Arthur Miller visto por su hija

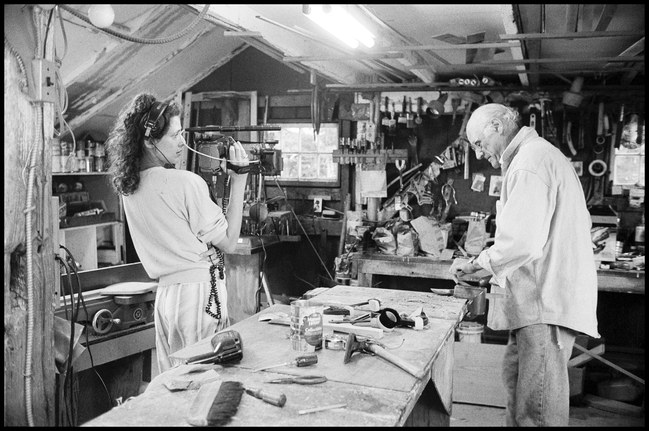

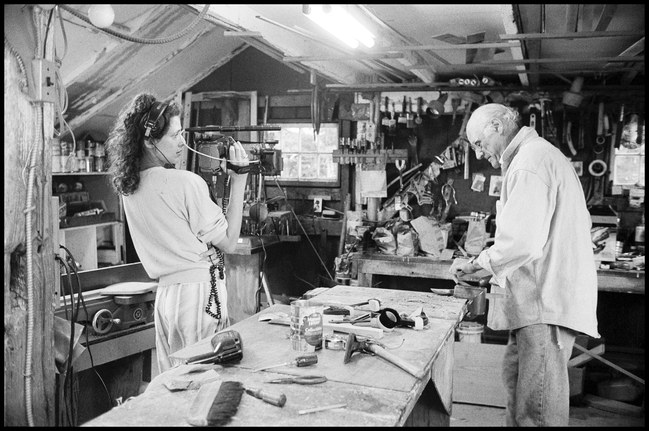

Un nuevo documental de Rebecca Miller ofrece una mirada íntima de la obra teatral de su padre, la lucha contra el Macarthismo y su implacable apetito por el romance. Fotografía de Inge Morath.

«Arthur Miller: escritor«, un nuevo documental de HBO sobre la vida y obra del dramaturgo, fue producido y dirigido por Rebecca, la hija de Miller, quien recopiló material de archivo para dicho proyecto durante más de veinte años. A menudo, era capaz de rodar desde atalayas íntimas o ventajosas: su padre trinchando un pollo recién asado, leyendo el periódico, recogiendo un par de pantalones del suelo para luego ponérselos. «Sentí que yo era el único cineasta que él dejaría acercarse lo suficiente para ver realmente cómo era», nos explica, con una inicial voz en OFF. En conversación, Miller exhibe una inteligencia profunda y una gracia casi preternatural — aprecia tanto la trivialidad como la magnificencia de la vida. Reflexionando sobre sus experiencias, a menudo dice algo casual pero insoportablemente profundo, como «la gente es mucho más difícil de cambiar de lo que yo me había permitido creer». (¡UF!)

Rebecca, quien tiene cincuenta y cinco años, también ha trabajado como cineasta, novelista, y pintora, y está casada con el actor Daniel Day-Lewis. Es hija del tercer matrimonio de Miller, con la fotógrafa austríaca Inge Morath. Las relaciones románticas de su padre ocupan una buena parte de su película. En 1940, Miller se casó con Mary Slattery; en 1951, conoció a Marilyn Monroe. «De repente no fue suficiente para mí,» afirmó Miller sobre su primer matrimonio. Él y Monroe empezaron a intercambiar cartas, que estaban llenas de anhelos. Durante los siguientes cinco años Miller luchó por metabolizar su culpa y su ira: «ya no sabía lo que quería, ciertamente no el final de mi matrimonio, pero la idea de sacar a Marilyn de mi vida era insoportable«, escribe en «Vueltas al Tiempo» («Timebends»), su autobiografía, de 1987. Iba a trabajar cada día al lado de un recorte de tamaño natural de Monroe -la famosa toma de «La picazón del séptimo año«, en la que ella se ríe, su falda blanca ondeando a su alrededor-.

En última instancia, Miller no podía vivir sin ella. Su correspondencia con Monroe creció jadeante, desesperada: «es sólo que creo que realmente debería morir si alguna vez te pierdo», escribió. «Es como si hubiéramos nacido la misma mañana, cuando no existía otra vida en esta tierra». Se casaron en 1956, pero se divorciaron en 1961. Ella murió por una sobredosis de somníferos en 1962. Cuando Miller habla de ella, suena enamorado y derrotado.

Miller se radicalizó en los años cincuenta y, al igual que muchos de sus colegas, fue investigado por el Comité de Actividades Antiamericanas. Finalmente fue declarado culpable de desacato al Congreso, por negarse a proporcionar los nombres de las personas que había visto en las reuniones del partido comunista. «Una especie de fascismo popular se estaba desarrollando en los Estados Unidos«, explica Miller. La debacle nutrió su trabajo (uno tiene la sensación con Miller de que, a la larga, todo nutrió su obra), y en 1953 escribió «Las Brujas de Salem» («The Crucible»), una obra ostensiblemente centrada en los juicios sobre la brujería en Salem. También es una tajante alegoría del Macartismo, y una muestra cruda del tipo de pánico creciente, cegador, que puede atraparnos cuando nos sentimos verdaderamente impotentes.

Miller se casó con Inge Morath en 1962, y estuvieron juntos por los cuarenta años siguientes. Miller estaba para entonces, tal vez, menos obsesionado con el amor. «Te extraño. Estoy desanimado conmigo mismo, con mi desarraigo. Y avergonzado también «, le escribió. «No puedo hablar con nadie más sobre tantas cosas. Me siento obsesionado a veces ante la pregunta de si cualquier cosa, cualquier sentimiento, puede ser eterno». Miller estaba tratando de encontrar el sentido de todo en la escritura. El documental incluye entrevistas conmovedoras y perspicaces con el dramaturgo Tony Kushner — tal vez el único colega real de Miller — y el escritor y director Mike Nichols. Ambos hablan con admiración de la habilidad de Miller para sublimar su propio dolor en su prosa.

La película también aborda, con valentía, el tema de Daniel Miller, hijo de Miller con Morath, que nació con síndrome de Down en 1966, y que fue internado en una clínica poco después. «En ningún momento puse en duda las conclusiones del médico, y estoy sintiendo un brote de amor por mi hijo», escribió Miller en su diario, en 1968. «No me atreví a tocarlo, no fuera que terminase llevándomelo a casa, y lloré.» Aunque Miller no mencionó a Daniel en su autobiografía, él se comprometió con Rebecca a hablar sobre su hijo, pero esa conversación nunca se llevó a cabo. «Tuve la oportunidad de terminar esta película en los años noventa, pero no sabía cómo terminar la película sin hablar de mi hermano, y no sabía cómo hacerlo», explica Rebecca en voz en OFF. «Se lo comenté a mi padre, y se ofreció a hacer una entrevista al respecto. La pospuse. La pospuse por mucho tiempo. Tuve hijos, comencé a hacer otras películas, y él murió».

La película claramente no menciona a la última novia de Miller, la pintora Agnes Barley, que tenía treinta y cuatro años de edad en el momento de la muerte del dramaturgo. Barley conoció a Miller unos meses después de que Morath muriera, en 2002, y ella se mudó a su casa en Roxbury, Connecticut, el mismo año. En una columna de chismes del Daily News, se sugiere que Rebecca y Day-Lewis desaprobaban la relación y su diferencia de edad de más de cincuenta años, y que le pidieron a Barley que dejara la finca de Miller después de su muerte, en 2005. La dinámica precisa de la relación de Miller y Barley sigue siendo confusa — algunas fuentes señalan que estaban comprometidos-.

Pude ver a Miller una vez, brevemente. Él tenía 87 años, y había sido invitado a hablar en un seminario de posgrado al que yo asistía en la Universidad de Columbia, sobre la memoria como una forma de motor literario. (El seminario lo daba la maravillosa poeta Honor Moore, amiga de Miller y vecina en Roxbury.) Estábamos sentados alrededor de una formidable mesa de madera — la misma en la que nos reuníamos para diseccionar nuestras propias historias, intentando olfatear lo que estábamos haciendo mal, y qué (si acaso) estábamos haciendo de forma correcta. Recuerdo sentirme impresionada cuando Miller entró en la habitación. Él había sido parte fundamental o cercana de tantos momentos extraordinarios, y creo que «La Muerte de un Viajante» es uno de los textos norteamericanos más formativos y esenciales. Aunque Miller ya lucía su avanzada edad, habló acerca de la extraña y difícil labor de escribir con tal agudeza y una nitidez que me parecieron deslumbrantes. Parecía que el escritor hubiera descubierto algo.

En 2015, el centenario del nacimiento de Miller, el director belga Ivo van Hove organizó una producción minimalista de «Panorama desde el Puente» en el Teatro Lyceum, en Broadway. Un amigo y yo conseguimos boletos para la noche de estreno. La obra se sitúa en Red Hook, Brooklyn. «Este es el barrio marginal que mira a la bahía en el lado del mar del puente de Brooklyn«, escribe Miller. «Esta es la garganta de Nueva York tragando el tonelaje del mundo.» Si alguna vez ha pasado algún tiempo allí, observando el canal Buttermilk desde la cúspide del muelle Valentino, usted entiende que Red Hook — con su vasto y desolado malecón, con vistas a la Estatua de la Libertad — es un lugar que proporciona una cierta nostalgia.

«Panorama desde el Puente» es una tragedia en el sentido griego. Eddie Carbone, un estibador casado, se enamora de su sobrina huérfana, Catherine. Su situación — como todos los amores furiosos, insuperables, depredadores — está condenada desde el principio y es cada vez más insostenible, ya que Eddie, que está claramente aterrorizado, toma decisiones cada vez más extrañas y terribles. «Su valor proviene en gran parte de su fidelidad al código de su cultura», escribió Miller en 1960, en una introducción a la obra. «De forma invisible, y sin tener que hablar de ello, se estaba preparando para invocar la ira de su tribu sobre sí mismo.»

Miller está interesado en apetitos implacables — uno puede sentir el suyo, en sus cartas a Monroe — y en las maneras en que somos castigados por ellos. La parte del castigo es importante: «en una palabra, yo estaba cansado de la mera simpatía en el teatro», escribió Miller en su introducción a «Panorama desde el Puente.» Requeriría una arrogancia extraordinaria llamar «malo» a Eddie, en el sentido del Día del Juicio, pero, sin embargo, él administra mal su lujuria y envidia, de manera imperdonable. Cuando me encontré sintiendo simpatía hacia él, sentí una enorme vergüenza — Catherine tiene sólo diecisiete años, y piensa en Eddie como en una figura paterna, una confianza que él sistemáticamente mancilla y explota. Sin embargo, su predicamento me recuerda una frase de «La Muerte de un Viajante»: «él no es el mejor personaje que jamás haya vivido», dice Linda Loman de su marido, Willy. «Pero es un ser humano, y le está sucediendo algo terrible. Así que debemos prestarle atención».

La producción de van Hove culmina en un baño de sangre literal: un final salvaje y abstracto. Después, mi compañero y yo nos acercamos a Rudy’s, una taberna irreverente en la Novena Avenida, donde los clientes todavía reciben un perro caliente gratis con cada bebida. No recuerdo lo que discutimos, sólo que masticamos nuestros perros calientes sombríamente. Miller es un experto en destacar la fragilidad humana, tanto dentro como fuera de la familia — todas las formas en que nos traicionamos y nos arruinamos mutuamente. Sus obras a menudo muestran hombres mayores, con defectos, que desconciertan y horrorizan a sus hijos. Ello tiene que ser una de las cosas más terribles que un individuo debe soportar: su propia descendencia mirándolo con decepción. Es devastador contemplarlo en un escenario. «La mejor obra que alguien jamás escribe es aquella que está a punto de avergonzarlo«, afirma Miller en la película. «Siempre. Es inevitable».

«Arthur Miller: escritor» también relata las dificultades de Miller durante los años setenta y ochenta, cuando su obra llegó a ser considerada anticuada — Broadway era ahora demasiado tedioso e irrelevante para importarle a los jóvenes-. «El teatro había perdido su prestigio. La búsqueda de la gente joven en lo que concierne a sus ideas y sentimientos iba en una dirección completamente diferente», explica Miller. De repente el autor estaba enfrentando un momento difícil para poder determinar «el sentido de todo.» En 1968, una pieza del Times sobre su obra «El Precio» puso en duda que Miller estuviera todavía en sintonía con las preocupaciones del momento: «‘ Las Brujas de Salem ‘ ya tiene 15 años. Para una generación que, por lo tanto, no tiene necesidad de asentir respetuosamente ante la mención de Arthur Miller, una obra sobre la responsabilidad humana suena, si no francamente incomprensible, al menos anticuada, «escribió la crítica Joan Barthel.

Miller continuó de todos modos. Escribió veinte obras entre 1968 y 2004. «Yo no percibía que hubiera alguien por ahí interesado. Sentí que estaba gritando en un barril». Sin embargo, ¿qué más podía hacer? Escribir era su trabajo y su propósito. De hecho, el título de la película viene de la respuesta de Miller cuando se le preguntó cuál quería que fuera su obituario. «Escritor», respondió. «Eso debería incluir todo».

Amanda Petrusich es redactora de planta en The New Yorker, y la autora de “Do Not Sell at Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records.”

Traducción: Marcos Villasmil

NOTA ORIGINAL:

The New Yorker

A Daughter’s View of Arthur Miller

Amanda Petrusich

A new documentary by Rebecca Miller offers an intimate look at her father’s work in the theatre, struggle with McCarthyism, and implacable appetite for romance. Photograph by Inge Morath / the Inge Morath Foundation / Magnum / HBO

“Arthur Miller: Writer,” a new HBO documentary about the playwright’s life and work, was produced and directed by Miller’s daughter Rebecca, who collected footage for it for more than twenty years. Often, she was able to shoot from intimate or rarified vantages: her father carving a freshly roasted chicken, reading the newspaper, picking up a pair of bluejeans from the floor and putting them back on. “I felt I was the only filmmaker that he would let close enough to really see what he was like,” she explains, in an early voice-over. In conversation, Miller exhibits deep intelligence and an almost preternatural grace—he appreciates both the inanity and the magnificence of living. While reflecting on his experiences, he will often say something casual but unbearably profound, like “People are far more difficult to change than I had allowed myself to believe.” (Oof.)

Rebecca, who is fifty-five, has also worked as a filmmaker, novelist, and painter, and is married to the actor Daniel Day-Lewis. She is a child of Miller’s third marriage, to the Austrian photographer Inge Morath. Her father’s romantic relationships occupy a good chunk of her movie. In 1940, Miller married Mary Slattery; in 1951, he met Marilyn Monroe. “It wasn’t enough for me, suddenly,” Miller admits of his first marriage. He and Monroe began exchanging letters, which were filled with yearning. For the next five years, Miller struggled to metabolize his guilt and anger: “I no longer knew what I wanted, certainly not the end of my marriage, but the thought of putting Marilyn out of my life was unbearable,” he writes in “Timebends,” his autobiography, from 1987. He went to work each day past a life-size cutout of Monroe—the famous shot from “The Seven Year Itch,” in which she’s laughing, her white skirt billowing up around her.

Ultimately, Miller couldn’t live without her. His correspondence with Monroe grew breathless, desperate: “It is just that I believe that I should really die if I ever lost you,” he wrote. “It is as if we were born the same morning, when no other life existed on this earth.” They were married in 1956, but divorced by 1961. She overdosed on sleeping pills in 1962. When Miller speaks of her, he sounds both enamored and defeated.

Miller was radicalized in the nineteen-fifties, and, like many of his colleagues, he was investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was eventually found guilty of contempt of Congress, for refusing to provide the names of people he had seen at meetings of the Communist Party. “A kind of popular fascism was developing in the United States,” Miller explains. The debacle fed the work (you get the sense, with Miller, that everything eventually fed the work), and, in 1953, he wrote “The Crucible,” a play ostensibly about the Salem witch trials. It’s also a trenchant allegory of McCarthyism and a raw display of the kind of swelling, blinding panic that can seize hold when people feel truly helpless.

Miller married Inge Morath, in 1962, and they were together for the next forty years. Miller was, perhaps, less pie-eyed about love by then. “I miss you. I am discouraged with myself, my rootlessness. And ashamed too,” he wrote to her. “I can’t talk to anyone but you about so many things. I feel haunted sometimes by the question of whether anything, any feeling, is eternal.” Miller was trying to make sense of it all on the page. The film includes poignant and insightful interviews with the playwright Tony Kushner—perhaps Miller’s only real peer—and the writer and director Mike Nichols. Both speak admiringly of Miller’s ability to sublimate his own pain into prose.

The film also bravely addresses Daniel Miller, Miller’s son with Morath, who was born with Down’s syndrome in 1966, and institutionalized shortly thereafter. “I found myself not doubting the doctor’s conclusions, but feeling a welling up of love for him,” Miller wrote in his journal, in 1968. “I dared not touch him, lest I end by taking him home, and I wept.” Though Miller did not mention Daniel in his autobiography, he did agree to speak to Rebecca about him—yet the conversation never happened. “I had the opportunity to finish this film in the nineteen-nineties, but I didn’t know how to finish the film without talking about my brother, and I didn’t know how to do that,” Rebecca explains in a voice-over. “I told my father this, and he offered to do an interview about it. I put it off. I put it off for a long time. I had children, and I started making other films, and he died.”

The film conspicuously doesn’t attend to Miller’s last girlfriend, the painter Agnes Barley, who was thirty-four years old at time of his death. Barley met Miller a few months after Morath died, in 2002, and moved into his Roxbury, Connecticut, home the same year. In a gossip column, the Daily News suggested that Rebecca and Day-Lewis were disapproving of the relationship and its more than fifty-year age difference, and that they asked Barley to leave Miller’s estate following his death, in 2005. The precise dynamic of Miller and Barley’s relationship remains unclear—some sources report they were engaged.

I met Miller once, briefly. He was eighty-seven, and had been invited to speak to a graduate seminar I was taking at Columbia University, on memory as a kind of literary engine. (It was taught by the wonderful poet Honor Moore, Miller’s friend and neighbor in Roxbury.) We were seated around a formidable wooden table—the same one where we gathered to dissect our own stories and attempted to sniff out what we were doing wrong, and what (if anything) we were doing right. I recall feeling awestruck when Miller walked into the room. He had been adjacent or pivotal to so many extraordinary moments, and “Death of a Salesman” is as formative and essential an American text as I can think of. Though Miller looked his age by then, he spoke about the strange and difficult work of writing with a sharpness and acuity that I found staggering. He seemed to have figured something out.

In 2015, the centennial of Miller’s birth, the Belgian director Ivo van Hove staged a minimalist production of “A View from the Bridge” at the Lyceum Theatre, on Broadway. A friend and I got tickets for opening night. The play is set in Red Hook, Brooklyn. “This is the slum that faces the bay on the seaward side of Brooklyn Bridge,” Miller writes. “This is the gullet of New York swallowing the tonnage of the world.” If you have ever spent any time there, considering Buttermilk Channel from the cusp of Valentino Pier, you understand that Red Hook—with its vast and desolate waterfront, overlooking the Statue of Liberty—is a place that accommodates a certain amount of longing.

“A View from the Bridge” is a tragedy in the Greek sense. Eddie Carbone, a married longshoreman, falls in love with his orphaned niece, Catherine. His situation—like all furious, intractable, predatory loves—is doomed from the outset and grows increasingly untenable, as Eddie, who is clearly terrified, makes more strange and awful decisions. “His value is created largely by his fidelity to the code of his culture,” Miller wrote in 1960, in an introduction to the play. “Invisibly, and without having to speak of it, he was getting ready to invoke upon himself the wrath of his tribe.”

Miller is interested in implacable appetites—you can sense his own, in his letters to Monroe—and in the ways in which we are punished for them. The punishment part is important: “In a word, I was tired of mere sympathy in the theater,” Miller wrote in his introduction to “A View from the Bridge.” It would require extraordinary hubris to call Eddie “bad,” in the judgment-day sense, but he nonetheless mismanages his lust and envy in unforgivable ways. Whenever I caught myself feeling sympathetic toward him, I felt enormous shame—Catherine is just seventeen, and thinks of Eddie as a paternal figure, a trust he systematically sullies and exploits. Nonetheless, his predicament reminds me of a line in “Death of a Salesman”: “He’s not the finest character that ever lived,” Linda Loman says of her husband, Willy. “But he’s a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid.”

Van Hove’s production culminated in a literal bloodbath: a wild and abstract finish. Afterward, my companion and I zoomed toward Rudy’s, an ungodly tavern on Ninth Avenue, where patrons still receive a free hot dog with each drink. I do not recall what we discussed, only that we chewed our hot dogs sombrely. Miller is an expert at highlighting human frailty, both within and outside of the family—all of the ways in which we betray and ruin each other. His plays often feature older, failing men, who baffle and horrify their children. This has to be one of the most excruciating things a person can endure: your own child looking at you with disappointment. It’s devastating to behold onstage. “The best work that anybody ever writes is a work that is on the verge of embarrassing him,” Miller says in the film. “Always. It’s inevitable.”

“Arthur Miller: Writer” also recounts Miller’s struggles during the nineteen-seventies and eighties, when his work came to be considered outmoded—Broadway was now too stuffy and irrelevant to matter to young people. “The theatre had lost its prestige. Young folks were looking in an entirely different direction for their ideas and feelings,” Miller explains. He was suddenly having a difficult time ascertaining “the point of it all.” In 1968, a Times piece about his play “The Price” questioned whether Miller was still attuned to the concerns of the day: “ ‘The Crucible’ is already 15 years old. To a generation that has, therefore, no need to nod respectfully at the name of Arthur Miller, a play about human responsibility sounds, if not downright incomprehensible, at least old-fashioned,” the critic Joan Barthel wrote.

Miller kept at it anyway. He wrote twenty plays between 1968 and 2004. “I didn’t feel there was anybody out there who was interested. I felt I was shouting into a barrel,” he says. Still—what else could he do? Writing was his work and his purpose. In fact, the film’s title comes from Miller’s response when asked how he might like his obituary to read. “Writer,” he replied. “That’s all. That should say it.”