Baseball is almost like oxygen for Willie Mays. He spent a month this year with his old team, the San Francisco Giants, at spring training in Scottsdale, Ariz., where baseball’s greatest living player served as unofficial clubhouse greeter. In normal times, Mays would now be a regular presence at the Giants’ home games, sharing stories and laughs.

“Baseball is his whole outlet, his way to express himself,” said John Shea, co-author of Mays’s new book, “24: Life Stories and Lessons From the Say Hey Kid” and a longtime baseball writer for The San Francisco Chronicle. “He doesn’t have access to all the players and the people for that taste of baseball, which he just lives for.”

Mays turned 89 last week, and he is homebound in Atherton, Calif., because of the coronavirus pandemic. He lives with a personal assistant and a friend who was the caretaker for Mays’s wife, Mae, before she died in 2013 after a long fight with Alzheimer’s disease. Trusted friends like Shea can come see him, but the daily give-and-take at the ballpark is missing.

“My thing is keep talking and keep moving,” Mays told Shea the other day, but those activities are complicated. Mays reads body language the way he once tracked fly balls, so in-person interviews are the only kind he can comfortably give. He took questions through Shea for this column, as the constraints of the day have curtailed what should be a celebratory publicity push for his book.

Mays has collaborated on books before, but “24” feels like a valedictory address in which the speaker is too humble to brag, but waves of guests take the stage to give stirring testimony. Shea presents Mays’s words in bold, letting him steer the narrative before Shea’s extensive reporting fills in the gaps.

Shea first proposed the idea some 15 years ago to Mays, who envisioned the book as something to be taught in classrooms. Shea collected anecdotes from several important figures who have since died, including Mays’s former Giants teammates Willie McCovey, Alvin Dark and Johnny Antonelli and the former Giants owner Peter Magowan. He also interviewed opponents, historians, current stars like the Angels’ Mike Trout and the former presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

“I found out with both Bush and Clinton, their childhood heroes were Willie Mays,” Shea said. “Bush told me that he didn’t want to be a president, he wanted to be Willie Mays.”

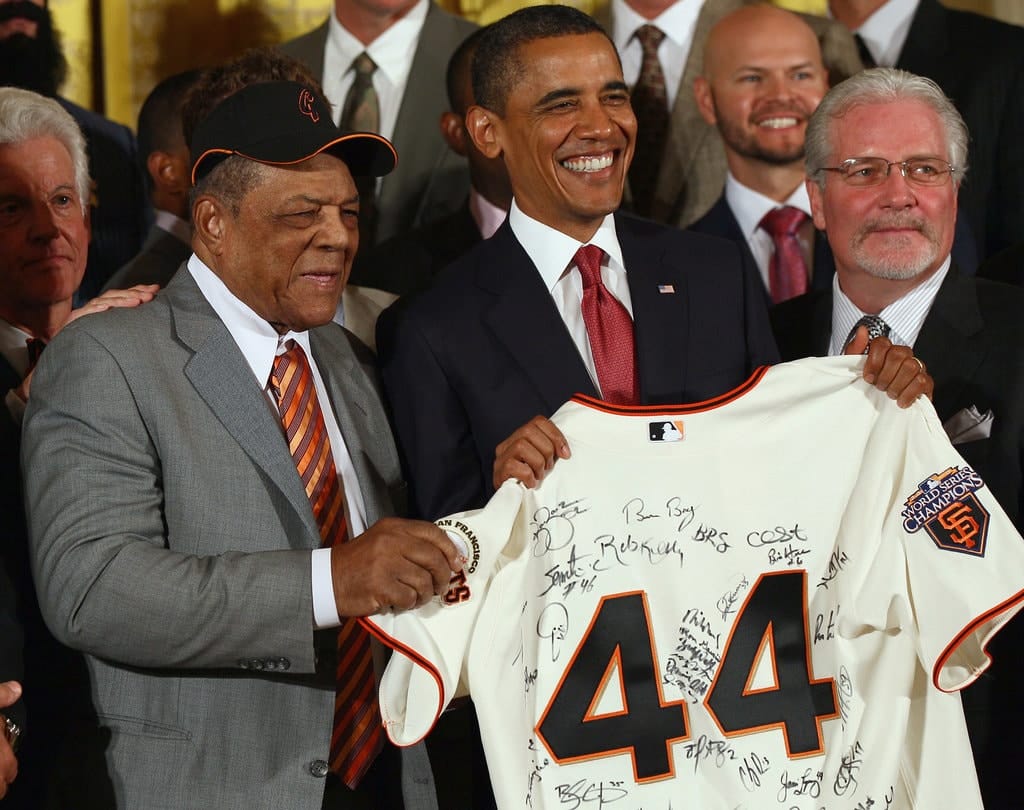

Mays is also close to former President Barack Obama, who flew with Mays to an All-Star Game on Air Force One, gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 and is the subject of a full chapter in “24.” Mays says in the book that he was scared while watching Obama’s victory speech after the 2008 election, because he feared an assassination.

Mays does not dwell on the racism he experienced in his career, before and after stardom: He was taunted as a minor leaguer in Trenton, N.J., and initially turned down for a home he wanted to buy in San Francisco because of his race. Mays never comes across as bitter, even though he was also discounted as a young player despite talent that colorblind scouting could not possibly have overlooked.

The Boston Red Sox had a farm team that shared Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Ala., with the Black Barons, Mays’s team as a teenager in the Negro Leagues. Yet the Red Sox passed on Mays, who signed in 1950 with a New York Giants scout, Eddie Montague, for $4,000 and a monthly salary of $250, with the Barons getting $10,000. The Red Sox became the last major league team to integrate, with Pumpsie Green in 1959.

“Oh, they had me easy,” Mays said of the Red Sox as he talked with Shea for this column. He added later that it had all worked out for the best: “I didn’t like the ballparks in the American League. I thought the National League was stronger than the American League. That’s what I thought.

“When I went to the All-Star Game over there” — in 1961 — “they wanted me to say that I wanted to be a Red Sock. I said, ‘No, I’ll go where they paid my family.’”

Mays shares the record, with Hank Aaron and Stan Musial, for most All-Star Games — 24, naturally — and the book conveys how seriously he embraced his role as an entertainer. Mays would go out of his way to thrill, making easy plays look difficult, or baiting a runner by slowly pursuing a ball and then firing a strike to nail him at the plate.

“I had to go way around in my mind, but I could get him,” Mays said. “People said, ‘How the hell can you do that?’ I don’t know. I just saw him running home rather than running to second.”

We will never know what might have happened if Mays himself had been running from first on the double he hit in Game 7 of the 1962 World Series with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning. With San Francisco trailing by 1-0 and the Yankees’ Ralph Terry on the mound, Mays lashed a double to right that slowed on the wet grass. Matty Alou was running from first and stopped at third, setting up McCovey’s game-ending liner. Mays has always pictured a different outcome.

“If it had been me, they would’ve had to throw me out coming home,” Mays said. “I would’ve tried for home. Matty slowed down when he got to third. There’s no way I would’ve stayed on third. There were two outs.”

Eleven years later, across the bay in Oakland, Mays had another chance to come up as the potential final out of a World Series Game 7, this time as a member of the Mets against the A’s. After a two-out error in the ninth, Oakland removed Rollie Fingers for the left-handed Darold Knowles, with the left-handed Wayne Garrett coming up as the tying run. Mays hit right-handed, of course, but Manager Yogi Berra left him on the bench. Garrett popped out, and Mays never played again.

“I kick myself,” Mays says in the book. “I could’ve gone to Yogi and said, ‘I’ve got to pinch-hit, man.’ I think he would’ve said, ‘OK, go ahead and pinch-hit.’ I think that’s what he would have said, because we had that type of relationship. But I said, ‘No, that’s not how to do it.’ I never did that.”

Mays’s final hit was a go-ahead, extra-inning single in Game 2 of that World Series, though the lasting image of the end of his career is his fall in center field while battling the sun. It was a striking contrast to his indelible catch at the Polo Grounds in 1954, a moment preserved in a statuette now given annually, in his name, to the most valuable player in the World Series.

The 2020 World Series is in jeopardy now, like the season itself, another American standby threatened by the pandemic. As we wait, Mays’s life story makes a compelling quarantine read. He could have gone a bit deeper — especially about his godson, Barry Bonds, the home run king tainted by links to performance-enhancing drugs — but controversy is not Mays’s style.

He is still a crowd-pleaser at 89, forever symbolizing the “combination of greatness and joy,” as Clinton says, that explains so much about the allure of sports. His new memoir will remind fans of why we love baseball so much, and also, now, of why we miss it.

Tyler Kepner has been national baseball writer since 2010. He joined The Times in 2000 and covered the Mets for two seasons, then covered the Yankees from 2002 to 2009.