What’s Behind China’s Growing Push into Central America?

Growing tensions with Washington, and the post-COVID landscape, seem to provide an open door for Beijing.

For nearly 60 years, the preeminent Asian power in Central America was not the People’s Republic of China, but Taiwan. Yet in rapid succession starting in 2017, Panama, the Dominican Republic and El Salvador surprised many by switching their diplomatic recognition to Beijing, joining Costa Rica, which had done so in 2007. While four Central American nations remain today within Taiwan’s shrinking circle of international supporters – Belize, Guatemala, Honduras and, curiously, Nicaragua – it is fair to wonder whether those alliances, too, may now be in danger.

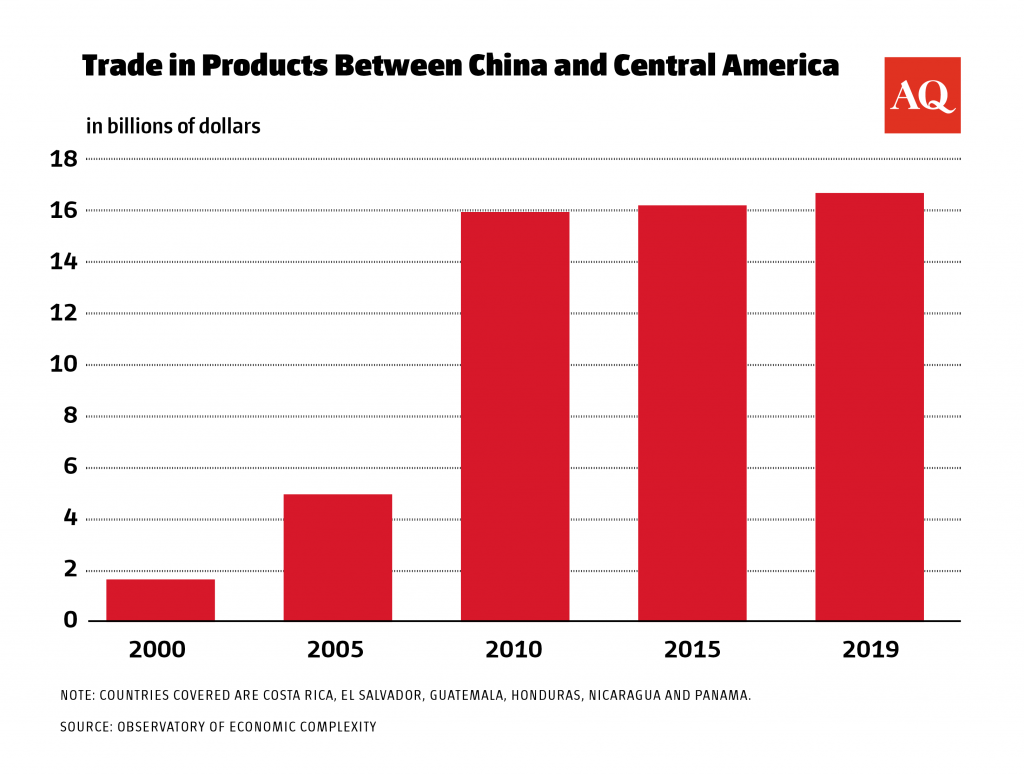

Today, China’s methodical push for a bigger foothold in Central America is no longer surprising anyone. While Beijing’s relationships in the isthmus are not yet as deep as those in South America, the Chinese government clearly sees an opportunity to expand its presence for both commercial and geopolitical reasons. China hopes to turn Panama into another axis of its “Belt and Road Initiative” for the Americas and gain preferential access to the only real strategic asset in the area: the interoceanic canal. Meanwhile, Central American countries’ acute need to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as some governments’ growing desire for a “more accommodating” alternate partner to the United States, may constitute a favorable context that pushes the isthmus even further into Beijing’s embrace in coming years.

For many years, the growing Chinese presence did seem to fly somewhat under the radar of the United States and other observers. Even Costa Rica’s 2007 switch of diplomatic status to Beijing did not seem to set off many alarm bells at the time. After all, Costa Rica is a trusted U.S. ally and no other Central American country immediately followed suit. Furthermore, the initial results of Beijing’s foray were scant and problematic, a fact that successive Costa Rican governments did nothing to hide. Issues arose with Beijing-led projects like the enhanced road to the Caribbean port city of Limón, the cancellation of a plan to build an oil refinery, the failed attempts of China to win infrastructure projects, and the inability (or unwillingness) of Costa Rican authorities and entrepreneurs to attract more tourists from China without weakening migration restrictions. Not even the existence of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the two countries since 2011, nor the “strategic relationship” which China and Costa Rica vowed to develop after 2015, was sufficient to generate significant concern from Washington.

As president of Costa Rica from 2014-18, I tried to enhance our country’s relationship with China for three main reasons: 1) To further our efforts to develop public infrastructure (roads, ports and bridges in particular) 2) To diversify our export markets using the binational FTA provisions fully; and 3) To consolidate a telecommunications platform whose bases had already been established by previous administrations. During my term only once was I told, towards the end of my mandate and indirectly, that U.S. trade authorities could eventually object to the installment of several donated Chinese scanners in the ports of Costa Rica.

But after the triple diplomatic defections in 2017 and 2018, the Trump administration changed course, and identified the Chinese presence in Central America – and Latin America as a whole – as an issue of grave significance. Throughout 2018 both President Trump and then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo repeatedly expressed their aversion to Chinese activities in Latin America (particularly its diplomatic and economic support for the Maduro regime in Venezuela). They also warned against deals that were “too good to be true” and accused Beijing of carrying out “nefarious” actions in the region. The Chinese retaliated, calling the US criticism “slanderous,” “irresponsible” and “despicable.” After visiting Panama in October 2018, Pompeo said he had warned the local authorities against Chinese “predatory economic activities.”

Biden is also on the alert

Today, the Biden administration has so far maintained much of the spirit, if not the rhetoric, of opposing Chinese activities in Latin America. But the ground is clearly shifting due to the pandemic. China has moved fast to display its so-called “vaccine diplomacy” in El Salvador and in the Caribbean, while trying to resume business as usual in terms of its economic and diplomatic relationships elsewhere. The United States has so far announced its decision to steer large quantities of vaccines to the region but is delivering them only gradually. Biden’s government has also focused on yet another intense migratory wave from towards the U.S., which has dictated the tone and substance of its relationships with Central America’s Northern Triangle governments, sometimes with contentious overtones.

Partly as a result, Central America seems particularly fertile ground for Chinese expansion. The region is currently divided between one dictatorial regime (Nicaragua), two seriously compromised states because of the activities of transnational organized crime (Guatemala and Honduras), one nation on the verge of becoming yet another example of populist, autocratic rule (El Salvador), and three generally stable countries (Belize, Costa Rica and Panama) suffering from the financial and political fallout of long-term systemic dysfunctions exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A list of U.S. concerns about Chinese expansion in the region probably will begin with Panama. Linked by 21 major infrastructure projects like ports, telecommunications, rapid trains and roads (plus the enhancement of the already saturated Tocumen airport) Panama could soon become one of China’s most important outposts in the Western Hemisphere. Meanwhile, the president of El Salvador has already hinted, seconded by his colleague from Honduras (who has been repeatedly accused of being associated with a narcotrafficking network) that they could seek the support of new allies who are more “understanding” than the U.S. on issues pertaining to democratic principles and human rights practices.

Faced with this changing reality, China has often been content to sit quietly and enjoy the benefits. In fact, while the Russians have been actively providing advanced military logistic support and counsel to Nicaragua and Venezuela for more than a decade, the Chinese have been particularly muted in advancing any military or security related deals in the region except for funds to build a police academy in Costa Rica, and the donation of anti-riot equipment to Panama. Furthermore, they do not seem interested in bringing in too much public attention to their business deals in Central America. This is true of their powerful telecom corporation Huawei, which successfully competes in all the national markets, but especially in Costa Rica and Belize. In these two countries Huawei is not monopolistic, but it is certainly a very competitive player. For example, it controls 37% of the cellular market of Costa Rica. But most importantly, Huawei is ahead of its technological rivals in preparing for the 5G transition. While the resolution of this issue has been delayed by U.S. pressures and debates between different local economic sectors, it will inevitably gain a high profile in the coming months as Costa Rica nears the election of a new president in February 2022 and moves to regain its trade and tourism competitiveness after the pandemic.

A push into the military sphere?

A big question lingers: Could China take advantage of the current situation in Central America to accelerate its involvement beyond economic and trade parameters?

In the view of Lt. General Andrew Croft, Deputy Military Commander of the U.S. Southern Command, it already has done so. Mostly because of what he calls “strategic ownership.” In his view, there is no such thing as an economic/political divide in Chinese activities. Given the peculiar nature of Chinese business, which is significantly controlled by the state, the fact is that China simultaneously uses its so called “private” companies to advance political objectives. Chinese opportunism is, in this regard, a given that will use any critical development to enhance its influence. Such was the case with the provision of COVID-19 vaccines, the sustained solidarity of China with Venezuela and its more recent announcement of the future construction of a new port in El Salvador. China has also provided diplomatic sympathy to Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele after receiving justified criticisms from the Biden administration over his increasingly autocratic behavior.

It is unlikely that China will attempt to formalize agreements or carry out military exercises or any other activities that could be seen as a direct threat to the U.S. in the Caribbean Basin, as Russia has. Yet, joint military exercises have already been announced in Argentina as part of their 2015 understanding, which includes the possibility of China building military space installations in that country. Would China be willing to risk a major confrontation with the U.S. and emulate the Russians in Venezuela or eventually, in Nicaragua? The Ortega regime, a dictatorship, seems determined not to abandon power through elections anytime soon. What if Nicaragua were to break away from its Taiwan relationship and rush to Beijing to counteract further and more serious U.S. government sanctions resulting from Ortega’s increasingly repressive behavior?

What’s clear is that several Central American governments see Chinese engagement as an opportunity to “build back better” after the pandemic. And this circumstance, in a region that has of late been devastated by COVID-19, two major hurricanes (likely to happen again as the region continues to be gravely affected by climate change), and is suffering from profound, structural democratic deficits, could put strains in the balance of power in a highly sensitive area for the United States. Clearly, Washington continues to enjoy a solid geopolitical predominance in Central America that the Chinese cannot match in the short term. Yet, the challenge is not small nor the outlook optimistic, unless Central America is capable to significantly increase its human development and overcome its deep democratic failings. This is one of the region’s most pressing trials.

__

Luis Guillermo Solís is the interim director at the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center at Florida International University and the former President of Costa Rica