The latest Iowa poll means more than you might think

On the eve of the 2008 Iowa Democratic caucuses, the Des Moines Register’s poll concluded then-Sen. Barack Obama would win the contest by 7 percent. No other poll was close to that margin; others predicted a near tie or even a big win for Sen. Hillary Clinton. But Obama did win the caucuses ― by 8 percentage points. So when it comes to Iowa polls, the Register poll (now conducted with CNN) has long had a sterling reputation, and on Saturday evening, the latest iteration of that survey was released. Though there’s a long way to go until caucuses night, alarm bells are already sounding for a number of contenders.

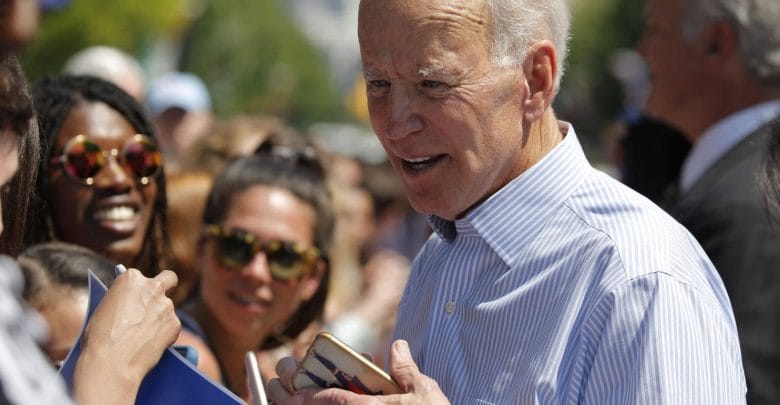

The results, in brief: Former vice president Joe Biden leads the field with 24 percent. (That may not sound like a “lead,” but remember, this is a field with some two dozen candidates.) Below Biden sits a tier of three: Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.) at 16 and 15 percent, respectively, and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg at 14 percent. Next is Sen. Kamala D. Harris (Calif.) at 7 percent. Former Texas congressman Beto O’Rourke and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (Minn.) receive 2 percent each. The other 16 candidates in the poll ― including big names such as Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (N.Y.) ― get 1 percent or less.

What does this tell us about who will win Iowa? Very little. In the past three presidential cycles, voter preferences have always changed markedly between the summer of the prior year and the caucuses themselves (excluding the 2012 Democratic caucuses, the only instance with an incumbent president). Only once has the person running first in Iowa polls the previous summer won on the day of the caucuses. The others ― John Edwards for the Democrats in 2008, Mitt Romney for the Republicans in 2008 and 2012, and Scott Walker for the Republicans in 2016 ― all lost. Even the one winner ― Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Democratic contest ― went from leading her closest rival by nearly 50 points to just a 0.2 percent victory. In short, history argues against betting on Biden.

But the Register’s poll and other recent surveys do tell us a great deal about who has any actual chance at winning Iowa ― and, more important, the party’s nomination. Even this far out, eventual caucuses winners should already be pulling in some support. In the summer of 2007, for example, Obama was pulling in 20 percent in most polls. Mike Huckabee, the 2008 winner on the Republican side, was polling in the mid-single digits at the start of the previous summer, but by August had already jumped to double-digits and continued to rise through the fall. Similarly, in 2016, Donald Trump started the summer (after his relatively late entrance) in the mid-single digits, and by the end of it had vaulted into the lead.

The best hope for the trailers is Rick Santorum in 2012. As late as mid-December 2011, Santorum was still in the mid-single digits; within three weeks, he came from almost out of nowhere to edge out Romney and Ron Paul. But for struggling Democrats, the key word in that last sentence is “almost” ― as other candidates rose and fell in the months leading up to the caucuses, Santorum almost always received a few percent in polls.

So Klobuchar, O’Rourke and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker (who has received 3 to 4 percent in other recent Iowa polls) can take some heart. Biden, Sanders, Warren, Buttigieg and Harris can feel safe (for now). The other 15 or so candidates? Not so much. Winning Iowa isn’t essential, but performing well there is. Aside from 1992, when the rest of the Democratic field ceded Iowa to its junior senator, Tom Harkin, every eventual nominee has either won the state or at least performed creditably. The few who haven’t won have at least gotten a double-digit share of the vote. New rules for the 2020 caucuses ― that candidates must receive at least 15 percent of the overall vote to receive delegates ― make a competitive showing even more important.

Yes, the actual primaries are still months away. But history suggests that for the dozen or so candidates who have barely moved the polling needle, time is already running out. The first Democratic debates could be their last shot.