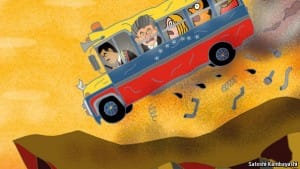

Venezuela’s crisis: Heading for a crash

The president and the opposition are talking to each other. That does not mean they will fix the economy together

The president and the opposition are talking to each other. That does not mean they will fix the economy together

VENEZUELA’S opposition-controlled parliament, the first in nearly 16 years, has been sitting for less than a month. It has been an eventful period. The opposition gained and lost its two-thirds majority; the country’s Supreme Court declared that all its acts would be null and void, then relented. Venezuela’s president, Nicolás Maduro, overhauled his government and seeks new powers to tackle an “economic emergency”. The Central Bank published vital economic indicators for the first time in more than a year. What is not clear is whether all this is leading the country away from an economic and political crash or more rapidly towards one.

Some signs are encouraging. The confrontation between the National Assembly and the Supreme Court ended after three opposition deputies, who had taken their seats in defiance of a ruling by the court, agreed to step aside while an investigation takes place into charges of electoral fraud in their state. This denied the opposition a two-thirds majority, but allowed the regime to recognise parliament’s legitimacy. On January 15th Mr Maduro, a former bus driver, delivered his state of the union speech before a hostile legislature for the first time. The mocking rebuttal by Henry Ramos Allup, parliament’s new president, was broadcast live—another first.

Some of Mr Maduro’s recent decisions suggest openness to dialogue. One is the appointment of Aristóbulo Istúriz, a former mayor of Caracas, to be the country’s vice-president. He replaces Jorge Arreaza, the son-in-law of the late Hugo Chávez, the founder of Venezuela’s failing “Bolivarian revolution”. Unlike Mr Arreaza, the new vice-president is respected both by the opposition and within chavismo. Mr Ramos has spoken to Mr Istúriz at least twice. Their conversations helped end the standoff between parliament and the Supreme Court. Mr Ramos expects Mr Istúriz to be a “facilitator” of communication.

Whether talking will lead to useful action is uncertain. On January 15th the Central Bank partly owned up to the dire state of the economy. It said that in the 12 months to September inflation was 141.5% while GDP shrank by 7.1% over the same period. Even those numbers probably understate the awfulness. The IMF reckons the economy shrank by 10% last year and that inflation is now over 200%.

Why inflation is a conspiracy

There is little sign that president and parliament agree on why things are so bad—apart from the collapse in the price of oil, virtually the only export—or what to do about it. In his three-hour speech Mr Maduro once again blamed shortages, inflation and a weak currency on an “economic war” waged by speculators and foreigners. Mr Ramos retorted, with more accuracy, that “the economic model is wrong.”

Mr Maduro’s economic emergency decree would give him sweeping powers over the economy for 60 days. That could be dangerous. In shaking up his cabinet Mr Maduro gave the job of economic tsar to Luis Salas, a sociologist who comes from the far-left fringes of chavismo. He regards inflation as a capitalist conspiracy against consumers and denies that the Central Bank helps cause it by printing money to finance the budget deficit. Other members of the new economic team, including Rodolfo Medina, the finance minister, and Miguel Pérez Abad, who brings a business background to the industry ministry, are more moderate. But it is not clear how much influence they will have.

Mr Maduro admitted that “the time has come” to raise the price of petrol, which is virtually given away. That is a big reason for the government deficit, which was 24% of GDP last year. Beyond that, it is not clear how he would use the new powers he is asking parliament to grant him. The proposals drawn up by Mr Salas urge businesses to increase production, but without lifting price controls or suggesting a way to raise imports of supplies. There will be no cuts to social spending.

Some in the opposition suspect the government is laying a trap. If the assembly rejects Mr Maduro’s plan, it risks being accused of denying protection to popular social programmes. If it accepts, it will renounce its power to intervene in the economy. Parliament had still not decided when The Economist went to press.

Other issues could yet refreeze relations between the legislature and the government. The opposition plans to pass an amnesty law to free scores of political prisoners, which Mr Maduro has already vowed to reject. Mr Ramos has not retreated from his promise to remove the president by constitutional means within six months. A crack-up will be hard to avoid.