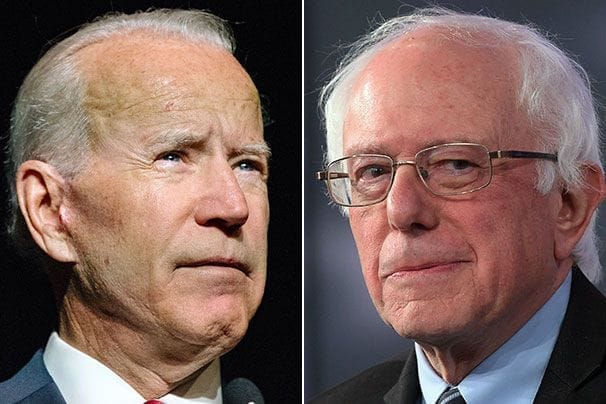

Democrats have to decide what to do with the two old men

As Democrats sort through their huge field of candidates, they must first decide about the two old men, Joe and Bernie.

The Sunshine Boys, Biden and Sanders. One’s a former vice president. The other’s the unlikely fellow who quickened so many pulses last time around. They appear together at the top of every poll. Together they have half, or more, of the early support.

It’s just name recognition, their opponents tell themselves — as if name recognition were not the whole point of the exercise at this stage. The quest for name recognition sends candidates down long roads through rolling Iowa fields from fish fry to Elks Lodge to campus student union. It propels them along winding, baffling New Hampshire byways from one living room to the next. They grovel for money and mug for YouTube. Why? To get their names out there. They want what Biden and Sanders already have, because people won’t vote for you if they haven’t heard of you.

But here’s the thing. It’s not just name recognition. Biden and Sanders connect with their supporters in ways that could prove quite sticky. They are not a couple of haircuts in standard-issue blue suits. They aren’t riding high because they seem “presidential,” whatever that means in the age of President Trump. An entire generation of would-be presidents from Central Casting has gone by the wayside, but these two originals remain. The schmoozer and the loner. The self-described “gaffe machine” and the permanent party of one.

As younger men, they could not have been more different. Biden’s politics came from the gut. He played it by feel. He liked to be part of the action, and sometimes that lack of reflection took him places a more circumspect politician would not go. Already, critics of Biden are turning the lens of 2020 on his choices from ages past: his opposition to court-ordered busing to desegregate schools in the 1970s; his handling of testimony as Senate Judiciary Committee chairman from law professor Anita Hill during the Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Clarence Thomas in 1991; his eulogy for white supremacist and longtime senator Strom Thurmond in 2003. Even now, he blurts without calculating.

Even Biden’s enemies, if he genuinely has any, would probably not argue that he is defined by racism or sexism. But many notes have been struck in his improvised career, which has been one long jam session complete with sampling, riffing and the tragic experience of the blues.

For Sanders, on the other hand, politics is cerebral. He has a set of ideas, and they light his every step. He entered the business as a civil rights organizer in the 1960s and carried the left-wing flame thenceforth. As mayor of small-town Burlington, Vt., he was perhaps the most prominent socialist of the Reagan 1980s. When he entered Congress as a representative in 1991, he often allied with the Democrats but refused to join their ranks, lest he sully his independence. His principal problem is with Democratic women who hold him partially responsible for the fate of Hillary Clinton, whose Wall Street ties he tirelessly denounced in 2016. But he can answer that he would have been just as righteously unforgiving of any male candidate’s compromises.

With age, their differences have softened into superannuated similarity. What stands out now is their authenticity, their apparent lack of self-consciousness. With his rumpled clothes and mad-professor hair, Sanders is perhaps the least picture-perfect candidate in the field, and his look seems to say, if you don’t like it, tough. Biden’s look said something similar in the 1990s, after he clearly endured a series of hair transplants. Yet Biden preferred this candor to the weak deception of a toupee, weave or comb-over.

Few politicians remain in the fray long enough for their flaws to ripen into quirks, much less for their quirks to become selling points. Biden recognized the milestone in his memoir published last year. “My reputation as a ‘gaffe machine’ was no longer looking like a weakness,” he observed.

The younger rivals of the septuagenarians will need to do more than catalogue those flaws and quirks in their efforts to bring Biden and Sanders down to earth. A gold-watch strategy is required — a positive message of generational change that acknowledges their contributions even as it shoulders them into retirement.

Such a strategy demands real talent from a candidate, a combination of youthful charisma and deep understanding of historical currents and emerging challenges. An agent of generational change must explain the past, diagnose the present, paint the future and embody renewed confidence. If such a candidate exists in this bunch, we’ll know soon enough. If not, don’t be surprised if Democrats decide to let a familiar warhorse carry the party’s banner into battle one more time.