‘Eleanor Marx: A Life,’ by Rachel Holmes

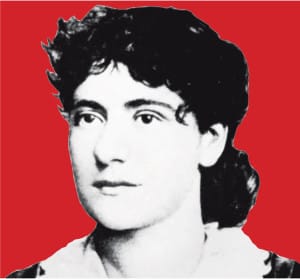

Eleanor Marx Credit Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

Three women possessed of extraordinary political talent loved men who were unworthy of them: Rosa Luxemburg, Emma Goldman and Eleanor Marx. The first two survived these debilitating attachments, the third did not. At the age of 43, upon learning that her common law husband of 14 years had secretly married a 22-year-old actress, Eleanor took poison and died. Had her father, Karl Marx, been alive he would have been not only distressed by her death but, I think, dismayed that a daughter of his could not surmount this level of betrayal, for the sake of international socialism if nothing else.

Karl and Jenny Marx were married in 1843. At the time, Marx was already a law student turned radical journalist, his writings and his political activity contributing to the turbulent times that would soon explode into the 1848 revolutions that shook but did not topple the monarchies of Europe. As his work was forever drawing the attention of hostile governments everywhere, Marx and his wife were often on the move, expelled from or fleeing one country or another — Germany, France, Belgium — usually a minute before Karl was about to be arrested.

After the publication of “The Communist Manifesto” in 1848, life on the European continent became truly perilous for the Marxes, and the following year they moved to London. There they lived, for the rest of their lives in a combined state of immigrant want and bohemian intellectualism, continually bailed out by Marx’s devoted collaborator, the wealthy Friedrich Engels. As a grown woman, Eleanor, bent on indicting capitalism, wrote that in London the family endured “years of horrible poverty, of bitter suffering — such suffering as can only be known to the penniless stranger in a strange land.” This was true, but it was also true that together the family read Shakespeare, took long walks, listened to music, had Sunday open houses to which every revolutionary visitor or exile in London came, and talked politics nonstop. For better and for worse, it was a life of physical hardship made vibrant by the sense of mission that flowed from the Great Man who sat writing “Das Kapital” at the kitchen table for some 12 years.

Between 1844 and 1855, Jenny Marx bore seven children, only three of whom lived into adulthood: Jennychen, Laura and Eleanor. All three daughters grew up “living and breathing historical materialism,” as Rachel Holmes tells us in her new biography, “Eleanor Marx,” but none breathed it in more deeply than this youngest child. When she was a teenager her mother referred to her as “eine Politikerin von top to bottom”; to which her father added that his other two children were like him, but Eleanor was him. And indeed, while the two elder sisters married “likable, liberal Bluebeards who lassoed their desire with babies,” Eleanor grew up to become a major player in the rise of British socialism, living her life in an unbroken extension of the one into which she had been born.

She was a lovely girl — her eyes dark and expressive, her hair a mop of black curls — and from earliest childhood smart, passionate, argumentative. Although in love with literature and languages, music and theater, it was always radical politics that set her on fire. Socialism ran in her veins and glowed on her skin. Before she was 20 she was arguing that the English worker movement was at a standstill, something had to be done, and she was aching to do it.

The first British socialist organization (called the Democratic Federation) was formed in 1881. When it was re-formed in 1884 as the Social Democratic Federation, Eleanor was among its initiating members. Until her death 17 years later, she lectured and wrote on behalf of socialism; helped organize strikes, rallies, election campaigns; and played a role in the internecine struggles that went on in every socialist group to which she belonged. Often she was perceived as a highhanded steamroller who acted as though socialism was her private property (after all, she was her father’s daughter, wasn’t she?), but just as often it was clear that the oppressed of the earth were very real to her — “Sometimes I wonder how one can go on living with all this suffering around” — and her honest belief in the virtue of socialism ran deep. In a letter she wrote in 1885, while arranging for a Christmas festival for children, she said, “We cannot too soon make children understand that Socialism means happiness.”

When she was 27 years old, Eleanor met Edward Aveling — freethinker, biology teacher, disciple of Darwin — in the British Museum’s Reading Room. They began living together, and she drew him into her innermost political circles. Soon they were a power couple, with Aveling on the podium as often as Eleanor. It was her extraordinary energy that almost invariably led the intellectual way, but they were, in fact, a remarkably successful team. If it was she who dreamed up subject after subject for them to speak, write or organize around, Aveling was always ready to fall in with her suggestions, and he reveled in all that made Eleanor worthwhile. Her intellectual passion, her political high-mindedness, her steadfast devotion to the Cause — for all this he loved her. Yet he told her that he couldn’t marry her because he was already married and lied that he couldn’t get a divorce. (He later concealed the fact of his wife’s death.)

Aveling was considered an excellent speaker and a reliable socialist, but he was also seen — and this quite early — as a man of little moral worth. Not only was he an open womanizer, but whenever he took financial control of a project (as he often did) no one could balance the books. He hungered for good clothes, expensive restaurants, cabs and theater tickets, and was indifferent as to how those desires were satisfied. “The best was good enough for him,” sneered one comrade, “at no matter whose expense.”

The person at whose expense Aveling generally made himself comfortable was, of course, Eleanor. Besotted throughout her time with him, she was yet often miserable. Aveling was selfish, nasty, petty, and three times out of five not there when she needed him; a hypochondriac of some dimension, he was forever going off to take “the cure” somewhere (really to rendezvous with other women), leaving Eleanor alone for weeks on end. As the years went on, the discrepancy between a crowded public life and a lonely personal one weighed ever more heavily on her.

Yet she couldn’t give him up. Why? Let me hazard a guess.

Like Rosa Luxemburg and Emma Goldman before her, Eleanor suffered the burden of occupying a singular position, that of a powerful woman in an overwhelmingly male world where, to put it bluntly, she was experienced as a freak: the denatured brilliant exception who is neither fish nor fowl. Each of these women was more alone than any of their male comrades could ever be. The men whom they loved, insufficient as they were — Rosa’s Leo Jogiches was a sociopath, Emma’s Ben Reitman a satyr and Aveling, an exploiter of the first order — were genuinely respectful of the brilliance of mind and spirit with which these valiant women were endowed. Mad, vain, selfish as the men were, in their company the women felt more than cherished or admired, they felt known. For this, they could not easily free themselves of the humiliations inherent in relationships that in all instances were degrading, and in one fatal.

Need anything more be said to justify 200 years of struggle to establish women on something that resembles a level playing field?

Rachel Holmes’s biography of Eleanor Marx is probably more hagiographic than it should be — its opening line is “Eleanor Marx changed the world” — but it captures vividly the drama of a woman with a hunger for the world who did her damnedest to live life on the largest terms possible, and to a very considerable degree succeeded.

ELEANOR MARX

A Life

By Rachel Holmes

Illustrated. 508 pp. Bloomsbury Press. $35.

Vivian Gornick’s latest memoir, “The Odd Woman and the City,” will be published in May.