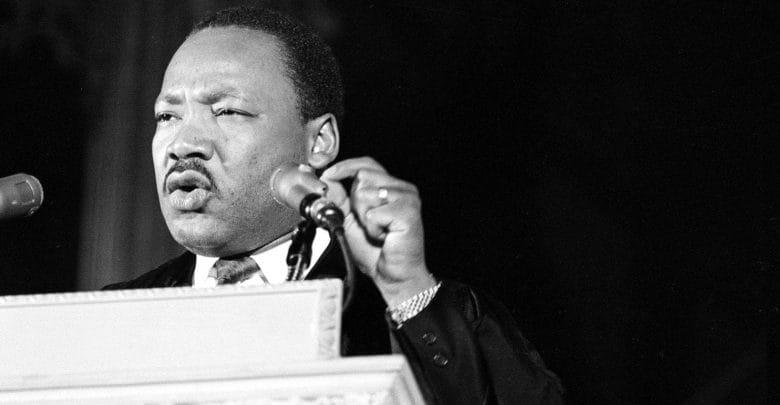

Honramos a Martin Luther King Jr. no por sus victorias, sino por su visión

En el momento de su asesinato en 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. se había convertido en el proverbial profeta sin honor en su propia tierra. Una encuesta hecha por la empresa Harris Poll revelaba que el líder de los derechos civiles de 39 años de edad parecía haber dejado de fascinar la imaginación estadounidense. Tres de cada cuatro encuestados blancos dijeron que desaprobaban las acciones de King después de su oposición a la guerra en Vietnam. Más sorprendente aun, aproximadamente la mitad de todos los estadounidenses negros también lo criticaban.

Sólo unos pocos años antes, King había estado en la cúspide: En 1964, fue el Hombre del Año de la revista Time y la persona más joven hasta la fecha en ganar el Premio Nobel de la Paz. Su éxito en la aprobación de la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1964 fue seguido por la Ley del Derecho al Voto de 1965.

Pero llegó 1968: pocos años después, King era ampliamente criticado, incluso por sus pares en el movimiento de derechos civiles. Los líderes afroamericanos le criticaban que no llevara las protestas a sus ciudades. Ante la actitud de líderes negros como Roy Wilkins de la NAACP y el representante Adam Clayton Powell (D-N.Y.) de Harlem, se lamentaba King: «Su afirmación es… Martin Luther King está muerto; está acabado; su no violencia se ha desvanecido. Nadie lo está escuchando.»

Y de los líderes del creciente movimiento del Poder Negro surgieron otras críticas. La filosofía de protesta pacífica de King era débil y servil; algunos se burlaban de su comportamiento eclesiástico llamándolo irónicamente, a sus espaldas, «De Lawd» («El Señor»). (Incluso en la cúspide de la influencia de King, Malcolm X lo atacaba llamándolo un «Tío Tom moderno«.) Como afirmó un escritor de izquierda sobre el esfuerzo final de King, la Campaña de los Pobres: «El fracaso de la campaña es el beso de la muerte» para la Conferencia del Liderazgo Cristiano del Sur, de King.

El historiador David Garrow dice en su libro «Llevando la Cruz» que los amigos de King comentaban acerca de su abatimiento durante sus últimos meses. «Él era una persona diferente«, destacó el reverendo Ralph Abernathy, aliado incondicional. «Estaba triste y deprimido.»

King llegó a preguntarse si su trabajo estaba teniendo algún impacto y notó la animosidad dirigida a los campeones de las esperanzas insatisfechas. «La amargura es a menudo mayor hacia la persona que construyó la esperanza, que pudo decir: ‘Tengo un sueño’, pero que no podía producir el sueño debido al fracaso y la enfermedad de la nación para responder al sueño».

A menudo hablaba de su propia muerte, que parecía tan cercana y tangible como la mesa de trabajo de cada motel, su atril, o el púlpito. Un domingo en Atlanta, su hogar, reflexionó ante la congregación de la Iglesia Bautista Ebenezer sobre las palabras que esperaba que adornaran su lápida. Unas semanas más tarde, la noche antes de ser asesinado en Memphis, King advirtió a su audiencia que, como Moisés, podría no llegar a la Tierra Prometida.

Sin embargo, una y otra vez en su duro y a menudo solitario camino hacia el martirio, King se reprochaba a sí mismo por la necesidad de permanecer esperanzado. Rendirse a la desesperación que lo atormentaba sería un repudio a todo lo que creía y por lo que vivía. Era su profunda fe cristiana expresándose. Uno puede tener esperanza sin ser cristiano, pero para King, nadie podía ser verdaderamente cristiano sin tener esperanza. Amar a los enemigos, no importa cuán odiosa sea su respuesta, es un acto de optimismo radical y de fe firme. «La esperanza«, afirmaba, «es la negativa final a rendirse».

Este lunes, la nación conmemora los 90 años del nacimiento de King. Las vacaciones de este año nos encuentran a muchos de nosotros en nuestros propios lugares oscuros. El amor por los enemigos es escaso. La solidaridad con los pobres, el forastero, el prisionero, es ampliamente ridiculizada. Las tribus, las sectas y los grupos de identidad exigen lealtad, mientras que se abandona el principio de una humanidad universal y esencial.

En este momento, es bueno recordar que la vida que veneramos y celebramos esta semana fue ensombrecida por la duda, acechada por la división, acosada por el miedo y plagada de un sentimiento de fracaso. Honramos a Martin Luther King Jr. no por sus victorias, que siguen siendo incompletas en el mejor de los casos. Lo honramos por su visión, y por su compromiso sacrificatorio con esa visión. Vio lo que podríamos ser capaces de lograr -como individuos y como nación- y creyó en esa posibilidad tan profundamente que dejó todo lo demás, incluso la vida misma, para mantenerla en alto donde siempre podamos verla.

Como King, también nosotros elegimos cada día si vivimos en la esperanza o en el miedo, con amor u odio, como constructores o destructores. De King, aprendemos la lección de que estas opciones nunca son tan fáciles como suenan y nunca tan populares como nos imaginamos. En King, tenemos un modelo para elegir, y un férreo ejemplo de la negativa final a rendirse.

Traducción: Marcos Villasmil

NOTA ORIGINAL:

The Washington Post

We honor Martin Luther King Jr. not for his victories but for his vision

David von Drehle

At the time of his murder in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. had become the proverbial prophet without honor in his own land. A survey by the Harris Poll found that the 39-year-old civil rights leader appeared to have lost his grip on the American imagination. Three out of 4 white respondents said they disapproved of King’s work after his turn against the war in Vietnam. More striking, roughly half of all black Americans also disapproved.

Only a few years earlier, King had been at a zenith: In 1964, he was Time magazine’s Man of the Year and the youngest person to date to win the Nobel Peace Prize. His success in seeing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 signed into law was followed by the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

But 1968: This scant time later, King was widely criticized, even by his peers in the civil rights movement. African American leaders admonished him not to bring his protests to their cities. Of black leaders such as Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and Rep. Adam Clayton Powell (D-N.Y.) of Harlem, King lamented: “Their point is . . . Martin Luther King is dead; he’s finished; his nonviolence is nothing. No one is listening to it.”

And from leaders of the rising Black Power movement came other criticisms. King’s philosophy of peaceful protest was weak and servile; some derided his churchly bearing by calling him, behind his back, “De Lawd.” (Even at the height of King’s influence, Malcolm X attacked him as a “modern Uncle Tom.”) As one left-wing writer declared of King’s final, underwhelming effort, the Poor People’s Campaign: “The failure of the campaign is the kiss of death” for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Friends of King remarked on his dejection during his last months, historian David Garrow says in “Bearing the Cross.” “He was just a different person,” said stalwart ally the Rev. Ralph Abernathy. “He was sad and depressed.”

King wondered whether his work was having any impact and noted the animosity aimed at champions of unfulfilled hopes. “The bitterness is often greater toward that person who built up the hope, who could say ‘I have a dream,’ but couldn’t produce the dream because of the failure and the sickness of the nation to respond to the dream,” King said.

And he spoke often of his own death, which seemed as close and tangible as his lectern or pulpit or motel worktable. At home one Sunday in Atlanta, he mused to the congregation at Ebenezer Baptist Church about the words he hoped would grace his gravestone. A few weeks later, on the night before he was slain in Memphis, King warned his audience that, like Moses, he might not make it to the Promised Land.

Yet over and over on his hard and often lonely path to martyrdom, King admonished himself to remain hopeful. Surrendering to the despair that haunted him would be a repudiation of all that he believed and lived by. This was his profound Christian faith talking. One can be hopeful without being Christian, but to King, no one could truly be Christian without being hopeful. To love one’s enemies, no matter how hateful they are in return, is an act of radical optimism and steeled faith. “Hope,” he said, “is the final refusal to give up.”

On Monday, the nation commemorates 90 years since King’s birth. This year’s holiday finds many of us in our own dark places. Love for enemies is in short supply. Solidarity with the poor, the stranger, the prisoner, is widely mocked. Tribes, sects and identity groups command loyalty, while the principle of universal and essential humanity goes begging.

At such a time, it is good to remember that the life we revere and celebrate this week was shadowed by doubt, stalked by division, haunted by fear and plagued by a sense of failure. We honor Martin Luther King Jr. not for his victories, which remain incomplete at best. We honor him for his vision, and for his sacrificial commitment to that vision. He saw what we might be capable of — as individuals and as a nation — and believed in that possibility so deeply that he dropped everything else, even life itself, to hold it high where we can always see it.

Like King, we also choose each day whether to live in hope or fear, with love or hate, as builders or destroyers. From King, we learn the lesson that these choices are never as easy as they sound and never as popular as we imagine. In King, we have a model for choosing, and a fierce example of the final refusal to give up.