Book Review: The Presidential Election That America Lost

Richard Nixon campaigns in Philadelphia in September 1968. Credit CSU Archives/Everett Collection

Richard Nixon campaigns in Philadelphia in September 1968. Credit CSU Archives/Everett Collection

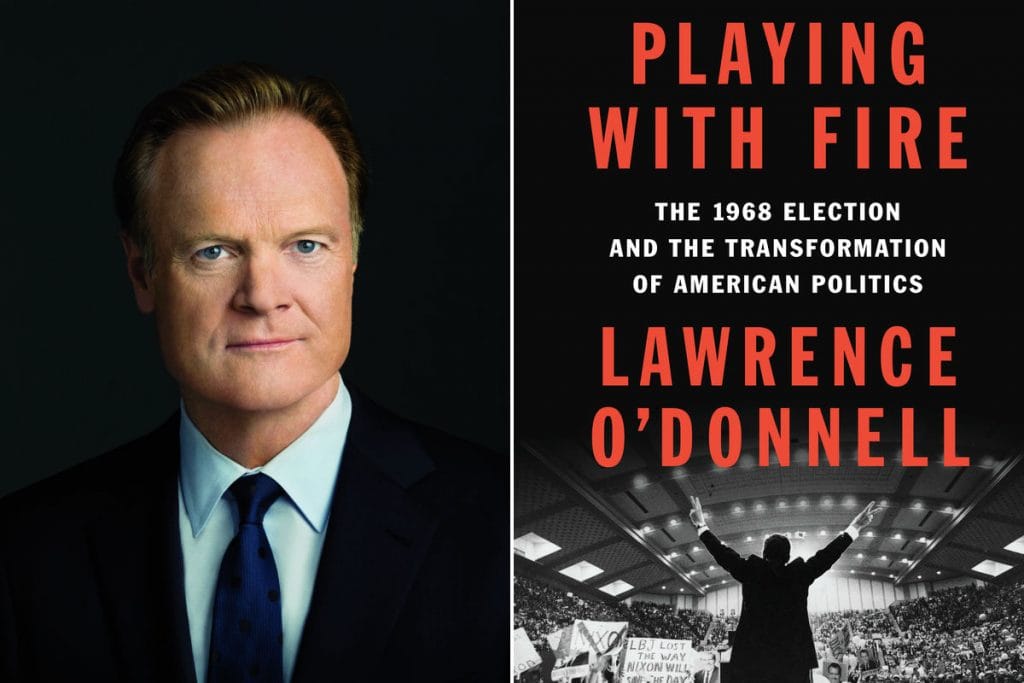

PLAYING WITH FIRE

The 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics

By Lawrence O’Donnell

Illustrated. 484 pp. Penguin Press. $28.

The election of 1968 decided one thing: that Richard M. Nixon and not Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey would become president. It left nearly everything else unresolved. The course of the war in Vietnam, where more than half a million American servicemen were stationed and more than 30,000 had been killed; the fate of the poor in an affluent, but widely unequal, society; the ideological direction of both major political parties; the relationship between the generations and between black and white Americans — all these questions remained open and raw. An election that involved, by the cultural critic John Leonard’s accounting, an “immense expenditure … of money, bombast, blood and cretinism” ended, in effect, in a draw: a narrow victory by the candidate who had disclosed the least about his plans and beliefs, and a nation stuck somewhere along (or maybe off) the path from the old politics to the new. How that all happened is not an unfamiliar story, but it remains, nearly 50 years later, a gripping one.

Lawrence O’Donnell, the host of a political talk show on MSNBC, tells that story with zeal in “Playing With Fire.” O’Donnell was a high school student in 1968, and well remembers the feeling among many young men of draft age that life was “a short-term game.” The presidential election, the young O’Donnell believed, “could end all that.” Viewers of O’Donnell’s show will recognize, in “Playing With Fire,” his faith in the redemptive power of public service — for all its disappointments and foolishness. As a former Senate staffer, O’Donnell takes a practitioner’s delight in the machinations of politics: He finds, and manages to convey, excitement in things like the movement of delegates from one camp to another. As a former producer and writer of the television drama “The West Wing,” he also knows how to pace a story, and could not have dreamed up a more compelling cast of characters. On the Democratic side, in addition to Humphrey, there were Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy, as well as President Lyndon B. Johnson, who left the race in March but then stalked the sidelines, hoping to be called back in. For the Republicans, a trio of governors — Ronald Reagan, Nelson A. Rockefeller and George Romney — threatened Nixon’s ascension. And George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama, ran as an independent and a spoiler. Never in the past century have so many heavyweights contended, all at once, for the White House.

O’Donnell moves briskly and ably through these candidacies, their collisions and a dark bacchanal of events that still defies belief: McCarthy’s messianic yet reluctant crusade to unseat Johnson; Kennedy’s entry into the race; Johnson’s sudden withdrawal, and Kennedy’s assassination the night he won the California primary; Wallace’s provocation of “the common folks” against blacks, elites and “little pinkos”; the frenzy of police batons and tear gas at the Democratic convention in Chicago; and Nixon’s secret flirtation with treason, his effort to “monkey wrench” the president’s attempts to start peace talks, lest a breakthrough in Vietnam benefit Humphrey’s campaign. But “Playing With Fire” is a too-familiar retelling. Over the past decade or two, vast collections of the participants’ papers have been opened, yet O’Donnell has done virtually no original research. Instead he relies heavily on “An American Melodrama,” a masterpiece of eyewitness history written in 1969 by three British reporters, and a handful of other accounts.

O’Donnell’s own observations frequently recall the tossed-off hyperboles of cable news. “In New Hampshire in 1968,” he writes, “the expectations game was born in American politics” — as if McCarthy, who made a surprisingly strong showing in that state’s primary, was the first presidential candidate to gain by outperforming predictions. Similarly, in suggesting that the “crowd intensity” at Wallace rallies exceeded that of any other campaign in American history, O’Donnell overlooks, among other examples, the frenzy that followed William Jennings Bryan across the country in 1896. O’Donnell also asserts that in the 1950s, when Johnson was Senate majority leader, “legislating was child’s play compared to what it became in the 1970s,” an idea belied, in great detail, by Robert Caro’s books on Johnson. It is hard, too, to countenance O’Donnell’s broad claim that in the years after World War II, people never doubted that the president of the United States was the “leader of the free world.”

This is the voice of the pundit, and in a work of history it sounds jarring — all the more so when it’s discussing Donald Trump, as O’Donnell does repeatedly. In the opening chapter, he quips that Trump “should leave a thank-you note at Nelson Rockefeller’s grave … for paving the way in Republican presidential politics for the rich men of Fifth Avenue with complicated marital histories.” O’Donnell goes on to say that “Reagan was the Donald Trump of the 1960s”; that Wallace voters in 1968 “sounded like Trump voters in 2016”; and that Johnson’s crudeness “would not be outdone until Donald Trump moved into the White House.” Some of these parallels are legitimate enough, but they interrupt the narrative and give it, at times, a partisan casting.

O’Donnell’s program on MSNBC is called “The Last Word,” and each night he closes the show with one. His last word in “Playing With Fire” is surprising: “The peace movement won.” He attributes that victory mainly to McCarthy, because “no one did more to stop the killing in Vietnam.” O’Donnell acknowledges that there was a lot more killing ahead — six years’ worth, after Nixon’s election, at a cost of more than 20,000 American lives, and an even greater number of Vietnamese. But he is certain that “if Gene McCarthy had not run for president in 1968, the draft would not have ended in 1973” and the United States would not have withdrawn its troops by 1975. That is a strangely speculative conclusion. It could just as easily be argued that McCarthy, for all the nobility of his cause, actually prolonged the war by widening the divisions among Democrats and helping to elect Nixon — who, upon taking office, began to escalate what he called his “war for peace.” In 1968, America lost.