Democratic Spring’ stirring in Eurasia?

Meduza journalist Ivan Golunov’s release from house arrest does not imply a softening of the Kremlin’s stance toward civil society or a strengthening of its fight against corruption, Russia analysts suggest. Authorities just a day earlier sentenced well-known activist Leonid Volkov to 15 days in jail for organizing a rally, RFE/RL reports.

“The problem here is that this kind of success as in the case of Golunov is isolated. They don’t accumulate to fundamentally change the system,” Maria Snegovaya, a fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis and a Penn Kemble fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy, told RFE/RL.

Russia would be a democracy, its government accountable to its citizens and the world would not have to contend with its malign influence if its civil society was free, a Capitol Hill meeting heard yesterday.

Russia abuses freedoms in the West, supports brutal dictators in Syria, Venezuela, and Sudan through covert means and suppressed liberty at home, employing a range of measures, from the undesirable organizations law and drastic restrictions on assembly to administrative detention and political prisoners. But this entire machinery of repression has failed, said Miriam Lanskoy, Senior Director for Russia and Eurasia at the National Endowment for Democracy, the Washington-based democracy assistance group.

Russia is changing, she told a forum to launch the Free Russia Foundation’s report detailing the Kremlin’s attempts to influence Western judicial outcomes and its active measures campaigns against liberal democratic institutions.

“We are in a very important moment. Which trend will be faster—the growth of the new, assertive civil society? Or the speed with which Russia clamps down on the internet?,” Lanskoy asked. “The protest wave of 2010-2012 is back, but more broadly spread across the regions and involving more people,” she added, citing protests by truckers, against pension cuts, and the “impressive mobilization” to release Golunov. The best of the lively independent news – investigations, YouTube shows, social media-driven news sites, such as Alexei Navalny’s and Yuri Dud’s Kolyma (below) – get millions of views, up to three times the viewership of state TV news, Lanskoy added.

An incipient Eurasian “democratic spring” may not yet be on the horizon, but political awareness and civil society are gaining ground, analysts suggest.

Recent polls show public trust in President Vladimir Putin has declined to 31 percent, and 45 percent of Russians say their country is going in the wrong direction, a 12-year high, according to RAND’s Denis Corboy, William Courtney, Kenneth Yalowitz. The popular tendency to defer to the center on political decisions also seems to be falling, they add:

These sentiments may be playing out in public protests, such as those across the country last year against raising pension ages, and last month in Yekaterinburg against plans to build a church in a beloved green space which led to its cancellation. Days ago some 7,000 people rallied in the Komi Republic against the “colonial politics” of creating of a landfill in nearby Archangelsk region for garbage from Moscow.

The Free Russia Foundation conference considered effective counter strategies to the Kremlin’s attacks on legal institutions and processes that could be adopted by government agencies, social media platforms and civil society, drawing on the analysis of the report’s authors Ilya Zaslavskiy, Head of Research, Free Russia Foundation (Russia, US), Jakub Janda, Director, European Values Think Tank (the Czech Republic), Martin Vladimirov, Analyst, Center for the Study of Democracy (Bulgaria), John Lough, Associate Fellow, Chatham House (UK) and Neil Barnett, Founder, Istok Associates (UK).

Transparency and accountability in the West, collaboration among allies, and building awareness and resilience are vital, but Internet freedom is fundamental, said the NED’s Lanskoy.

“The Kremlin’s efforts to control the Internet have been clumsy at times but are becoming more ominous,” she said. “Russia successfully installing a Chinese style model of control would be a fundamental and very harmful shift. Supporting internet freedom would mean mobilizing societal awareness and pushback to prevent that possibility.”

But the strategic priority must be supporting Russian civil society and democrats, said Lanskoy, like Natalia Arno and her colleagues at Free Russia Foundation. “If the Russian government became accountable to the Russian people and addressed their interests and priorities, we would not have to confront the Kremlin’s malign influence all over the globe,” she said.

As countries still struggle to overcome an authoritarian Soviet legacy, what does the historical record show? the RAND analysts ask:

- First, countries whose people see themselves as European have made the most democratic progress. Within 13 years of independence Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania met exacting standards to join the European Union and NATO. Most Georgians and Ukrainians see themselves as European, and their countries are gradually developing as democracies and deepening ties with the West. This isn’t to say there’s something quintessentially European about desire for democracy, or vice versa. But the combined allure of European markets and current ideas and practices of accountable government is stimulating vital reforms.

- Second, popular uprisings can help overcome stagnation. Georgia’s Rose revolution in 2003 elevated to the presidency opposition leader Mikheil Saakashvili, who accelerated reforms and Georgia’s path toward Europe before being undone by his own errors. The 2013-14 Maidan revolution led to a government in Kyiv that ably organized resistance to aggression, but voters have judged it did too little to improve living standards or stem corruption. The Velvet revolution in Armenia succeeded through mass mobilization and non-violent tactics. A popular uprising can also yield disappointing results, as with Ukraine’s 2004 Orange revolution.

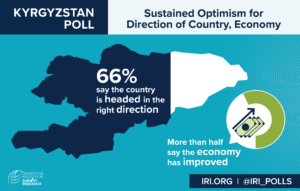

- Third, Central Asian states and Azerbaijan, less immediately tied to the West, have lagged in political development. An exception is

, the only one to have had multiple political transitions through open, contested elections. Increased expression in Kazakhstan and a loosening of controls in Uzbekistan offer hope, but the outlook is clouded. Freedom House classifies all six Central Asian states except Kyrgyzstan as “Not Free (PDF),” a ranking shared also with Belarus and Russia.

, the only one to have had multiple political transitions through open, contested elections. Increased expression in Kazakhstan and a loosening of controls in Uzbekistan offer hope, but the outlook is clouded. Freedom House classifies all six Central Asian states except Kyrgyzstan as “Not Free (PDF),” a ranking shared also with Belarus and Russia. - Fourth, leaders may be more vulnerable if citizens are unhappy with living standards and corruption. Running on these themes, Zelensky beat Poroshenko, who missed the beat by campaigning on “Army, Faith, and Language.” The pension protests in Russia may have been propelled in part by the steady decline in personal incomes in recent years. In Armenia the new government seems aware of the need to improve people’s lives; last February it unveiled a reform program to decrease poverty. Some observers are concerned, however, that Pashinyan is moving too slowly and not promoting reformists.

, the only one to have had multiple political transitions through open, contested elections. Increased expression in Kazakhstan and a loosening of controls in Uzbekistan offer hope, but the outlook is clouded. Freedom House classifies all six Central Asian states except Kyrgyzstan as

, the only one to have had multiple political transitions through open, contested elections. Increased expression in Kazakhstan and a loosening of controls in Uzbekistan offer hope, but the outlook is clouded. Freedom House classifies all six Central Asian states except Kyrgyzstan as