Yemen crisis: Why is there a war?

Yemen, one of the Arab world's poorest countries, has been devastated by a civil war. Here we explain what is fuelling the fighting, and who is involved.

How did the war start?

The conflict has its roots in the failure of a political transition supposed to bring stability to Yemen following an Arab Spring uprising that forced its longtime authoritarian president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, to hand over power to his deputy, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, in 2011.

As president, Mr Hadi struggled to deal with a variety of problems, including attacks by jihadists, a separatist movement in the south, the continuing loyalty of security personnel to Saleh, as well as corruption, unemployment and food insecurity.

Ali Abdullah Saleh (R) was forced to hand over power to Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi (L)

Ali Abdullah Saleh (R) was forced to hand over power to Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi (L)

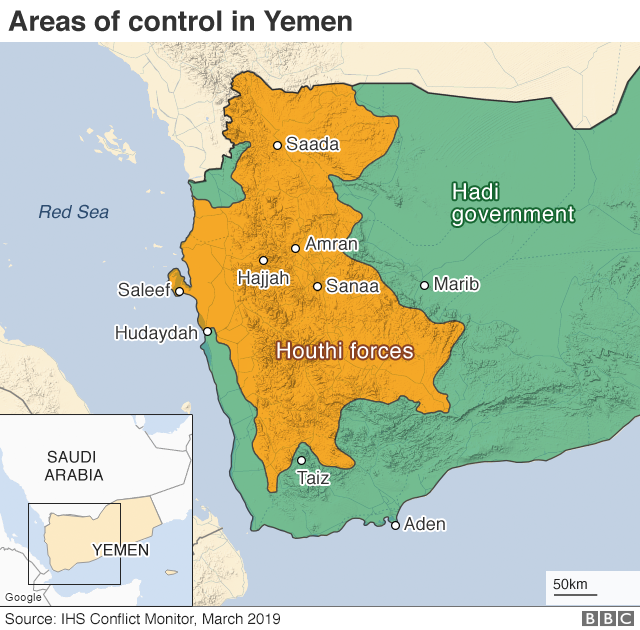

The Houthi movement, which champions Yemen’s Zaidi Shia Muslim minority and fought a series of rebellions against Saleh during the previous decade, took advantage of the new president’s weakness by taking control of their northern heartland of Saada province and neighbouring areas.

Disillusioned with the transition, many ordinary Yemenis – including Sunnis – supported the Houthis and in late 2014 and early 2015, the rebels took over Sanaa.

IA Saudi-led multinational coalition intervened in the conflict in Yemen in March 2015

IA Saudi-led multinational coalition intervened in the conflict in Yemen in March 2015

The Houthis and security forces loyal to Saleh – who is thought to have backed his erstwhile enemies in a bid to regain power – then attempted to take control of the entire country, forcing Mr Hadi to flee abroad in March 2015.

- Yemen conflict explained in 400 words

- How my country has changed

- Five clues (other than war) to guess my country

- The rise of Yemen’s Houthi rebels

Alarmed by the rise of a group they believed to be backed militarily by regional Shia power Iran, Saudi Arabia and eight other mostly Sunni Arab states began an air campaign aimed at restoring Mr Hadi’s government.

The coalition received logistical and intelligence support from the US, UK and France.

What’s happened since then?

At the start of the war Saudi officials forecast that the war would last only a few weeks. But four years of military stalemate have followed.

Coalition ground troops landed in the southern port city of Aden in August 2015 and helped drive the Houthis and their allies out of much of the south over the next few months. Mr Hadi’s government has established a temporary home in Aden, but it struggles to provide basic services and security and the president remains in exile.

The Houthis meanwhile have not been dislodged from Sanaa, and have been able to maintain a siege of the third city of Taiz and to fire ballistic missiles across the border with Saudi Arabia.

Militants from al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the local affiliate of the rival Islamic State group (IS) have taken advantage of the chaos by seizing territory in the south and carrying out deadly attacks, notably in Aden.

The launch of a ballistic missile towards Riyadh in November 2017 prompted the Saudi-led coalition to tighten its blockade of Yemen.

The coalition said it wanted to halt the smuggling of weapons to the rebels by Iran – an accusation Tehran denied – but the restrictions led to substantial increases in the prices of food and fuel, helping to push more people into food insecurity.

In June 2018, the coalition attempted to break the deadlock on the battlefield by launching a major offensive on the rebel-held Red Sea city of Hudaydah, whose port is the principal lifeline for almost two thirds of Yemen’s population.

UN officials warned that the toll in lives might be catastrophic if the port was damaged or blocked. But months passed before the warring parties could be persuaded to attend talks in Sweden to avert an all-out battle in Hudaydah.

- Ending Yemen’s never-ending war

- The girl with the strawberry ring

- The man who lost 27 relatives in an air strike

In December, government and Houthi representatives agreed to a ceasefire in Hudaydah city and port and promised to redeploy their forces by mid-January. But both sides have yet to start withdrawing, raising fears that the deal will collapse.

What’s been the human cost?

In short, Yemen is experiencing the world’s worst man-made humanitarian disaster.

The UN says at least 7,025 civilians have been killed and 11,140 injured in the fighting since March 2015, with 65% of the deaths attributed to Saudi-led coalition air strikes.

An international group tracking the civil war believes the death toll is far higher. The US-based Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project estimates that more than 67,650 civilians and combatants have been killed since January 2016, based on news reports of each incident of violence.

Thousands more civilians have died from preventable causes, including malnutrition, disease and poor health.

About 80% of the population – 24 million people – need humanitarian assistance and protection.

About 20 million need help securing food, including almost 10 million who the UN says are just a step away from famine. Almost 240,000 of those people are facing «catastrophic levels of hunger».

More than 3 million people – including 2 million children – are acutely malnourished, which makes them more vulnerable to disease. The charity Save the Children estimates that 85,000 children with severe acute malnutrition may have died between April 2015 and October 2018.

With only half of the country’s 3,500 medical facilities fully functioning, almost 20 million people lack access to adequate healthcare. And almost 18 million do not have enough clean water or access to adequate sanitation.

Consequently, medics have struggled to deal with the largest cholera outbreak ever recorded, which has resulted in more than 1.49 million suspected cases and 2,960 related deaths since April 2017.

- Yemen: Finding near-famine – and lots of food

- Yemen’s civilians pay price of blockade

- Witnessing Yemen’s desperate suffering

- The horrors of Yemen’s spiralling cholera crisis

The war has also displaced more than 3.3 million from their homes, including 685,000 who have fled fighting along the west coast since June 2018.

Why are there rifts among rebel and government forces?

The alliance between the Houthis and Mr Saleh collapsed in November 2017 following clashes over control of Sanaa’s biggest mosque that left dozens of people dead.

Houthi fighters launched an operation to take full control of the capital and on 4 December 2017 announced that Mr Saleh had been killed.

Only weeks later, infighting among pro-government forces erupted.

Separatists seeking independence for south Yemen, which was a separate country before unification with the north in 1990, formed an uneasy alliance with troops loyal to Mr Hadi in 2015 to stop the Houthis capturing Aden.

But in January 2018 the separatist movement known as the Southern Transitional Council (STC) accused the Hadi government of corruption and mismanagement, and demanded the removal of the prime minister.

Clashes erupted when separatist units attempted to seize government facilities and military bases in Aden by force.

The situation was made more complex by divisions within the Saudi-led coalition. Saudi Arabia reportedly backs Mr Hadi, who is based in Riyadh, while the United Arab Emirates is closely aligned with the separatists.

Calm was restored in Aden after a few weeks, but tensions between the two groups remain. In September, there were protests after separatist officials called for a peaceful popular uprising in the South.

Why should this matter for the rest of the world?

Suicide bombings claimed by the Islamic State group have killed dozens of people in Aden

Suicide bombings claimed by the Islamic State group have killed dozens of people in Aden

What happens in Yemen can greatly exacerbate regional tensions. It also worries the West because of the threat of attacks – such as from al-Qaeda or IS affiliates – emanating from the country as it becomes more unstable.

The conflict is also seen as part of a regional power struggle between Shia-ruled Iran and Sunni-ruled Saudi Arabia.

Gulf Arab states – backers of President Hadi – have accused Iran of bolstering the Houthis financially and militarily, though Iran has denied this.

Yemen is also strategically important because it sits on a strait linking the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aden, through which much of the world’s oil shipments pass.