuela’s monthly inflation rate entered double-digit territory. Or perhaps not. The claim appeared recently in a tweet from Henrique Capriles, a leader of the opposition. But it is hard to be sure, because the Central Bank has not reported the inflation rate since December. As the economy slumps, shortages spread and inflation rises (in 2014 it was close to 70%), the government has taken to releasing data selectively, if at all. Those for the balance of payments, industrial production and GDP have not been published for six months or more. The closer Venezuela comes to a legislative election that is due to be held sometime this year, the less voters will learn about the state of their country.

IN JANUARY Venezuela’s monthly inflation rate entered double-digit territory. Or perhaps not. The claim appeared recently in a tweet from Henrique Capriles, a leader of the opposition. But it is hard to be sure, because the Central Bank has not reported the inflation rate since December. As the economy slumps, shortages spread and inflation rises (in 2014 it was close to 70%), the government has taken to releasing data selectively, if at all. Those for the balance of payments, industrial production and GDP have not been published for six months or more. The closer Venezuela comes to a legislative election that is due to be held sometime this year, the less voters will learn about the state of their country.

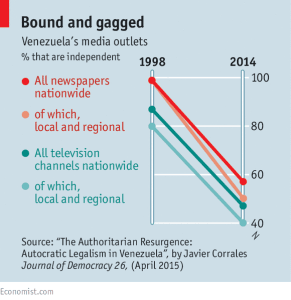

Venezuela’s left-wing “Bolivarian” regime, in power since 1999, has long made life difficult for independent media. In 2007 the government, then led by Hugo Chávez, announced its intention to consolidate its “media hegemony”. It has denied licences to independent radio and television stations, restricted supplies of newsprint, imposed fines on opposition-run media and promoted buy-outs of newspapers and broadcasters by groups with government links. These tactics have worked (see table). Independent outlets reach few people outside the main cities.

Now social media, to which many Venezuelans have turned for news, are under pressure. Seven people were detained last year for what they wrote on Twitter; six remain in jail. On March 26th the chief prosecutor, Luisa Ortega Díaz, said social media should be “regulated” to avoid the spread of rumours.

Under Nicolás Maduro, who succeeded Chávez as president in 2013, the government is supplementing its relentless propaganda with self-censorship. The apparent goal is to hide from Venezuelans bad news that might weaken their already shaky faith in the regime. The health ministry, for instance, has not published a weekly epidemiological bulletin since early November, despite concurrent outbreaks of three mosquito-borne diseases. Last May Venezuela saw its first cases of chikungunya, a disease originating in Africa, which causes very high fevers and severe joint pains. It took the authorities five months to declare chikungunya a notifiable disease. The most recent bulletin still fails to include it.

In November Héctor Rodríguez, the vice-president for social development, gave the total number of cases as 26,451 and said the “growth curve” was “descending”. Independent public-health specialists doubt the figure. They point to a huge rise in cases of “fever”, peaking in October at more than 200,000 a week, seven times the normal number.

At the height of the chikungunya outbreak, doctors in Aragua state, west of Caracas, called for a health emergency to be declared after eight patients with rashes and haemorrhaging died in a regional hospital. Denying any common cause, the government accused the chairman of the local medical association, Ángel Sarmiento, of a “terrorist campaign” and ordered his arrest. Mr Sarmiento fled the country. According to Rafael Orihuela, a former health minister, the deaths were caused by “a severe form of chikungunya”.

Self-censorship is not confined to the health authorities. The National Statistical Institute (INE) has not published poverty data for 2014. No one has provided production figures for PDVSA, the state oil corporation, for the past three months. When officials explain their silence, which is not often, they talk of a need to avoid “political manipulation” of statistics.

Last year Public Space, a human-rights organisation, filed 21 requests for information to various government agencies. Just one, to the budget office, received a reply. Along with other NGOs, Public Space asked the supreme court, which answers to the regime, to compel the health ministry to respond. In August the court’s administrative branch ruled against them. It said requests for information on issues such as the availability of medicines or the workings of the health service “threaten the efficacy and efficiency [of] the public administration”, by obliging bureaucrats to devote time and resources to them. The judges acknowledged that Article 51 of the constitution gives individuals a right to request information and obliges officials to provide it, but proceeded to ignore that.

This week lapatilla.com, a news website, quoted “technical specialists” from the Central Bank, the finance ministry and the INE as accusing these agencies of engaging in “concerted action…to destroy the national statistical system” to disguise the severity of Venezuela’s economic and social crisis. Tamara Herrera, an economist who last June co-signed an open letter urging all three agencies to publish data accurately and on time, says they try to conceal all negative information and “use any achievement as propaganda”. Like every authoritarian ruler, Mr Maduro knows that information is power. He hopes that silence will help him keep it.