Venezuela: The revolution at bay

Mismanagement, corruption and the oil slump are fraying Hugo Chávez’s regime

ON A Wednesday evening around 30 pensioners have gathered for a meeting in a long, brightly lit room in a largely abandoned shopping gallery in Santa Teresa, a rundown and overcrowded district in the centre of Caracas. After a video and some announcements, Alexis Rondón, an official of the Ministry of Social Movements and Communes, begins to speak. “Chávez lives,” he says. “Make no mistake: our revolution is stronger than ever.”

Mr Rondón’s rambling remarks over the next 45 minutes belie that claim. Saying Venezuela is faced with an “economic war”, he calls on his audience to check food queues for outsiders, who might be profiteers or troublemakers, and to draw up a census of the district to identify opposition activists and government supporters. “We must impose harsh controls,” he warns. “This will be a year of struggle”.

About this, at least, Mr Rondón is correct. Sixteen years after Hugo Chávez took power in Venezuela, and two years after he died, his “Bolivarian Revolution” faces the gravest threats yet to its survival. The regime is running out of money to import necessities and pay its debts. There are shortages of basic goods, from milk and flour to shampoo and disposable nappies. Queues, often of several hundred people, form each day outside supermarkets. Ten patients of the University Hospital in Caracas died over the Christmas period because of a shortage of heart valves.

Both debt default and the measures that would be required to avoid one pose risks to the regime. It is on course to lose a parliamentary election later this year, which might then be followed by a referendum to recall Chávez’s inept and unloved successor, Nicolás Maduro. That could bring Venezuela’s revolution to a peaceful and democratic end as early as 2016. But there are darker possibilities. Caracas buzzes with speculation that the armed forces will oust the president.

Venezuela is suffering from the combination of years of mismanagement and corruption, and the collapse in the price of oil, which accounts for almost all of its exports. Chávez, an army officer, was the beneficiary of the greatest oil boom in history. From 2000 to 2012, Venezuela received around $800 billion in oil revenue, or two-and-a-half times as much in real terms as in the previous 13 years. He spent the money on “21st-century socialism”.

Some went on health care and low-cost housing for the poor, who hailed Chávez as a secular saint. Some has gone on infrastructure: a few new roads and metro lines were built, years behind schedule. Another chunk was given away in the form of cheap oil to Cuba and to other Caribbean countries, assuring Chávez loyal allies. Perhaps the biggest slice was frittered away or simply stolen. Filling a 60-litre tank with petrol costs less than a dollar at the strongest official exchange rate. Unsurprisingly, petrol worth $2.2 billion a year, according to an official estimate, is smuggled to Colombia and Brazil, with the complicity of the armed forces.

As well as rewarding supporters with state jobs (the public payroll has more than doubled in 16 years), Chávez expropriated or nationalised 1,200 companies, from steelworks to a maker of cleaning products. Most now lose money and require government loans just to meet their payroll, according to Víctor Álvarez, Chávez’s industry minister in 2005-06. The state subjugates the still-large private sector through price controls, which discourage investment and production. The result is that Venezuela imports much of the food and consumer goods it used to produce, though not enough to meet demand.

Under Mr Maduro the controls have become more draconian. Blaming retailers for the queues outside their shops, this month the government arrested the bosses of a big pharmacy chain and a supermarket company, both of which it has commandeered. Then there is the labyrinth of exchange controls. Until it was modified this month, there were three separate official exchange rates, ranging from 6.30 to the dollar for food and medicines to 50 for many other imports. On the black market, a dollar will buy 180 bolívares. (Since the largest denomination is only 100 bolívares, currency transactions involve fat wads of banknotes.)

This system is an invitation to fraud: the well-connected who are assigned cheap dollars send them abroad or cash them on the black market. Some $20-25 billion was swindled in this way in 2012 alone, according to Jorge Giordani, who as Chávez’s economic guru was the architect of the system. Chavismo’s biggest achievement has perhaps been the creation of a new elite of oil rentiers, dubbed the “Bolibourgeoisie”.

Even before the oil price collapsed, “21st-century socialism” had become unaffordable. Instead of saving windfall oil revenues, as prudence would dictate, the government racked up debt. Between them, the government and PDVSA, the state oil company, issued more debt than any other emerging economy in 2007-11. The fiscal deficit is heading for 20% of GDP this year, according to independent economists.

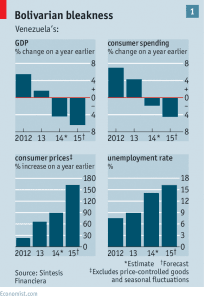

The economy probably contracted by 4% in 2014 and will shrink by more than that this year (see chart 1). In 2013 a third of Venezuelans were living in poverty, up from a quarter the previous year, according to the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Inflation climbed to 64% in the year to November.

Now Venezuela faces a brutal squeeze, if the price of its oil (much of which is heavy and sulphurous) stays at this week’s level of around $50 a barrel. Even if the government slashes imports further, to a bare-bones $35 billion (from $50 billion in 2014), Venezuela will still face an external financing gap of $30.5 billion this year, according to Tamara Herrera of GlobalSource Partners, an economic consultancy.

This includes debt payments by the government and PDVSA adding up to $10.3 billion in 2015. However the central bank’s international reserves total just $21.4 billion. The government has vowed to make a €1 billion ($1.1 billion) debt payment due on March 16th.

Mr Maduro spent most of January travelling abroad seeking emergency loans, without tangible success. In addition to its official reserves, the government may be able to draw on another $20 billion held in opaque funds. On February 10th it announced changes to the foreign-exchange regime that would charge some importers closer to the market rate for dollars. But the change falls short of what is needed to adjust the economy to the scarcity of hard currency. The government may be able to stumble on until October, when debt payments totalling $5 billion start falling due. Barring an increase in the oil price, it will then face a painful choice: default on its debt, which might allow creditors to seize assets, including PDVSA’s foreign refineries, or impose a bigger devaluation and an even tighter import squeeze.

A patrimonial regime

Mr Maduro, a former bus driver, lacks Chávez’s political cunning and popular appeal. His approval rating has plunged to around 20% in opinion polls. He is by nature indecisive, says a source who knows him. But if he has refused to take any of the tough measures required to stabilise the economy it is doubtless because he fears the anger of his own political base if subsidies are withdrawn. His first priority is to shore up his support within the regime.

Superficially, Mr Maduro has been successful. He sidelined several powerful ministers and replaced them with military officers. He has built a loyal political tribe, centred on his own extended family and that of Chávez, according to Margarita López Maya, a sociologist. Many relatives of Mr Maduro’s wife have jobs in the administration. “This is a patrimonial government,” says Ms López Maya.

The authoritarian state he commands is sliding towards totalitarianism. On January 27th the defence minister issued an unconstitutional decree allowing the armed forces to use their weapons against protests if these turn violent. Cuban intelligence agents police the armed forces and the ministries, alert for any sign of dissent. Chávez seized control of the judiciary and all the other constitutionally independent branches of the state. A group of lawyers studied more than 45,000 rulings issued in 2004-13 by the constitutional, administrative and electoral chambers of the supreme court and found that in no case did they rule against the government.

Under Mr Maduro, what the government calls its “media hegemony” is now all but complete. Regime insiders, acting through front men, have bought up opposition media after these were financially weakened by officially promoted advertising boycotts and government refusal to approve the import of newsprint. According to Miguel Henrique Otero, the proprietor of El Nacional, his newspaper is one of only a handful of independent ones that survive. In its case survival has meant shrinking from 1,100 staff in 2008 to 350 now, and cutting the print run from 110,000 copies to fewer than 50,000.

Even as repression increases, the regime is being weakened by internal divisions. Some reform-minded chavistas, like Mr Álvarez, argue that the government should scrap the petrol subsidy, unify the exchange rate and rely on the private sector to reactivate the economy. Others criticise Mr Maduro from the left. Socialist Tide, a university-based group, accuses the government of being corrupt and bureaucratic, and Mr Maduro of betraying Chávez. It is preparing to leave the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV).

Another sign of decay came last month when Leamsy Salazar, a naval captain who for ten years was in charge of Chávez’s personal security, surfaced in the United States. He is reported to have told prosecutors that Diosdado Cabello, the head of the National Assembly who is the regime’s second-most powerful figure, leads a military drug-trafficking “cartel”. Mr Cabello denies the claim and says he will sue.

A rising opposition

An hour out of Caracas, in green rolling country known as Valles del Tuy, Santa Barbara de Dos Lagunas is a rural shantytown, a self-built dormitory settlement of small, roughly finished houses of brick or concrete. In fierce mid-morning sunshine, some 200 residents, most of them women, gather around an awning. They have come to meet Henrique Capriles, their state governor. Mr Capriles leads a centrist faction of the opposition; he narrowly lost a presidential election to Mr Maduro in 2013 (and claims that in fact he won it).

In that election the PSUV won in Dos Lagunas comfortably. Now Mr Capriles, a lean 42-year-old with lively eyes and dark stubble, gets a warm welcome. He hands out vouchers for building materials, promises to repair two sports pitches, and listens to complaints about overflowing sewerage and poor housing. Money is short, he says, and priority must go to the neediest. “The government wants everyone to depend on the state, in order to control them and blackmail them. That’s over.”

Mr Maduro’s strongest card is the opposition’s splits. It is divided among a score of parties and two main currents. The radicals, led by Leopoldo López, a former mayor of a wealthy Caracas district, want to oust Mr Maduro through street demonstrations. They led to months of protests a year ago in which 43 people died. Mr López has been in jail for a year on trumped-up charges—a political prisoner, he says.

Mr Capriles’s strategy is to win a parliamentary election due by the end of this year, and then perhaps trigger a referendum to recall Mr Maduro, which the constitution allows in 2016. Deprived of media exposure Mr Capriles trusts in the retail politics at which he excels. He says change can only come by winning over many disillusioned chavistas, which he now sees as possible. “The country is very different from a year ago,” he says. The two wings of the opposition are drawing closer, with the help of the Catholic church.

Even at the height of Chávez’s popularity, the opposition had the support of one Venezuelan in three. Now polls suggest that twice as many identify themselves as opposition supporters than as chavistas. But many feel alienated from the leaders on both sides.

The PSUV faithful in Santa Teresa repeat the official line that Venezuela is threatened by “the empire” (ie, the United States) and by Colombian paramilitaries. Mr López, the propaganda holds, is a fascist who would strip the poor of everything they have gained. Mr Maduro himself draws a parallel between his government and that of Chile’s Salvador Allende, an elected Marxist toppled by General Pinochet’s CIA-supported coup in 1973.

The parallel is a false one. Allende may have governed badly, but he governed democratically, unlike Chávez or Mr Maduro. It is Venezuela’s opposition who are the democrats, unlike some of those who plotted against Allende. And the United States, apart from a recent congressional initiative to impose sanctions on officials identified as having committed abuses during last year’s protests, has kept well away from Venezuela. A survey by Datanálisis, a polling company, finds that only 22% of respondents still believe the government’s argument that it is the victim of an “economic war”.

If a coup comes it will be because the army decides that Mr Maduro is no longer capable of defending its interests or because hardship prompts the social explosion that is the regime’s deepest fear. The real threat to it may come in the parliamentary election, which on present trends it is all but impossible for it to win. For the first time, chavismo faces the choice between losing an election or resorting to wholesale electoral fraud—or even cancelling the vote in an autogolpe (“self-coup”).

Even a clean election will not settle the question of who will take responsibility for the painful economic adjustment that the regime’s corrupt incompetence has rendered inevitable. There is talk of a church-brokered government of national unity after the parliamentary vote. That would at least increase the chances of a peaceful transition from a failed regime.